Braid’s Frame & Canvas at 25: the oral history of an emo landmark

Today, Braid are a happy band. Happy to still be friends, happy to be about to go on tour, happy to have just rereleased their landmark 1998 album, Frame & Canvas. As for being hailed as godfathers of Midwest emo, “happy” isn’t quite the word. Amused? That’s more like it. All in all, they’re grateful. Grateful their career-defining third album ignited a DIY scene far beyond the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and far beyond their native Midwest.

Frame & Canvas dropped April 7, 1998 on Polyvinyl Records. It was five years into Braid’s career, and it appeared as an underground breakthrough. Frame & Canvas sold around 15-20,000 copies on first release and took the quartet around the globe. Then suddenly, before the calendar could shift to the new millennium, the band were no more.

Read more: Every Dashboard Confessional album ranked

Speaking to Braid recently, there’s still a range of emotions about their 1999 split. The songwriting chops of guitarists Bob Nanna and Chris Broach had been sharpening by the month, and the pinball rhythm section of bassist Todd Bell and drummer Damon Atkinson — who’d replaced original drummer Roy Ewing in 1997 — was legendary to anyone who’d seen it up close. “Those [final] shows were bittersweet, but they weren’t sad,” Bell says.

But every so often, the stars realign. Braid reunited for a string of shows in 2004, and again in 2011, which ultimately led to a well-received comeback album, No Coast, in 2013. Polyvinyl Records aged well, too. Over the past two decades, releases from indie-rock bands like Alvvays, Japandroids, and Of Montreal expanded the label’s audience well beyond Midwest emo. Albums like American Football’s 1999 self-titled debut, and of course Frame & Canvas, are always there to bring Polyvinyl back home.

Braid are at peace, and that’s why they’re about to spend this July on the road. How they got here — that’s another story. Let’s rewind to 1997, half a decade before emo broke the mainstream, to a college town two hours south of Chicago. Here is the story of a Midwest emo classic, told by the voices of those who were there…

MATT LUNSFORD (co-founder, Polyvinyl Records): Two words are coming to mind when I think of Braid: super creative, super ambitious.

BOB NANNA (vocalist/guitarist, Braid): There was a spot in our basement where we were able to practice. The way I remember it, we practiced every night.

CHRIS BROACH (vocalist/guitarist, Braid): We were living all over each other, you know what I mean? And we were touring nonstop. That’s where Frame & Canvas came from.

DAMON ATKINSON (drummer, Braid): We were all figuring it out, together.

TODD BELL (bassist, Braid): We fight like brothers, we get through it. The good times and the bad.

BROACH: We were living in Urbana, Illinois. We all lived together in a house.

NANNA: A college town. It was really split. There were the people who were there to go to school, do school-related things, be in frats and sororities. And then there were the people who were there for the scene.

BROACH: We didn’t hang out at the college bars… We played a lot of shows in a [nearby] area of Champaign called Downtown Champaign, the local bars where all the bands would play. That’s where all the townies, if you will, would hang out. And people like us…

NANNA: What we helped bring to Champaign was this DIY house show idea. It wasn’t organized until we got down there. Mike Kinsella was down there, and he started American Football. And Polyvinyl being around helped that all-ages, DIY part of the scene develop…

