The oral history of Anti-Flag: "We were machete-ing our way through failure"

Punk is a genre full of people who are always yelling, but over the past 30 years, Anti-Flag might have been yelling the most. It’s frequently between songs onstage, about the sorry state of the world — wars for oil, police brutality, a system rigged against its people. Truth is, Anti-Flag have had plenty of reasons to be losing their minds in public.

Through all the yelling, the quartet have been preaching peace, unity and power to the people: from DIY venues in their native Pittsburgh, from club tours with comrades like Rise Against and Against Me!, from war-torn nations overseas. They’ve played punk institutions like Warped Tour and Fest, and also Coachella. A punk band in the tradition of the Clash, they’ve rallied for leftist concepts within an industry often hostile to them, and done a damn good job of it. Whether making noise is in vogue or not, Anti-Flag are always loud.

Read more: 23 of the most exciting rising artists to watch in 2023

In 2023, Anti-Flag celebrate their 30th anniversary. They’re also sharing their 13th studio album, Lies They Tell Our Children, out today on Spinefarm Records. It’s a brazen, righteous LP that proves Anti-Flag’s dedication hasn’t wavered. The album features eight collaborations, ranging from punk legends (Minor Threat/Bad Religion guitarist Brian Baker) to some of the genre’s most exciting young voices (Pinkshift singer Ashrita Kumar).

Anti-Flag really mean it, and they’ve been that way for three decades; it’s no surprise they’ve been to the brink of implosion. They’ve been nearly obliterated by rickety tour vans and bloodthirsty red state mobs. They’ve gambled at the major-label punk-rock poker table and come out winners. Chatting with the band from their Pittsburgh studio a few days before Christmas, enthusiasm is palpable for what year 30 holds.

To mark the occasion, we’ve compiled Anti-Flag’s oral history, as told by the band, and the company they’ve kept over the decades. Long before alt-culture icons like Tom Morello and Rick Rubin entered their orbit, the Anti-Flag story begins in the early ‘90s, in a blue-collar city America had left behind…

“Machete-ing Our Way Through Failure”

JUSTIN SANE (vocalist-guitarist, Anti-Flag): Every community has an imprint on the art that comes out of it.

CHRIS #2 (vocalist-bassist, Anti-Flag): There was this longing for the golden era of Pittsburgh, the boom of the steel industry. It was the gateway to the west for so long. All of us grew up with that being gone.

JUSTIN SANE: Pittsburgh wasn’t a progressive place in almost any way, except for labor. Labor history and Pittsburgh go hand in hand.

CHRIS #2: There was a mill in Monaca, Pennsylvania, about 30 minutes outside of Pittsburgh, where my aunt and uncle lived, and I would spend summers with them. My uncle was a janitor. The mill was shut down in the ‘80s, and it had a major effect on their family — he was the breadwinner. Now, with the perspective of age, what was interesting to me was talking to him about the labor movements. There wasn’t a hierarchy. He was a millworker, even though he was a janitor. He had this solidarity with the rest of the millworkers, which was powerful.

PAT THETIC (drummer, Anti-Flag): In the ‘70s, the steel industry in Pittsburgh collapsed. It wasn’t until the medical industry came in during the early 2000s that the economy started to work again. We grew up in the bottom of that before it started to lift itself out.

JUSTIN SANE: For a lot of our friends, a ticket out was to join the Army. That was it.

The first Gulf War happened [in 1990], and all of a sudden, there’s flags everywhere. We’re this community that’s been left behind by our government, by society, and now you want us to go overseas and fight, kill and die for oil? We were old enough to have had a couple friends join the military for a chance to get out of town. All of a sudden, they’re over there, and they don’t want to be there. That was where the band name came from. Patriotism was being distorted into nationalism. And that was being used to manipulate people.

CHRIS #2: When Pat and Justin started the band, they were teenagers, and when you’re a teenager in Pittsburgh, the military would come to your high school: “Do you want to see the world? Sign here. Do you want money for college? Sign here.” Thankfully, [Pat and Justin] had the wherewithal to resist them and say…

PAT THETIC: “We believe playing in a punk-rock band is a better route,” ha ha ha.

JUSTIN SANE: Certainly not economically, certainly not in our relationships. But we didn’t die when we were 18. Growing up the way we grew up, punk was perfect. I was a poor kid who didn’t have access to anything, like even a winter coat sometimes.

