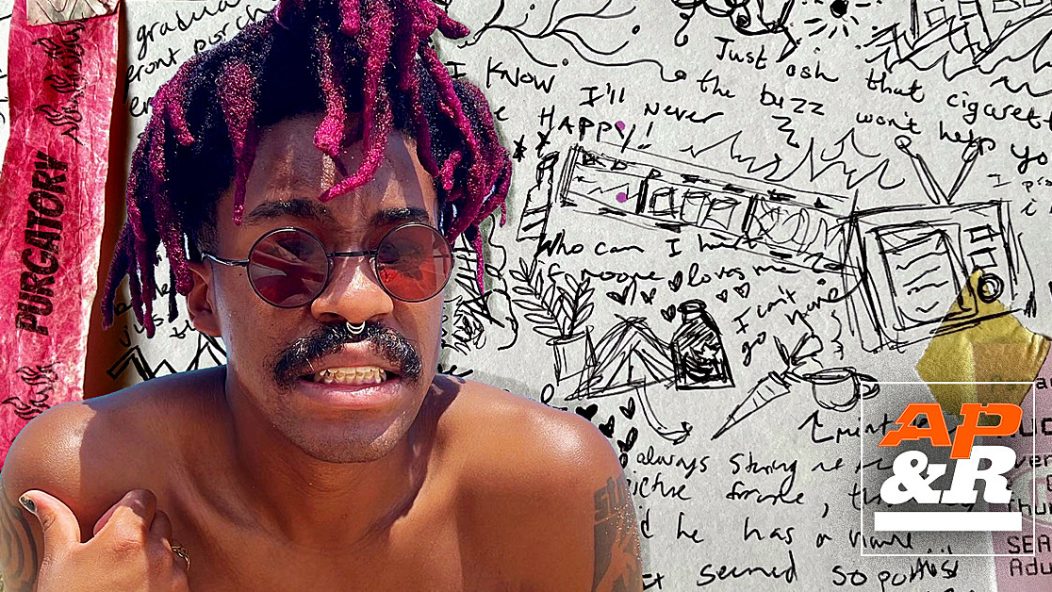

Indie band Blvck Hippie aspires to overhaul the DIY scene and uplift artists of color

Welcome to AP&R, where we highlight rising artists who will soon become your new favorite.

There was a unique sense of community when Blvck Hippie, a self-proclaimed sad-boy indie rock band, got on stage at Brooklyn’s Purgatory to perform in late summer 2022.

It was in that wall-to-wall pink room with a maximum capacity of 74 that Josh Shaw, lead vocal and guitarist, saw a safe space for people of color in alternative spaces. Following local Black-fronted bands like Rest Ashore and 13th Law, the Memphis-based group opened their set by acknowledging how much they loved seeing other people of color embrace the DIY community. For Shaw, along with bassist Tyrell Williams and drummer Casey Rittinger, the entire ethos of their band’s music has been about making Black kids feel comfortable.

Read more: Alt-R&B artist Chiiild “retuned” his memories to make the genre-defying Better Luck In The Next Life

Blvck Hippie’s sound, while reminiscent of the Strokes and Blood Orange, has its own unique energy. Born in the dorm room of two University of Memphis music students, there’s an obvious academic approach to its mix of hard-hitting guitar riffs and the kind of lyrical vulnerability that gives you physical chest pain. Their 2021 album If You Feel Alone At Parties encompasses a painfully relatable sense of nostalgia and loneliness.

After a turbulent decade of nearly quitting music and battling mental health, Shaw has plans to return to the studio soon to create “the Blackest emo record of all time” — which might even include a drum solo from their 4-year old daughter. They joined us to help break down their sound, navigating the community, and their vision for the future of DIY.

How long have you been involved in music?

I started taking classical piano lessons at 12, but started pursuing music in the capacity that I do now around 20. At the end of my sophomore year, I had a close friend get killed, I lost my grandma, and then I went through a breakup – just back to back to back. That summer I picked up a guitar and started writing songs.

You have songs like “Rhodes Avenue,” where you touch on your childhood. Was music something that was pushed in your household?

I don’t really come from a musical household – artistic, but not musical. The reason I took piano lessons was because I wanted to teach myself Beethoven songs. Then my parents realized, “Oh, he’s this weird homeschool kid. Let’s add a piano to the mix.” Neither of my parents played any [instruments], but they would always play music. They got me to listen to a pretty eclectic mix of all genres from all decades – everything from Marvin Gaye to the Talking Heads.

Do you hear any of that in the lineage of the music that you make?

Definitely. I feel like my sporadicness and scatterbrained writing style is directly pulled from that. I didn’t really look at music from a genre standpoint. I just looked at it as good music or bad music, as opposed to categorizing it. I don’t really go into writing with any specific genre idea in mind.

