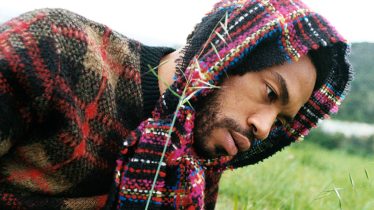

On After Hours, Delicate Steve comes home

Whether we’ve recognized it or not, Steve Marion, the man behind Delicate Steve, has been at the vanguard of contemporary music since 2011.

On top of being a self-proclaimed “critic’s and artist’s artist” with a rich catalog of six studio albums, Marion’s performed live with a bounty of revered alt-rock, psychedelia and surf-pop mainstays, such as Dr. Dog, Built To Spill and Mac DeMarco. His collaborations with Paul Simon on Stranger To Stranger, session work with Sondre Lerche and the post-rock project Seltzer Boys helped define experimental pop in the 2010s. Marion found his creative apex, though, when he received word that Kanye West sampled “Wally Wilder,” a cut from his 2012 album Positive Force, on the now-scrapped song “Slave Name” in 2019.

Around that same moment, he lent anthemic guitar phrasing to the noise-pop Cherry Glazerr track “That’s Not My Real Life” from Stuffed & Ready. Marion’s most notable and hallowed alliance, however, came a year prior with Damon McMahon, when he performed extensive guitar work on the lionized, euphoric Amen Dunes LP Freedom. “Needless to say, I was in a pretty insane place for myself as a musician,” Marion tells AP over the phone while stationed in Greece. “That gave me a lot of confidence to make Till I Burn Up, which I feel like was a confident left turn. I just wanted to try something and not be afraid to fail.”

Read more: 20 greatest punk-rock guitarists of all time

Though Till I Burn Up — Marion’s prismatic, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy-inspired breakout dressed in fuzzed-out guitars and alarm clock synths — was an industrial deviation from the Eliminator-era ZZ Top riffs on 2017’s This Is Steve, his joyous, memory-culling instrumentation endured on both and reappears on his newest LP, After Hours. After Till I Burn Up entered the world, the Black Keys tapped him to be a featured guitarist on their “Let’s Rock” U.S. tour, before COVID-19 nixed the shows and Marion relocated to Tucson, Arizona to escape the bedlam. On unemployment and consuming many curiosities within the desert’s vastness, Marion didn’t play or think about music for a year. “It was a big reset for me and one that I didn’t know I needed,” he adds. “So when it came time to make [After Hours], I felt like I was coming from a strong and centered place.”

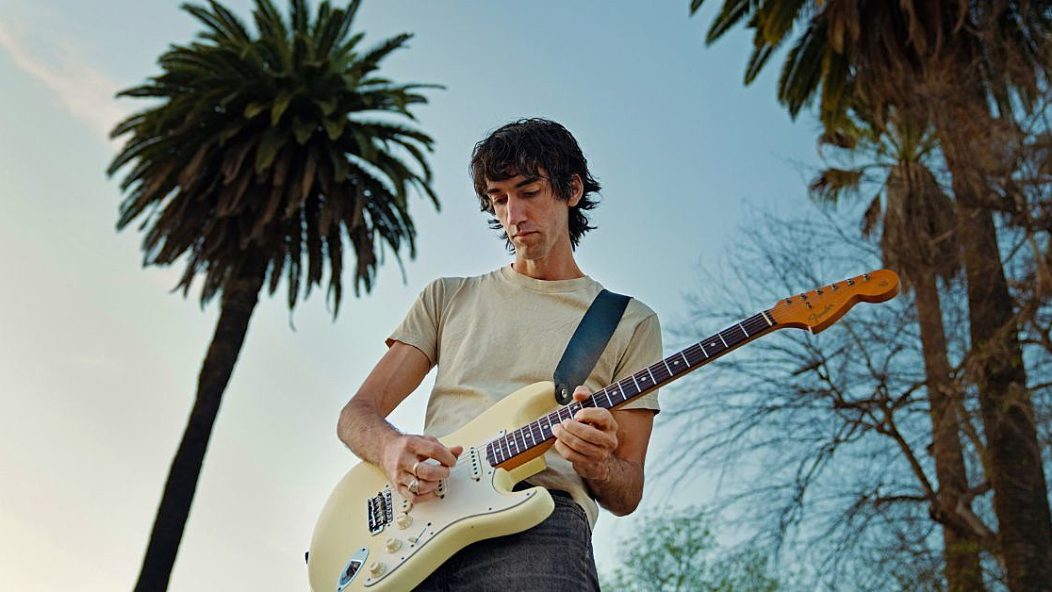

Because of that time spent away from music, After Hours is Marion’s grandest statement yet. The LP — written and recorded on a 1966 Fender Stratocaster at Figure 8 in Brooklyn and Eli Crews’ Spillway Sound in the Catskill Mountains — sports a rich landscape of psychedelic loops and solos, accentuated by Pakistani bassist Shahzad Ismaily’s grooves and Brazilian percussionist Mauro Refosco’s forró. Ismaily (Plastic Ono Band) and Refosco (Red Hot Chili Peppers, David Byrne) help Marion craft monumental, stratified songs that are bluesy, wayfaring and quixotic; voiceless articulations of joy and nostalgia. “[Ismaily] was a very nurturing presence and gave me a lot of confidence as an artist,” Marion explains. After Hours isn’t just his return to solo work; it’s also a reignition of his love for the electric guitar.