CHRIS #2: He’s the youngest of nine because they were Catholic, and that’s what Catholics did back then. They made a lot of fuckin’ babies.

JUSTIN SANE: Even though my parents worked really hard, I didn’t wanna bother my parents because I knew they didn’t have a lot of money. I would go to school with this shitty spring jacket and freeze to death. Then there’s this music where you don’t have to have the latest thing, you don’t have to be into the trends. I have this shitty drum set I scraped from different people. I have this crappy guitar…

CHRIS #2: In 1993, [bassist] Andy [Flag], Justin and Pat started Anti-Flag as we know it. It takes another three years to make the first record, Die for the Government. And it takes another two years before it’s the four of us… Head, you saw Anti-Flag before I did… Did you see them first, or did you play with them first?

CHRIS HEAD (Anti-Flag guitarist): So I worked at Little Caesars, and one of Anti-Flag’s friends, Punk Rock Anne, worked there at the time, and she talked me into seeing Anti-Flag.

JUSTIN SANE: Well, you went to see Fifteen. We were opening… We were so disorganized. We didn’t know what we were doing. We came to the show, and Fifteen was already playing. The promoter was screaming at us. I thought you went to a show late! We were like, “Well, can we still play?”

CHRIS HEAD: We watched Fifteen, I was with my girlfriend at the time, and we decided, “We’ll stick around and watch Anti-Flag.” Justin was talking with this sort of British [accent], “Fuck youuu.” My girlfriend was like, “Let’s go.” I was like, “I don’t wanna go. This guy is singling out people in the audience!”

PAT THETIC: Head started out playing bass; we were like, “This dude’s cool. We need a bass player…” Then we were like, “Head, you sort of suck at bass,” and he’s like, “Yeah, I don’t really want to play bass. I want to play guitar.” We’re like, “So I guess we’ll just become a four-piece. You can play guitar, and we can find another bass player…”

CHRIS #2: In my false confidence state of boxed wine drinking, I was like, “Fuck man, I can do better than that!”