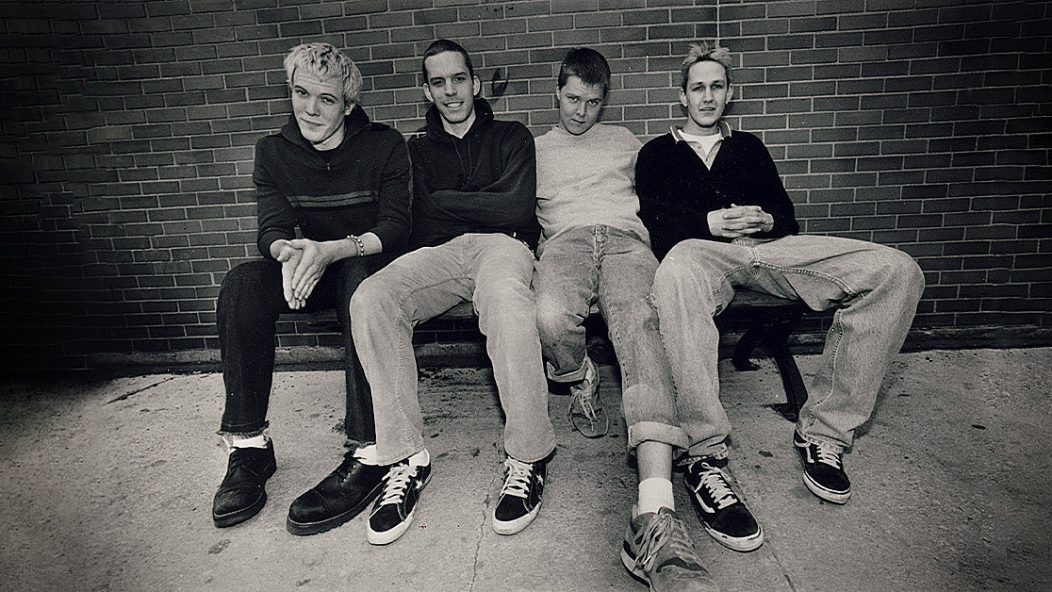

[Photo courtesy of Polyvinyl]

LUNSFORD: Polyvinyl started in 1996. My wife Darcie, then girlfriend, we’d just graduated high school. We were involved in the DIY scene in our hometown, Danville, Illinois, which is about 35 miles from Champaign-Urbana. Braid were friends of ours. We skated with Todd and [original drummer] Roy [Ewing].

The amount of things that happened between late 1996 and early 1998 is pretty remarkable: We decided to drop out of college to see if we could make Polyvinyl a full-time endeavor and really be supportive of an artist. We put out the first Rainer Maria record [1997’s Past Worn Searching], and that did pretty well.

KAIA FISCHER (guitarist/vocalist, Rainer Maria): I can’t remember ever feeling competitive with Braid. We were side by side on the same bill so many times. It was never like, “We’re gonna get ‘em this time!” Everybody was always so psyched for everybody else’s set.

CAITHLIN DE MARRAIS (vocalist/bassist, Rainer Maria): I feel like Chris from Braid and maybe Todd were the ones that told me that we were considered an emo band. We went to the Braid house, and on the wall someone had… the Remo drumheads come in the box with the word “REMO,” and they had cut out the “R.” I looked at it, and I just said, “EMO.” I clearly remember someone from Braid saying, “Well, that’s the genre that we’re in. That’s the joke.” I was like, “Ohh…”

When would you say we started getting lumped in with the Midwest emo scene, Bill?

WILLIAM KUEHN (drummer, Rainer-Maria): Maybe that [1997] Braid tour… I think the association with Braid and Polyvinyl lent itself. People would put [the word “emo”] on flyers because they wanted kids to come to the show, if they thought emo was popular in their town.

BROACH: If you listened to early Braid, the first seven-inch was a lot heavier, maybe even closer to first-wave emo than… whatever wave we are.

LUNSFORD: Braid had put out their first two records. The first one [1995’s Frankie Welfare Boy Age 5], the label it was on, was almost kinda self-released. The second record [1996’s The Age of Octeen] had come out on Parasol, another local Champaign-Urbana label.

NANNA: When we finished recording Age of Octeen, we immediately started writing new songs… We all kept journals on tour. I remember we wrote “Never Will Come For Us” in somebody’s living room on tour.

BROACH: There were interpersonal things. There were things happening with girlfriends… Heartbreak, being an insecure 20-year-old not knowing your place in the world.

KUEHN: I vividly remember [on tour with Braid in 1997] Chris and Bob — we’re staying at someone’s house — they’re sitting on a bed and writing songs for the [next] album… The one I feel I heard them writing was “A Dozen Roses.” It was just so, so catchy.

FISCHER: Bob had a real dedication to storytelling. That song “A Dozen Roses” [opening with the line], “A dozen roses in the car and I don’t know where you are.” Like, fuck! It drops you in the middle of a film.

LUNSFORD: Braid was trying to figure out a home for their third album. We wanted to do it really badly.

BELL: [Matt was] like, “If you want to do your next record with us, we’d love to have you guys.” Polyvinyl had just done the Rainer Maria record, and we realized how pro Polyvinyl was becoming, for their size.

