After eight years, Broken Bells are back with their most experimental album yet

Since their formation in 2008, Broken Bells, comprising the Shins’ James Mercer and prolific producer Brian Burton, aka Danger Mouse, the duo have risen above the “supergroup” connotation often assigned to them. Unlike the subset’s forefathers — Cream, the Highwaymen and Audioslave, to name a few — Mercer and Burton are not making hodgepodges of their own interests. Instead, every Broken Bells project is an amalgamation of the duo’s unrelenting and far-ranging talent, pinnacles of each artist’s most soulful interests that mesh in an almost otherworldly way. And on their newest LP, INTO THE BLUE, 12 years after their first, Broken Bells have reached an apex that is vivid, cosmic and daring.

The story goes that Mercer and Burton met in 2004 at Roskilde Festival in Denmark and became fast friends, keeping in touch over the next few years, playing demos for each other and sporadically crossing paths on tours. Before Broken Bells were finally assembled four years later, Mercer was working on the Shins’ third record Wincing the Night Away, while Burton and CeeLo Green released the Gnarls Barkley debut St. Elsewhere. “When [Mercer and I] met, I had really just started producing, making beats, that kind of thing,” Burton says. “I actually listened to ‘An Easy Life’ the other day, and it was funny how we went in, without ever doing anything together, and I think we had a song in a day, or two, so that was a good sign.”

Read more: Arctic Monkeys aren’t done evolving

What makes Broken Bells such an achievement for both Mercer and Burton is how the project allows each songwriter to step out of their own comfort zones. With the Shins, Mercer has long been a staple in indie rock, and songs like “New Slang” and “Australia” have found long-lasting acclaim. Behind the boards, Burton broke out with The Grey Album, a masterpiece convergence of Jay-Z’s vocals from The Black Album and the instrumentals from the Beatles’ S/T (“The White Album”). But with Broken Bells, and especially on After the Disco and now INTO THE BLUE, the duo are exploring post-disco, funk, psychedelia and experimental pop to forge some of the best electronica this side of the millennium. Broken Bells are, in many ways, an always-evolving continuation of The Grey Album: a convergence of Burton’s hip-hop compressions and Mercer’s grandiose, traditional melodicity, components that, on the surface, feel alien next to each other but create magic when pooled together.