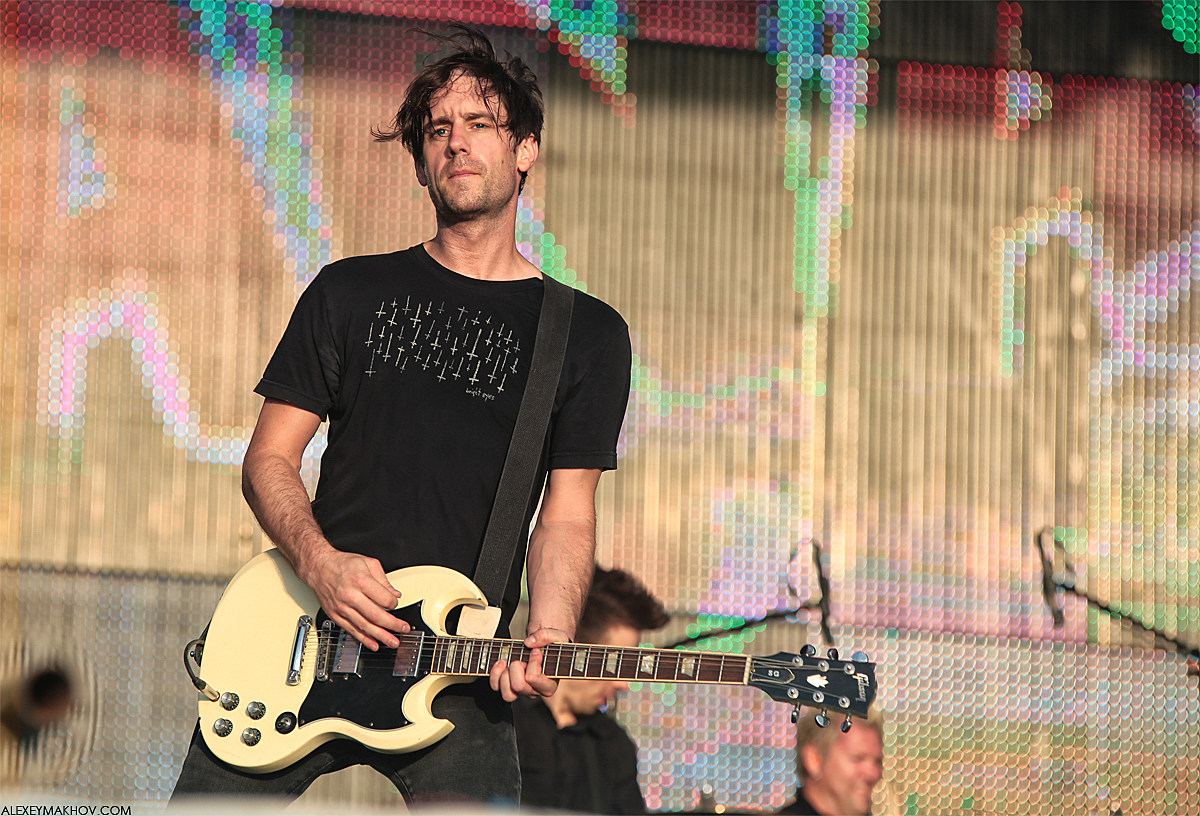

[Photo by Alexey Makhov]

PAT THETIC: I didn’t know anything about #2. I just knew that Justin was scheming behind my back to get him in the band. That’s why I was sort of grumpy with him: This kid’s drunk all the time. He’s just a mess. I gave him the name #2: He introduced himself and said, “I’m Chris,” and I said, “We already have one Chris in the band, you’ll be #2.”

CHRIS #2: I didn’t know they were straight edge. I mean, they had songs like “Drink Drank Punk.” I thought that meant, “We’re punk, and we drink!” I was 16 years old!

JUSTIN SANE: When we started the band, I had this persona… it came from Johnny Rotten… when you’re onstage, you wanna be the punkest motherfucker alive. I would spit on people. I swore every three words. That’s what everyone in the Pittsburgh punk scene did: Who can be more punk than the next person?

TIM MCILRATH (vocalist-guitarist, Rise Against): The scene in Pittsburgh was really tight knit, organized, DIY, everybody in it together. It seemed like they had less of the tribalism that some of the bigger cities have.

CHRIS #2: Talking about Pittsburgh, there were no references. No one had ever made it. It wasn’t like living in New York or LA where you could say, “Oh, here’s this band. This was the path they took. It might be a little overgrown, but you can still see through it. Let’s follow it.” We were literally machete-ing our way through failure.

JUSTIN SANE: As [Chris Head and Chris #2] came into the band, that drive just continued. The drive to do it — there was nothing else in our lives. Pat slept on somebody’s basement floor, I was at my parents’ house. We did whatever we had to do for the band to keep creating.

“When Power Structures Start to Fear Artists…”

CHRIS #2: In Pittsburgh, the band was starting to play to more people. Seven hundred, sometimes 1,000 people would come to the local shows. It commanded our attention and respect. We never took [the shows] for granted. We always saw them as opportunities to grow the community around the band, the ideology and the politics. All four of us at that moment in 1998 collectively decided, “OK, doors are starting to open. Let’s walk through them with confidence.”

JUSTIN SANE: We were like, “Fuck, I want to have a band of friends and drive around the country.”

SHANE TOLD (vocalist, Silverstein): I saw Anti-Flag play right after Chris #2 joined. I remember this vivid moment at the Toronto Opera House, this absolute institution of a venue. I’m 17 at the time, and Chris was about a year older than me, up there on tour, playing an 800-cap venue. They had some kind of run-in with the police that day, and I remember Justin going into this speech about what happened and the cops and how fucked up it was, and all of a sudden, it’s like, “This song’s called ‘Fuck Police Brutality’!” Up to that point, I’d never seen such a visceral live moment with so much emotion behind it. There was such unity amongst the crowd. Everyone was there for the same reason.

CHRIS #2: We did a U.S. tour with the Dropkick Murphys in the spring of 1999. They had a foot in the skinhead, pro-American… almost a working-class type of solidarity, but still based in a bit of nationalism…

PAT THETIC: Dropkick fans tended to be people who were more aggressive than the people who were interested in Anti-Flag. It was a volatile mix.

CHRIS #2: We would have a show in Denver that was really positive. We drive south to Oklahoma City, and Anti-Flag’s getting beer bottled the entire show. It’s a really painful, arduous tour, about five weeks long. We get to Texas the last week, and the show is just a nightmare. These men [in the crowd] would look for anyone in an Anti-Flag shirt, grab them and punch them. It’s happening during the show, and we don’t play if there’s a fight. We’re stopping every two seconds. We’re trying to get security to throw them out, but we’re in Texas, so the security sees us like, “Fuck you!” We get off the stage, and Pat says something like, “Fuck this, these people are idiots.” The Dropkick Murphys hear that, they think we’re insulting their fans, they get angry with us. We kind of squashed that beef, but the next day, we show up, and they’ve hung an American flag as the backdrop — right side up — ask us to play our show in front of it, and we refuse. We bailed on the tour. It was financially crippling.