BROACH: Matt was reliable, and he offered us a good deal, a 50/50 split.

LUNSFORD: That set the tone for the entire ethos of the label, being a 50/50 partner to artists. It’s something we still practice today… We subtract expenses from whatever money the record made and then divide by two.

BROACH: He agreed to pay for us to go work with somebody we grew up idolizing…

ROBBINS (producer; vocalist/guitarist, Jawbox, Burning Airlines): Jawbox had broken up, and I was working at Inner Ear Studios [near Washington, D.C.].

BELL: Years before, we all went to see Jawbox play in Champaign. We made them cookies. I remember giving them to [Jawbox bassist] Kim Coletta at the merch table and just being starstruck: “Oh, my God, we love your band. We just wanted to say we love you.”

ROBBINS: I worked with Texas Is the Reason, which led to working with the Promise Ring, which was a really wonderful relationship. All these bands were friends, or friendly acquaintances. There was a great cross-pollination of inspiration.

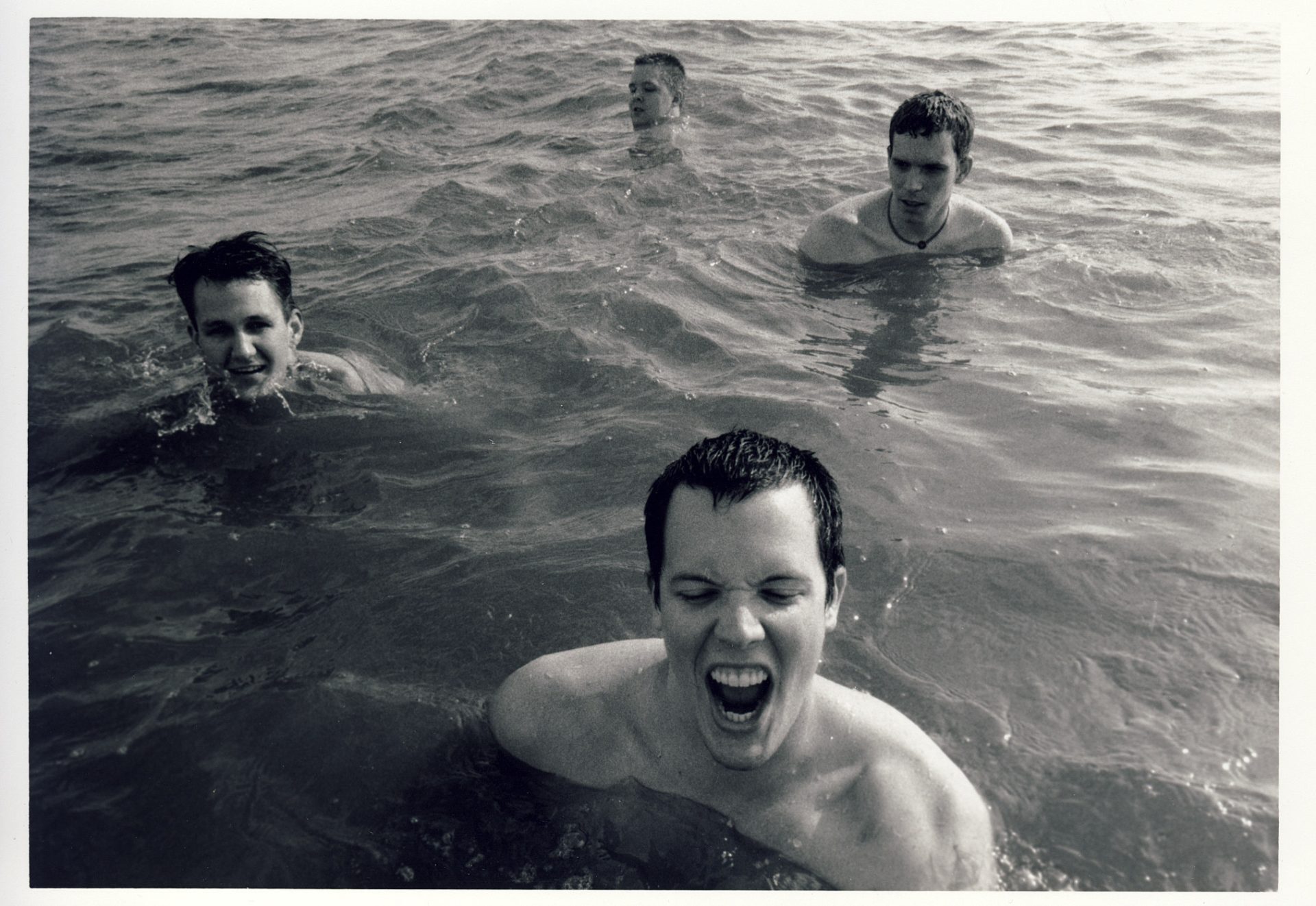

[Photo courtesy of Polyvinyl]