There’s a kind of nostalgia in how I write. I’ll try to remind myself, or bring back the same feelings of when I was like 5, 6, and 7, listening to my parent’s music in our small house on Rhodes Avenue.

![[Photo by Roy Jimenez]](https://www.altpress.com/files/2022/09/attachment-Roy-Jimenez-IG-%2540roythewanderer-1.1.jpg?w=630&h=945&zc=1&s=0&a=t&q=89) [Photo by Roy Jimenez]

[Photo by Roy Jimenez]

I’ve seen you describe your sound as “sad boy indie rock.” But there seems to be a lot of genre blending. How would you describe where that sound comes from?

In the early days, I was making a lot of weird, abstract lo-fi stuff in my dorm room. I feel like [my current music] is more of a combination of my experiences from writing a lot and listening to a variety of music growing up, but also my experiences in the punk and hardcore scene in Memphis. We called ourselves [“sad boy indie rock”] because I didn’t want to do anything that could’ve pigeonhole us too much. I don’t really like being in a box, especially as a Black artist – it’s the main thing you have to fight against. We made up a cool, catchy name for it, so it wouldn’t force us to have to sound like anything other than what we want to do.

I know that you say you primarily write sad songs. Do you have any lyrical influences?

I was 20 when I started writing lyrics, and it felt like I was starting behind most of my peers. So, I came at it from an academic standpoint. I decided to study a bunch of songwriters. I studied the Strokes’ entire discography because they were my favorite band. I studied every single Julian [Casablancas] lyric and how he writes, analyzing every little detail. I did the same with Julien Baker. Now, I feel like I’m pulling mostly from really vulnerable rap songs and a lot of midwest emo. When I was studying a lot of Julian, I was trying to use a lot of metaphors like he did, and hop lazily through topics. Now, I’m starting to come into my own.

You’re a huge fan of Kid Cudi. Can you talk about Kid Cudi?

Listening to Kid Cudi was the first time I ever saw a Black person say they were depressed, and I had a lot of terrible mental health issues. I was 15 when it really started getting really bad mentally, and that’s when I started getting into him. He had a lyric about nightmares in “Pursuit of Happiness,” and it blew my mind. It’s the first time I ever saw a Black man be vulnerable. It was like every time he dropped an album, it perfectly correlated to my life. Then he released Speedin Bullet 2 Heaven [in 2015] and there was this Black dude making a grunge album, playing all the instruments, and being super vulnerable about men’s mental health. And I knew I wanted to do that. I want to be everything that Kid Cudi was for me as a kid, but for everybody else, like for all the other kids coming up. He set the blueprint for my entire life up until this point.

![[Photo by Roy Jimenez]](https://www.altpress.com/files/2022/09/attachment-Roy-Jimenez-IG-%2540roythewanderer-1.2.jpg?w=630&h=945&zc=1&s=0&a=t&q=89) [Photo by Roy Jimenez]

[Photo by Roy Jimenez]

When I say you guys in Brooklyn, you opened up your set talking about the importance of having a community for people of color. Can you talk about your own journey with that, specifically within this scene?

I remember going to catch a band by myself after coming back to Memphis from college, and I was the only Black person there. I went there by myself, and everyone kind of stared me down as I walked in like, “What’s this person doing here? Who does he know?” I remember being very uncomfortable, but I didn’t want to leave. I dealt with that for years, and it just made me want to create a world where that isn’t a thing. My whole band has experienced that, as well. There’s so many weird, alternative people of color in every single community, and I feel like it’s so hard for them to find spaces where they feel comfortable when they explore less traditional, less stereotypical, interests. It took a lot for me to fight through that for years, and sometimes I still feel uncomfortable in DIY spaces. I just really want to make sure our shows are safe spaces for these kids.

What do you think can be done to address that in the DIY and punk scene?

I feel like representation is a huge part of it. People are going to feel safe in those spaces if they see someone on stage that looks like them, and bands on the bills that look like them. There are so many bands composed of people of color, but it’s so hard to break into those scenes – especially since they’re already kind of outcasts in a way. Venues and promoters have to go out of their way to find these Black artists and put them on the bills because just saying, “Support Black artists” isn’t enough. You have to seek out these artists, put together all-Black shows at your venue, and advertise in communities of color because there’s so many weird Black kids in the neighborhoods that aren’t being talked to. You have to go above and beyond the fight against the systemic oppression of Black art in general.

If there was something you could tell other aspiring bands dealing with the same issues, what would it be?

Don’t care about anything. Don’t care about how many people are at your shows, don’t care about having people write about you, just drown out the noise. Just focus on doing what you want to do and enjoying it. Don’t compare yourself to other artists, and just focus on the art and everything else will come.

Also, surround yourself with people to help because you can’t do it all alone. I feel like one of the hardest things I’ve had to learn was to let other people help. Focus on the art, don’t be afraid to let people help, and surround yourself with people that believe in you as much as you believe in yourself.