On that drive home, not only are we broke, not only are we tail between our legs because the bullies beat us up… We used to tour in a U-Haul box truck with six bunks built in. Justin gets carbon monoxide poisoning in the truck because there’s a leak going right into his bunk. He’s in the hospital nearly dead, and Rage Against the Machine calls us and asks us to go on tour and changes our life forever.

JUSTIN SANE: Tom Morello took a liking to us.

TOM MORELLO (guitarist, Rage Against the Machine): I was familiar with their music and loved their uncompromising, fiery punk politics. That was all well and good. The problem was you couldn’t find Anti-Flag. There was no phone number. I looked at every cassette and album, yellow pages and white pages in Pittsburgh… At some point, through some circuitous route, I was able to contact them.

[Photo by Jen Palmer]

CHRIS #2: When we’re finally able to get Justin out of the hospital and get back onstage, the first show with Rage Against the Machine is in Philadelphia. It’s protested by the Philadelphia Police Department because Rage Against the Machine supported Mumia Abu-Jamal, a political prisoner Anti-Flag had done activist actions for.

JUSTIN SANE: It was just across the state in Philly, so we were aware of it.

CHRIS #2: But our activist actions were in a club with 200 people. And their activist action was in an arena. We’re in the hotel before the show, all four of us in one room, and on the television is the chief of police saying, “Don’t let your kids go to this show. Rage Against the Machine support a cop-killer, Mumia Abu-Jamal.” We look at each other like, “A band has disrupted so far that they’re going to the local news? We’ve got a lot of work to do.”

JUSTIN SANE: That show was at the Philadelphia Spectrum. I’d never been to an arena concert. My first arena concert was playing an arena concert. You pull up, and the cops have police cars circled, surrounding the arena.

CHRIS #2: They were protesting the show. They had to open up the line to let us in. We showed up in the same box truck that almost killed Justin a week prior.

I remember tuning my bass guitar, and I turn around — my tuner’s on the floor facing the back of the stage — and the corner of the arena is sold out. There’s more people watching my back than I’ve ever played to before.

TOM MORELLO: That night, I remember there was a particularly fiery speech onstage…

CHRIS #2: Zack de la Rocha had a genius line that was something like, “They say we support a cop-killer. We don’t support any killers. Especially killer cops.” And then boom, they go into a song like “Killing in the Name.” Like fuck me, man, that’s it. There was so much explaining we had to do with our shows because we were really adamant that everyone understood what we were trying to say. And to see a band that had so much confidence, they only spoke when it was truly necessary…

PAT THETIC: When power structures start to fear artists, that’s a good thing.

TOM MORELLO: Two things struck me when I got to watch them perform on a nightly basis. One was how skinny and black their clothes were. And two was their intense, authentic commitment to changing the world via a two-and-a-half minute song.

CHRIS #2: Later on, Tom [Morello] was like, “Don’t chase. If you hear a song and want to write something that sounds like that, you’re already too late.” So, the reference became just be true to yourself, and that will resonate. Thankfully he told us that because later on when we were signing to bigger record labels and making bigger decisions, it’s very easy for bands to look around and say, “Well, they’re having success, and I’m gonna follow that.”

FAT MIKE (vocalist-bassist, NOFX; founder, Fat Wreck Chords): I heard that song “Gonna die, gonna die, gonna die for the government,” and I liked it… I think I tried to steal them from [their label] New Red Archives.

CHRIS #2: Fat Mike became aware of Anti-Flag because of Pete [Steinkopf] from the Bouncing Souls, I believe.

JUSTIN SANE: Fat Mike called, and he was like, “Have you thought about your next record?” I was like, “Yeah, we’ve been recording it ourselves. We’re not sure how we’re gonna release it.” And he was like, “Well, I wanna put it out.” Which I thought was great because everybody kept saying Fat Wreck Chords was a great record label, that it would open a lot of doors, we would have full control over what we were doing, that distribution would improve dramatically from where we were. We were already recording in our home studio…

PAT THETIC: By “home studio,” you mean a guy’s abandoned house…

CHRIS #2: A New Kind of Army, the second Anti-Flag record, was recorded in four or five places, any space we could find that had enough room to set some microphones up: We recorded in Justin’s… we called it The Shack. It was above his parents’ garage. There was also an empty warehouse that we found and a person’s house that they were yet to move into.