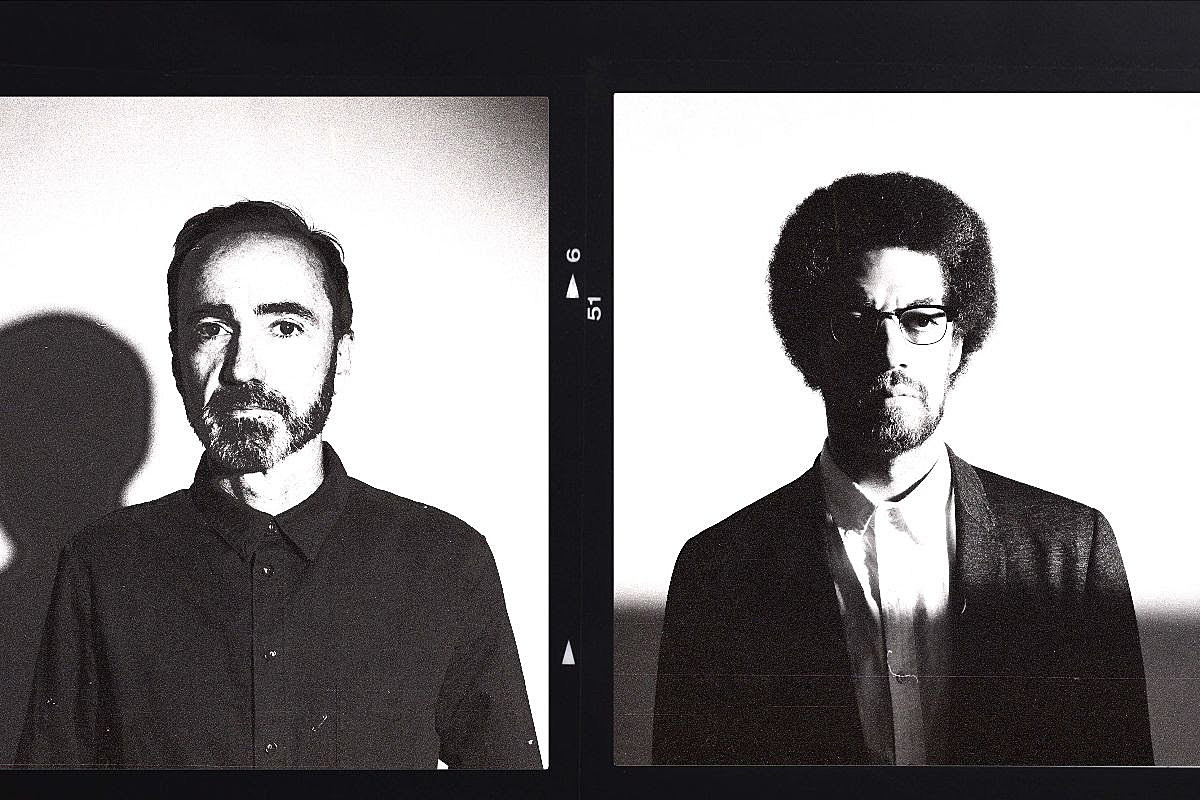

[Photo by Shervin Lainez and Nikki Fenix]

The eight years that have passed since After the Disco shouldn’t be categorized as a hiatus, because that would imply Mercer and Burton took a voluntary absence from the work. But in that gap, along with a pair of singles, “Shelter” and “Good Luck,” released in 2018 and 2019, respectively, Mercer and Burton’s partnership didn’t pause. “We never really stopped working,” Mercer says. “Whenever we would have time, and it seemed easy, we would get together and just continue the process of searching for cool ideas.” In the time since After the Disco, Mercer put out the Shins’ record Heartworms, and Burton has worked on Adele’s 25, Red Hot Chili Peppers’ The Getaway and Parquet Courts’ Wide Awake!, and they’ve transitioned from Columbia Records to AWAL.

INTO THE BLUE was meant to arrive much sooner than 2022. Though “Shelter” and “Good Luck” don’t appear on the final cut of the album, Mercer and Burton assumed a full-length project would naturally follow those singles. “I don’t think we know when we’re going in whether something is going to wind up being a standalone thing, or not,” Burton says. “[We’ve] never really done anything in that way. I think we didn’t want to be gone for so long.” Because of the pandemic, the four years without a new record quickly turned into six years and then seven and so on. “I remember thinking that, if we got the album done soon enough, we could use ‘Shelter’ and ‘Good Luck’ on the record,” Mercer adds. “But time passed too quickly.”

With any good musical partnership, there’s a certain level of trust at play. For Mercer and Burton, their friendship has vaulted them into a dynamic that thrives off having confidence in each other’s interests and techniques. “For me, I trust [Burton’s] taste,” Mercer says. “When he introduces something to me, I feel like there’s something great [there], and I just have to dig in and find it. It makes it easier to work hard on something.” With Mercer handling the vocals and many of the arrangements, he’s able to lean on Burton’s keen productional eye and work with him to construct a final shape. “I think, when something is outside of yourself, it’s so easy to judge it than it is when it’s something of your own work,” Burton adds. “The way we work together, we don’t really even have to say so much. We just know, when we’re trying stuff out, if the other person’s into it or not.”

Half of Broken Bells’ roots have always been dredged in hip-hop and R&B, but INTO THE BLUE is the first bona fide release that tinkers around with sampling in a frontal, methodical way. In 2015, Burton helped produce A$AP Rocky’s sophomore album, At. Long. Last. ASAP, and key production elements in that record’s foundation framed Burton’s sonic mindset for Broken Bells’ future. “I started working with samples again, which I hadn’t done in a long time, with [A$AP] Rocky, and he got me back into sampling again,” Burton says. “That just so happened to be at a time when [Mercer] and I started working on some stuff after After the Disco, after we toured and went back in and started doing some [new] songs, which turned into some of the stuff that’s on this album.”