LUNSFORD: I remember hearing a few of the Frame & Canvas songs live. I don’t remember hearing too many demos. And then they went out to D.C. with J and made the record in lightning speed.

BROACH: It was a whirlwind. We got there…

NANNA: It was a blur.

ROBBINS: Five very long days… But they were super sweet and funny and cool. Such good energy. There was a bit of worry because it was an unfamiliar studio. Bob’s got to sing a whole record, and his voice can be fragile. Sometimes it did get kind of blown out.

I remember hearing “The New Nathan Detroits” for the first time. Such a great song. It was just like, “Hold onto your hats…”

LUNSFORD: And it was done: “Well, here’s the record!”

BELL: The distribution part of us signing to Polyvinyl was the thing we were really excited about. I can show my mom, “Hey I’m in a real band. Tell aunt whoever our album’s [in stores]!”

ATKINSON: All of a sudden, there’s a lot more buzz. We felt like this record was done right. As we’re getting out there, we’re seeing people talk about it… You start noticing the difference in response. When I’d play “New Nathan Detroits” — that opening drumbeat — I’d see people get so excited because it’s the first track on the record. It’s the first thing they hear.

NANNA: We’d recorded the album in December [1997] and then went on tour at the end of January [1998] in Europe with the Get Up Kids.

BROACH: Part of going on tour was that we didn’t have to work, right? We had a per diem of 10 or 20 bucks a day. We ate cheap.

NANNA: Sometimes we got fed at the shows, which was awesome.

BROACH: If we did, then I got to keep my 10 bucks for the next day!

We didn’t have cellphones. We didn’t have social media. So you leave town for a month, and you might speak to somebody once, twice, maybe send a couple of postcards. I remember leaving town, having a girlfriend, and coming back and being like, “I don’t have a girlfriend anymore.”

NANNA: If there was a payphone, run to it, because Matt [Pryor] or Jim [Suptic] from the Get Up Kids would get there first, and they’re going to be on it for three hours.

MATT PRYOR (vocalist/guitarist, the Get Up Kids): Bob can be very silly, but he also takes what he’s doing very seriously: writing, performing, he keeps a journal of every show they’ve ever played… Broach was the wild card, always doing his own thing… Damon was sort of the baby-faced new guy, and he was the only other guy at the time in the whole crew that didn’t drink at all, so he and I would hang out because I didn’t drink at the time… And Todd’s just a goofball, coming up with fake languages to speak, weird word games to play in the car.

NANNA: It was both bands’ first time in Europe, so there were a lot of moments where we were experiencing firsts together.

BROACH: Like the first grenade thrown into the backroom.

PRYOR: It was our second night in Germany, and we didn’t know what the political climate was there, if Nazis were coming after us.

BROACH: Some hooligans threw it backstage through a window. Luckily, nobody was in the room at the time.

In Europe, some of the places we were playing were even more DIY than the places we played here. A lot of squats. People took over some mansion we stayed in. Remember that place with the skulls in the basement?

NANNA: I think it was in Switzerland. I had a picture of Todd standing next to a bunch of skulls.

BROACH: We were up in this giant attic with tons of old garbage and this old electric chair sitting in the attic.

[Photo courtesy of Polyvinyl]

ATKINSON: Frame & Canvas was out, we traveled to places, and there’s hundreds of kids excited that we were there. The shows had an energy you can’t replicate.

LUNSFORD: They put a ton of emotion into playing live. And I don’t mean in a cheesy emo way.

ROBBINS: Those guys always had a sense of opposition in their arrangements.

PRYOR: How would I describe Braid’s live show then? Energetic, but that’s underselling it. They come from a Fugazi school of punk performance. A lot of jumping, landing in weird places. A lot of disregard for the safety of your body.