JUSTIN SANE: I could tell Fat Mike was disappointed we had already started to make the record. He never said this, but looking back from what I know now, I’m sure he wanted us to go to San Francisco, record in a good studio there, and he would probably produce it. He had cultivated a sound on Fat Wreck Chords where the bands sounded really professional. I’m sure he was thinking, “This band needs work.”

[Photo by Alexey Makhov]

FAT MIKE: Well, it’s not as good as their first album. I think that’s popular belief.

JUSTIN SANE: We sent him our record, and he was like, “It’s not clean enough for Fat Wreck Chords. I have a subsidiary record label I would like to put it out on.” On Fat, there were bands we could identify with, like Swingin’ Utters, Good Riddance, Propagandhi. These bands had a social message. The subsidiary was called Honest Don’s, and it had more of a joke flavor to it. When we said no, we completely blew Mike’s mind because he offered 60 or 80 grand for the record. At the time, that was just an astronomical amount of money. I mean, bands today aren’t getting $80,000 to make a record.

The irony of the whole thing is we signed with Mike for the next record, which he agreed to put out on Fat, but A New Kind of Army sold 100,000 records much faster than the record we put out on Fat [2001’s Underground Network]. Even Mike later was like, “Wow, I really fucked up on that one.”

FAT MIKE: They gave me Underground Network, which is an amazing album. So is [2003’s] Terror State. I think I got them at the right time.

“To Be in a Band Called Anti-Flag on Sept. 12 Was a Hard Thing to Do”

CHRIS #2: There ain’t no war without warriors, you know? If you can create the solidarity movements, these rallying cries allow people to feel empowered.

JUSTIN SANE: We had a lot of friends in New York. Head’s dad was standing right in front of the second tower when it got hit.

PAT THETIC: Head’s father was going to a meeting… Head had to go pick him up.

CHRIS #2: Head’s parents told him to tell us to change the band’s name…

CHRIS HEAD: I mean, they weren’t the only ones. I had cousins, all kinds of people calling me: “Time for you to rethink that.”

CHRIS #2: To be in a band called Anti-Flag on Sept. 12 was a hard thing to do.

JUSTIN SANE: 9/11 was a horrible tragedy. Not just as Americans — but as human beings — we reacted to it, and it was horrible. But right away, we had concerns with what the Bush administration was going to do in the aftermath of 9/11. The idea that you’re going to invade an entire country because of one bad guy there, that smelled of imperialism, and then George W. Bush gave his “Axis of Evil” speech where he was talking about North Korea, Iraq, Iran… He’s doing what every imperialist politician has done throughout history: using a tragedy, and turning it into an opportunity to enrich himself and his friends.

CHRIS #2: That moment of “Oh fuck, what do we do?” was three days long. We were back in the studio, and we wrote a song called “911 For Peace.”

JUSTIN SANE: We had been in the studio for a few days, and then 9/11 happened.

CHRIS #2: So we took a few days off, and then Justin came in and said, “I have this song.” We read the “911 For Peace” lyrics, we talked about them, and then the four of us said, “When people ask where Anti-Flag stands, now we have this piece of art to present and say, ‘We’re on the side of people; we’re not on the side of the gun. We don’t believe dropping bombs on people’s heads is the solution to this problem.’”

JUSTIN SANE: We were really on a fuckin’ island. Even my own mother, who was the biggest peace advocate I ever knew, I think for about three months she was totally on board, like, “Yeah, let’s go.” But when I saw that, I realized the amount of fear 9/11 had created in people. My mother was scared. You could see it on her face. I realized, “Wow, we’re really gonna be alone on this.” But as a band, there was never any question.

CHRIS #2: People were waiting for clarity. And that’s OK. It was an unprecedented moment, and it took time.

JUSTIN SANE: We didn’t go back on tour [in 2001]…

PAT THETIC: But we did book our own show. We said, “What can we control?” So we booked our own show [at Mr. Roboto Project, a Pittsburgh-area DIY venue] and put 500 people in a room.

CHRIS #2: That was our first performance in a post-9/11 world [on Dec. 1, 2001].