What INTO THE BLUE does better than any other Broken Bells project, however, is yield an atmosphere for Mercer’s dynamic spectrum of vocals. The progressions filling Burton’s headspace offer challenges to Mercer and ask him to widen, and, to no surprise, he is always up to the task. On songs like “We’re Not in Orbit Yet…” and “Love on the Run,” his cadence hurdles across multiple octaves, from the chamber-pop richness on the former to a smooth, soulful bravado on the latter. Even “Invisible Exit” wades into crooning, indie-folk waters backed by symphonic strings. Burton made sure that Mercer’s vocal tracking was clear and spoke to the commanding presence it brings to any composition. “The biggest thing that happened that made it to [this album] was trying to carve out more space, from place to place, for James’ voice, wanting to hear his voice up front a bit more,” Burton adds. “It’s happened before, but I think it was a little bit deliberate, sometimes, on my part.”

Mercer’s aural abilities have long gleaned a tenor worthy of indie darlings, but it’s his Bee Gees-style falsetto, which flourished briefly on the Shins’ Port of Morrow and at full speed on After the Disco that have elevated the potential of any Broken Bells composition. “I think I pushed myself to find new melodic choices and rhythmic things that are different from what I’ve done with the Shins,” Mercer adds. “But there’s also natural inspiration that occurs in the studio with [Burton].”

A lot of that inspiration builds off the duo’s unyielding trust in each other and Burton’s song-building roots in hip-hop, which he’s carried over into his work with other singers, but especially Mercer. “The thing about hip-hop is, when I first started doing that, you make beats and then you play it for somebody and they sit there and listen to it over and over again, and they rap over it,” Burton adds. “And that’s how I work with vocalists. I’ve done that with [Mercer], too. I’ll bring him something, and I would never think to do what he winds up doing.”

The way the chapters of INTO THE BLUE came together was organic. As Mercer puts it, he and Burton get together and mess around with instruments until they find something cool to run with. “When we would find something, some chord progression or whatever we liked, we would record that and then just loop it, begin elaborating on it and building a song that way,” Mercer adds. Burton’s sampling changes the dynamic, but nearly everything started from scratch in the studio.

Given how the pandemic postponed Mercer and Burton’s ability to finish INTO THE BLUE, the duo was able to keep refining the songs they’d come up with, as opposed to “just doing more new songs,” as Burton puts it. Having that availability and space was something they’d never encountered in such a palpable way before, and it granted them the access to make the tracklist the strongest one yet.

Many contemporary musicians are trying to reintroduce older sounds into their own sonic palettes. In turn, they cycle through a lot of elements that feel more like a pastiche than a connected sound with a single throughline. But for Broken Bells, on INTO THE BLUE, the compositional diversity and the arrangements mesh beautifully. On “Love on the Run,” in particular, the song traverses a long plain that takes shape as a piano ballad, funk dance number heavy on horns and a psychedelic guitar eruption. Mercer and Burton are able to revisit these moments in music history without overselling anything.

While some artists take these retro sounds and try to play them authentically, Broken Bells are doing the opposite, almost because they have no other choice. “I can’t pick up an instrument and play very well. I can fool around and get some happy accidents and try to get an idea down, but I think that, because I’m not such a good player, I found a lot of tricks and shortcuts and things that just break it a little bit.” Burton says. “[The arrangements] are not so classically done, but the love for where the stuff comes from is still there, so it has that familiarity.”

The mixture of new and old that has come to define a Broken Bells album is the product of Mercer and Burton each occupying a different part of the duo’s repertoire. Mercer is a well-versed multi-instrumentalist, while Burton can shoulder a track to the finish line like few others. “I think the broken element to things, the limited abilities of myself and James, who can play really well and sing really well, [when] you mix them together, just has something a little different to it,” Burton adds.

It’s rare to see a pair of friends, both of whom are often doing other things, like raising kids or racking up Grammy nominations, so generously return to each other as if no time has passed. INTO THE BLUE sounds nothing like the Shins’ Oh, Inverted World or Gorillaz’s Demon Days or the Black Keys’ El Camino, and that’s wholly the point. The things Mercer and Burton get stoked on, like the Beatles and the Elephant 6 collective, often overlap. You can see the stems of the duo’s other work poking through on INTO THE BLUE, but what shines most is how each of their passions and interests get translated so uniquely into the well-oiled, undeniably groovy machine that is Broken Bells.

“Even if we both love something, we both love something completely different about it,” Burton says. “I might be hearing it completely differently than he’s hearing it, but we do enough of it where it works.” What will come next for Mercer and Burton hasn’t been written yet, but INTO THE BLUE is a stark reminder that sometimes our best work arises when we’ve got someone we trust to lean on.