NANNA: After Europe with the Get Up Kids, we got home and went on tour with Compound Red. Then we went with the Get Up Kids again in the U.S. on the West Coast. We went on tour with Discount up to Canada. And then we ended [1998] going to Europe again with Burning Airlines.

BROACH: The band dynamics were interesting at that point. We were having a bit of a hard time. We were cohesive, we played really well, we wrote great songs. But interpersonally, things weren’t amazing.

BELL: You’re out west, there’s a lot of long drives, your van’s breaking down, everybody’s in a bad mood. You’re in a small space, so you get on each other’s nerves. I’m sure people hated me on certain days. I had to wake everybody up. Who wants to get woken up? That sucks. Gotta get up and go! We got a nine-hour drive if we’re going to make the show!

BROACH: Braid was on the road eight total months in 1998. And I went on tour for another month with a side project.

NANNA: You got home for three days, and you were antsy.

BROACH: We used to call it post-tour depression, or PTD. And it’s real. You got home from tour, and you’re like, “What the fuck am I gonna do?”

ATKINSON: We flew to Japan from D.C. I think Kim [Coletta] found those flights for something ridiculous, like $250 per person. But that meant we went from D.C. to New York, New York to Anchorage, Alaska to Seoul, South Korea, to Tokyo. Like 27 hours of traveling.

NANNA: We had a show in Japan, and there was a dude, a fan of ours in Hawaii, who was like, “Hey, I can book a show for you in Hawaii, too.” We’re like, “That’s great! If we do really well in Japan, we should fly our girlfriends to Hawaii for the show and then stay for a week.”

BROACH: We all felt a little bit like ballers.

BELL: None of us had ever been to Hawaii.

NANNA: We got to Japan, and the shows were not as good as we thought. Maybe I was just too cranky from being on tour, the long flight, and being crammed into this van. We were at each other’s throats, fighting a lot, and I think we ended up losing money. When we got to Hawaii, we’re broke, we don’t want to be around each other. And here we are with our girlfriends in paradise, and we have no money.

BROACH: The shows in Hawaii, did we play two or three?

NANNA: We played three. Two at the same club, and then we played a house show… We thought it was going to be really big… The dude paid us $40… He was really sweet, a genuine fan… [But] I don’t think people knew who we were.

BROACH: I remember wanting to go out to dinner and being like, “You know what? Let’s just go to the beach. That’s free.”

NANNA: I don’t think we hung out at all.

BROACH: Our communication broke down.

NANNA: We got back, and we played Empty Bottle [in Chicago] with Alkaline Trio. Then we played Krazy Fest. Krazy Fest was in Louisville…

BROACH: And we were driving from Chicago… I didn’t drive down with the band because I didn’t want to be in the van with the band. I was going to meet them there, right? And I brought my girlfriend at the time… There were no cellphones then… I was late to the show and pulled up during what our set time was supposed to be.

NANNA: It was the time [zone] difference, as well. It was an hour later.

BROACH: I thought, “Fuck!”

We were all going to hang out with Promise Ring that night, and they were like, “You should come.” I went back to the hotel and hung out with my girlfriend instead. Then we met at Krazy Fest the next day… The Krazy Fest people allowed us to play… and it was uncomfortable.

NANNA: It wasn’t too long after that we broke up.

BROACH: We did three songs at Coney Island [Studios] in Madison, [Wisconsin]… I remember feeling beat up about Japan and Hawaii, and there was just a thickness in the studio that day… We literally finished mixing the last song, and we’re like, “Should we go outside and have a band meeting?” And that was it. I think we all knew exactly what that meant. It wasn’t a happy thing. It was just a necessary thing.

LUNSFORD: We talked about it on a phone call, if memory serves.

FISCHER: A lot of stuff changed around that time. You know, flipping over to the new millennium. Everybody wanted to do new stuff.