JUSTIN SANE: And our broken gun logo, which we call the Gunstar, came out of that. We printed shirts for the show and we gave everybody a shirt, so everybody wore the same shirt. The fact there were people in our community saying, “Yeah, we’re still with you guys” — that was really special.

CHRIS #2: [In] February 2002, we did the Mobilize for Peace tour, bringing out peace activists and war resistors to come speak onstage with us.

JUSTIN SANE: People showed up saying, “I have been afraid to say how I feel, and the fact you guys are here is giving me a space to do that.” It was still a time when you couldn’t question what the Bush administration was doing.

PAT THETIC: The shows were awesome. But getting to the shows…

CHRIS #2: In Florida on the Mobilize tour, the bouncers were flipping us off while we were playing, and we had to get a police escort out of the show because it had erupted into a bit of a mob.

PAT THETIC: The shows in New York were a lot of union shows, so you have these old union guys who are socially conservative, don’t want to hear about your upside-down American flag, you talking about the U.S. military being a terrorist organization. Loading in, I remember them throwing our gear around, just being fucking dicks. We’re not fighters, and we’re not huge people… But activism is not supposed to be pleasant. It’s supposed to be uncomfortable.

CHRIS #2: We did the 2002 Warped Tour as well, and West Palm Beach was a really bad show. In retribution for [the Florida show on the Mobilize tour], kids came during our set, walked to the front of the stage, pointed at us, put mouthguards in, and started punching everybody. A huge brawl broke out, and we just said into the microphone, “We’re not going to play a note of music until you’re gone.” Your set at Warped Tour is 30 minutes long, and it took about 20 minutes for the rest of the crowd to see who they were. They turned on them, circled them, and we were able to get them out. And then we had a triumphant eight-minute-long set.

[Photo by Jen Palmer]

JUSTIN BIVONA (bassist, the Interrupters): In the wake of 9/11, when you’re a 12-, 13-year-old kid, thinking, “What is going on?” and then you find a band explaining what’s going on in the world, it’s eye-opening.

STACEY DEE (vocalist-guitarist, Bad Cop/Bad Cop): I remember Justin’s mohawk and Chris jumping off shit. They just looked shiny, and the crowds were massive, and they were going off. I don’t think I’ve ever seen Anti-Flag play to a crowd that didn’t go off for them.

TOM MORELLO: The Rock Against Bush tour in 2004… In addition to being the rock guitarist of Rage Against the Machine and Audioslave, I have a career as an acoustic troubadour under the moniker the Nightwatchman — and [Anti-Flag] took me out on tour. I was offered that year to tour on the Vote for Change tour — it was [artists like] Bruce Springsteen, Neil Young, Pearl Jam, Bright Eyes — they were doing a Democratic politics arena tour to get out the vote, and they asked me to play, and I said, “I would love to do it, but I think you should have a band like Anti-Flag on that tour.” And they were somewhat reticent — I’m not gonna speak for anybody in any of those camps — but because the optics of a band called Anti-Flag may have turned off some red state voters without ever listening to the band’s music.

So I opted not to do that tour, and [Anti-Flag and I] decided to do something of our own. Fat Mike or somebody got us a tour bus, and we rolled across the country in a tour bus that said ROCK AGAINST BUSH on it. We were egged in Florida… It was great. I’m going out, playing to audiences of 15- and 16-year olds, the shredding guitarist from Rage Against the Machine who’s gonna play his folk music before Anti-Flag tears the roof off the joint.

JESSE BIVONA (drummer, the Interrupters): They call themselves Anti-Flag, but their message was anti-establishment, anti-empire. Power to the people. Open your eyes to what’s going on in the world. Scream about it.

“The Rock ’n’ Roll Swindle”

CHRIS #2: With the cyclical nature of music, punk was coming back. That was plain for everybody to see.

PAT THETIC: When Green Day’s American Idiot came out [in 2004], we were like, “Thank God somebody’s able to bring these ideas to the mainstream.” Which is pretty amazing because American radio is about selling beer.

TIM MCILRATH: We had a good time teasing each other because everyone was signing. That tour was us, Against Me! and Anti-Flag, and eventually all three of those bands signed to majors.

CHRIS #2: I remember in New York City, [Rise Against’s A&R] guy being there and the four of us being like, “Ooh, you got a sleazy record label guy here!” It was funny to us because they would come around. I remember in D.C., in 2000, a guy who worked at a major label gave us his card, and he said something snooty like, “If you boys ever wanna take this serious, give me a call!” And then we were like, “Shove this up your ass.” So we had never taken it serious until our relationship with Tom [Morello] led us to having a relationship with Rick Rubin. Rick Rubin called in early 2003.

TIM MCILRATH: I remember I was at the Los Angeles Warped Tour, and I saw #2, Justin and Rick Rubin walking together behind one of the stages. What is happening right now? Rick Rubin cruisin’ around with Anti-Flag!

CHRIS #2: He said, “I loved the show. I want to sign your band. There’s gonna be a bunch of people who come in behind me who offer you whatever, but if you wanna make a record with me, I’m here. See you later.” And then, like magic, a car appeared, he got in and drove away.

CHRIS #2: Everybody tried to have some type of connection with us. Clive Davis’ was, “I worked with these activist musicians. Let’s talk about Bob Dylan.” It’s very flattering when someone wants to mention you in the same conversation as Bob Dylan. He also had a huge mobster desk, like 6 feet between you and him, whereas Jimmy Iovine’s office was supremely Los Angeles. The windows were open, and there were plants everywhere. You used a magic book to get in. Jimmy talked to us about his interactions with punk, his interactions with activists, which were mostly just stories about Bono. He says, “Actually, I have the new U2. Would you like to hear it?” He puts on “Uno, dos, tres, catorce,” you know, that U2 song [“Vertigo”] at an insane volume. As that song is elevating into its first triumphant chorus, Pat raises his hand and says, “Can you turn it down?”

JUSTIN SANE: You could just see the look on Jimmy’s face, like, “Wait, what?”

PAT THETIC: “I’m gonna be one of the people, man! These are the punk rockers. I gotta listen to it really loud!”

CHRIS #2: I can get into the weeds of the rock ’n’ roll swindle with Rick, if you want this story… Essentially, they gave us the pen to write our own contract… We make sure there’s money so we can give to activist communities. We make sure it’s a two-album deal and not some insane multi-multi-multi-album deal. We wanted health care, which is something we never had before. Ultimately, we turn in this insane contract.

JUSTIN SANE: When it all came to a head, Rick tells us, “I won’t allow you to sign this deal.”

CHRIS #2: Essentially, he was trying to protect us from being so in debt from minute one that they’re not gonna give [the band] a shot: “If you guys sign this contract, you guys have to sell a million copies, or else it’s a failure.”

We turned around and went to the other label, RCA, and said, “If you can beat this contract, we’ll pick you over Rick Rubin.” This was a bit of a white lie because Rick wasn’t gonna sign the contract, but we used it as a negotiation tactic, and it worked.

FAT MIKE: They got a very large advance, and it was guaranteed for their second record, too… So they could not get dropped… When I heard that, I was like, “Take it. I can’t give you that kind of money. And if it doesn’t do well, then you can leave.”

CHRIS #2: We put out two albums on RCA, and we washed our hands of it. We didn’t care [about Rick Rubin’s inhibitions] because our contract was sick, and we got to go home at the end of this experiment.

PAT THETIC: The studio we record our music in today… that major-label contract allowed us to [pay for] that.

SHANE TOLD: It’s funny that the major-label album is my favorite… [2006’s] For Blood and Empire, that album was a fuckin’ game-changer. One of the coolest things they ever did was sign to a major label and get their music out to a wider audience while still controlling what they wanted to do as a band.

CHRIS #2: For Blood and Empire and [2008’s] The Bright Lights of America, each record took three months to make. They cost exorbitant amounts of money. They were painstakingly perfect, to the point where we were chopping up bits, playing and playing till our fingers fucking bled.

PAT THETIC: We knew we were a punk band. We knew we were going to be a punk band no matter what happened with this.

[Photo via Anti-Flag]

“The Band and Their Message”

CHRIS #2: I think the darkest era of Anti-Flag is the end of 2008 until 2015. In those seven years, we did a lot of things I think are important, and we wrote a lot of good songs, but I don’t think we made a great album. I think all of us suffered emotional, physical stresses that were the result of being on the road so intensely from 2003 to 2008. I think we all fell out of love with the band because the band had taken things from us emotionally that we thought were pretty solid. The band became a job in those seven years. And that’s never a great place to create your art from.

CHRIS #2: There were a lot of special moments that happened in those years, but I don’t look back on those records and say…

JUSTIN SANE: It’s not our best stuff.