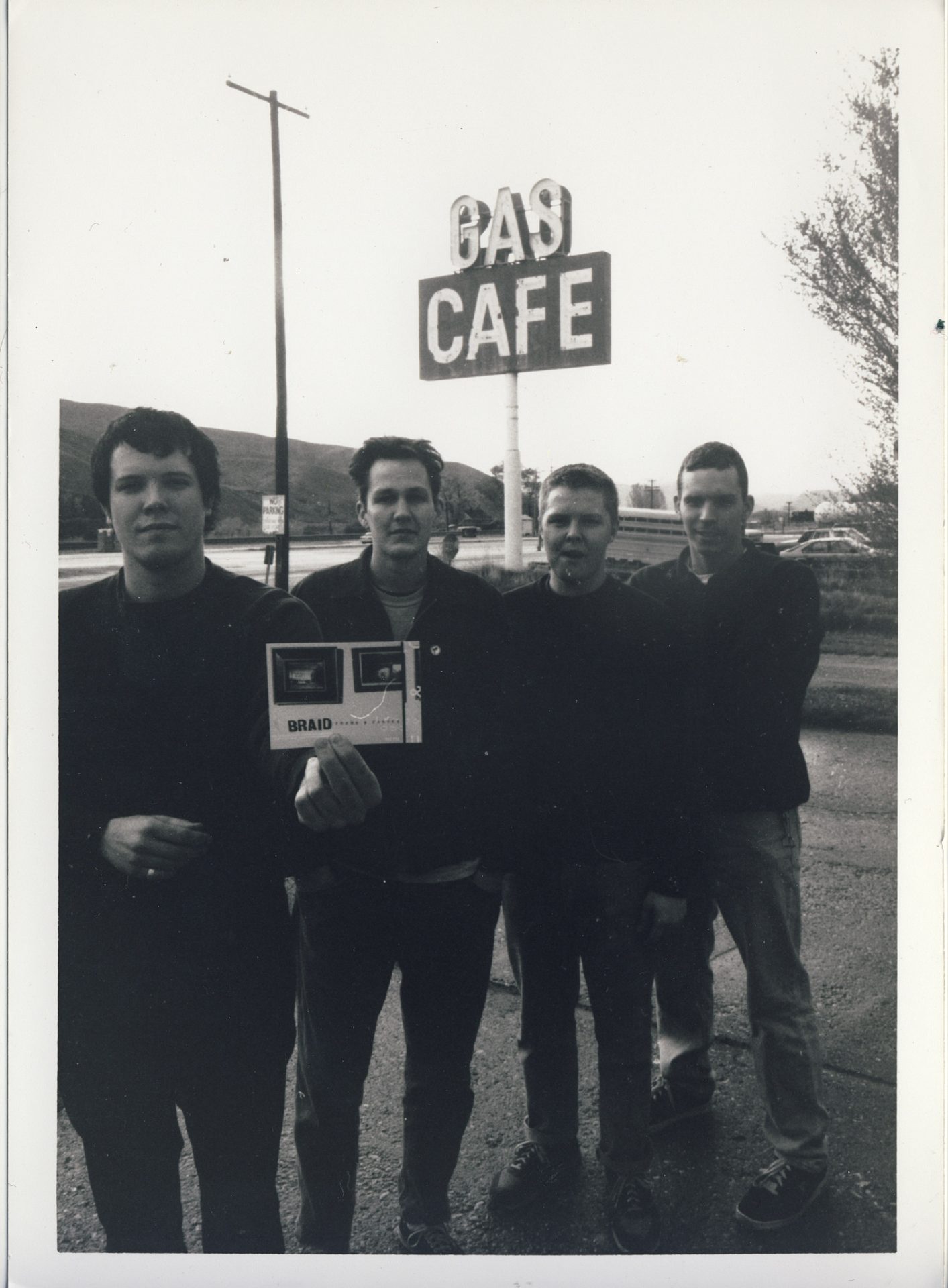

[Photo courtesy of Polyvinyl]

BROACH: I don’t know where the idea of last shows came from, but I don’t think we decided that day. We went home and decided what we were going to do…

BELL: Damon’s from Milwaukee. We were gonna play a Milwaukee show. The band’s from Champaign-Urbana, we’re gonna play there. And we’re gonna play in Chicago because Chris and Bob are from there. It was really personal to hit the cities we came from [in August 1999].

We were like, “We’re stopping being a band. And if you want to come see us play, we’re playing the Midwest. We’re going to have one show you can get advance tickets for, so if you’re driving out from someplace far away, you’ll at least be able to get into the Metro show [in Chicago]. We’re not going to sell it out. It’s huge. We’re Braid. We’re not going to sell it out. That’s where I grew up seeing bands I thought were the biggest bands in the world.”