CHRIS #2: Both Pat and I had relationships that ended during that time. Head and Justin did as well. When people are grieving… gosh, I mean, before Bright Lights of America, my sister was killed. I didn’t grieve that properly because we gotta work!

JUSTIN SANE: If you have a four-person unit and two of those people suddenly become very unstable, it is really hard to make a solid plan. I didn’t go through the relationship disintegration that [Chris #2] and Pat did — basically a lifelong partner going away — but I was completely burnt out.

CHRIS #2: Pat wanted to quit the band in 2009. I wanted to quit the band in 2011.

JUSTIN SANE: It wasn’t a fun place to be. It really did feel like grinding through it. There were good times — probably the best times were when we were playing.

PAT THETIC: You have these ideals. You talk in interviews about the mission of the band. It’s real to us, but it’s not the grit. And then we go to a place like Ukraine [to perform in 2014]. We’re always talking to promoters, so we’re like, “What are the battles you guys are fighting?” They’re like, “We love your band. We love what you’re about. We’d love to have you come back and play this show again, if we exist and if I’m still alive.” And you realize there are tanks and bombs and people trying to kill these people a couple miles away.

That is a real expression of identity: “I am here, this is who I am, and someone wants to destroy me as a human being.” It had a huge impact on us.

CHRIS #2: We were getting from week to week, or tour to tour. And that’s not when we’re at our best. We’re at our best when we say, “This is our goal. How do we achieve it?” I don’t think we affirmed that again until 2015, when we made American Spring. Talk about a band betting on themselves. We went to LA, bought every flight, spent every dime to make the album, and at the end of it we held it up and said, “Who cares enough about this band to put this album out?”

JUSTIN SANE: Songs that we’ve written in the last 10 years, the last five years, are some of our biggest songs.

SHANE TOLD: American Fall was their new album [in 2017] when we went on tour with them. Watching the song “American Attraction” every night just explode, it was like, “OK, people aren’t here just to see ‘This Is the End’ or ‘Die for the Government.’ They’re here to see Anti-Flag. They’re here to see the band and their message.”

CHRIS #2: We have so many punk-rock contemporaries from the early ‘90s, and we play shows with them, watch their set, and they’ll maybe play the most current song, being from 2006. And 50%, 60% of our set is songs from 2015 to 2022… I mean, just look at the new album — it has eight guests on it, which is the first time we’ve ever done that. 2023 is the 30th anniversary of the band. Most bands when they hit 30 years, they’re doing a 30-year anniversary tour, and that’s it.

FAT MIKE: In debate class, I was told that whoever starts yelling the loudest is losing the argument. I always felt onstage if you just said the same things, you get just as much done. But I understand. They like to yell. #2’s mom probably yelled at him a lot — TAKE OUT THE GARBAGE! — and it got ingrained in him: HERE’S OUR NEW SONG! THIS SONG’S ABOUT SMALL WARS THAT ARE INSIGNIFICANT, BUT WE’RE STILL GONNA SING ABOUT THEM!

STACEY DEE: The truth is, they want the best for humanity and the planet and animals, and they want the best for this reality that we all are living in. They really, really do.

PAT THETIC: I’ve listened to leftist political philosophy all day long. And it all comes down to don’t be an asshole.

TIM MCILRATH: If there were critics of what they do, it would always be how in-your-face they were and how direct their lyrics were. You would hear somebody say, “Oh, it’s Anti-Flag, and they’re gonna play ‘Fuck Police Brutality.’ What an obvious statement.” But I’ve been alive long enough where it’s like, “Wait, there’s not enough people saying ‘fuck police brutality.’”

CHRIS #2: When we started, we were like, “That cop was a dick to Justin at the show,” so we wrote “Fuck Police Brutality.” And now you go to [this year’s] Lies They Tell Our Children, and we’re a band that’s traveled the world. We’ve got relationships in all these places. We’ve seen universal health care and universal education. We want to advocate for those things within our music. One of the questions we get asked a lot is, “You’ve written songs about these things so many times. Aren’t you sick of it?” And it’s like, “No, because every moment feels like a possibility to alleviate suffering.”

In our office, we have a framed letter of a person who had signed up for the military and was being asked to go but filled out the forms properly because they got the information from a table at an Anti-Flag show. And they were able to get their registry into the U.S. military revoked. I’m like, “That’s it. We won. There’s no greater reason for us to be a band than this piece of paper right here.”