LUNSFORD: Frame & Canvas was the entire focus of Polyvinyl for almost an entire year. We gave that record a lot of attention.

ATKINSON: That Metro show sold out.

BELL: Like, “Is this a mistake?” Those last shows were so successful for us, we’re like, “Oh rats, maybe we should stay a band? Maybe it’s a fluke because we’re breaking up and people know this is the last time they get to see us?” I don’t know. But it was very bittersweet.

ATKINSON: We put a sign on the [Metro] door that said, “If you weren’t able to get tickets, go to Fireside Bowl. The band is going to play there… In the DIY scene, that’s where everybody played… That show we had an idea… It was somebody’s parents’. Maybe Bob. There was a wheel…

NANNA: My mom was working at a retirement community, and they had this big spinning prize wheel they used for their fairs. I think there were 32 spots on it. We brought the wheel onstage, and each number had a song title on it.

BROACH: We played whatever song it landed on. Wasn’t there a prize underneath each song? I remember you gave away, like, a teapot?

NANNA: We gave away stuff from our band. Somebody won a grocery bag full of cassettes.

BELL: Those songs were ingrained in us. We didn’t even have to rehearse. We were used to going out and playing 20, 25 songs in a set, because we could, and we wanted to. If people wanted us to play, we were gonna play.

NANNA: The last show was at Mabel’s in Champaign.

[Photo courtesy of Polyvinyl]

BROACH: I remember the last song we were playing. It was “I Keep a Diary,” right? Maybe “Chandelier Swing.” I remember going behind my amp because I started to get choked up. Like, “This is going to be our last song ever.” Going behind my amp and hiding. I didn’t want to, like… and I’m not…

NANNA: Just say it. Emo.

BROACH: Yeah, yeah…

ATKINSON: Tears of joy, but also tears of sadness: “Oh shit, man, this has been so much fun. Too bad it’s gotta end.”

There were plenty of people there who were like, “Why would you break up? You just put out a record a year ago, and it did so well. Why would you break up?” It’s hard to answer that for anyone else where it makes sense to them. It made sense to us.

BROACH: Afterwards, I remember people coming up and being bummed. It was just like, you know, what am I supposed to do with that? Like, “Me too.” But at the same time, it did feel right.

NANNA: I distinctly remember talking to somebody after the show who was really upset. And I was not feeling that at all. I wasn’t mean to the guy, but I was just like, “Everything’s great. I don’t know what to say.” I remember it feeling like a job well done, in a weird sort of way.

ATKINSON: A lot of bands, companies, and relationships fail when it comes to money. You know, if there had been a lot of money made and it was mismanaged or it wasn’t distributed fairly. That’s where a lot of people get really ugly. Lucky for Braid, we never made any money.

BROACH: People talk about Frame & Canvas more than I ever thought they would. It’s the gift that keeps on giving.

ATKINSON: It’s still a decision we’re totally OK with because our lives, collectively and separately, have gone in this trajectory since then. And we’re all here now, rereleasing Frame & Canvas and celebrating its 25th anniversary.

FISCHER: Its uniqueness is not lost on us. A lot of [bands] have done things with that mathy, smart, double-vocal, double-guitar interplay. But at the time, that sound was really coming out of nowhere. And it had a massive influence [on] the whole musical idiom that we know was Midwest emo.

ATKINSON: A couple months ago, before the announcement of the Frame & Canvas 25th anniversary [album rerelease and shows], we had a marketing meeting with the team at Polyvinyl and some other individuals that we hired out, Bittersweet Media, who handles our digital stuff. We get on a Zoom, and there’s 14 people. I’m like, “Damn, this feels like a business meeting! This feels like the real deal.” It is, but I have my job, Todd has his job as a schoolteacher, Chris has his job. We all have our jobs outside of this. The band is not our job. It’s fun.

ROBBINS: There’s an energy those guys had. Super high energy. But also, there was a warmth. Some bands have that real pissed-off kind of energy. It might be a sort of darkness or theatricality. But for Braid, there’s just a sense of joy, you know what I mean? That’s the first word that comes to my mind: joy.