Marion was spending time in Tucson with his dear friend, Dr. Dog’s Scott McMicken, when a conversation between the two guitarists planted a seed in the former’s psyche that allowed him to properly reunite with the instrument. McMicken had listened to Marion’s live rendition of “Hallelujah” and finally understood what defined Delicate Steve for him. “[McMicken] said, ‘Listening to [“Hallelujah”] brought me to tears, and I realized that Delicate Steve is not about the window dressing of the aesthetics; it’s about the phrasing on guitar,” Marion recalls. “It sounded so obvious when he said it, but I never thought of it that way.”

Read more: The 1975 prove how heartbreaking violin can sound on “Part of the Band”

That realization not only helped Marion refocus his own identity in a deep, meaningful way, but it transported him back to a decade ago, when he was in his early 20s fashioning a singular instrumental oeuvre amid a budding Brooklyn/Baltimore music scene that featured Dirty Projectors and Deerhoof. “All of these bands were incredible and infusing such new life into music. That inspired me to deviate from convention on guitar playing. So [After Hours] was a return to a deeper version of what I think I am, which is a guitar player,” Marion adds.

Guitar records have been a predominantly idle subdivision of rock ’n’ roll for some time now, save for the outputs of Joe Satriani, Steve Vai, Jeff Beck and Buckethead. Marion understands that he’s in his own lane, mostly separate from the contemporaries who’ve emerged from the same scene. “While the indie scene is something that’s used to describe so many different textual genres and people playing, there’s not really another artist making these guitar records where the guitar is a lead singer,” Marion says. “In that way, I feel like I’m doing something exciting. In some ways, I’m thinking like a singer and playing guitar like a singer.” Without using lyrics, Marion focuses on melody through instrumentation, joy through colorful chord progression.

On After Hours, Marion’s chord progressions and solos evoke as many emotions as words, every note as equally meticulous as they are raw. “I Can Fly Away” buoyantly conjures Penguin-era Fleetwood Mac and Funkadelic with dancing, soulful riffs and celestial backing harmonies from Queens, New York singer Breanna Barbara and multi-instrumentalist Tall Juan Zaballa; the title track is a one-take, improvisational pastiche; “Looking Glass” sees Marion’s guitar adroitly converse with Refosco’s ticking congas. “I only write songs for Delicate Steve through recording them,” Marion says. “The process works in a very linear way where I get an idea for chords or drums or guitar, put it down, and if that inspires something else, I’ll add on top of that.” Previous Delicate Steve albums found Marion laser-focused on keeping the songs tight. On After Hours, he lets the freedom of baggy, unconstrained sounds float alongside each other. The product is an ingenious collection of ‘70s soul, African rhythms and Technicolor, sonic spirals — a mesh of once-disparate sounds shaped into a kaleidoscopic, instrumentally grand voice.

Read more: How Joyce Manor reconnected while making 40 oz. To Fresno

But Marion never used to think about how an instrumental project could sing in ways a voice cannot. In fact, he used to be against the idea of “instrumental” — the word felt “inhuman” to him. “A big reason I named my project after myself and put my face and my name on it was to humanize my instrument and sound and make it feel as relatable as possible,” he says. “I think the human voice is the most relatable instrument that exists — and I don’t have one.” Musical accessibility is a big fixation for Marion, as he’s constantly hurdling over not having a human voice by mining for new ways to enrapture an audience without saying a single word. “I do want as many people in the universe to hear my music as possible and relate to it,” he adds. “And while it doesn’t have this singular relatable instrument, the intention behind it is deeply trying to connect with other people and not trying to push anybody away.”

Delicate Steve has always been Marion’s artistic channel. On previous records, he was the singular performer. But on After Hours, Marion opens his aural worldbuilding to an alchemy of session players he’s long admired. Alongside Ismaily and Refosco is an all-star lineup: Rosalía and Chance The Rapper organist Jake Sherman provides Wurlitzer and clavinet; Austin Vaughn — who’s played percussion for Cassandra Jenkins, another past collaborator of Marion’s — and Jeremy Gustin lend their drumming chops; prolific composer Stuart Bogie arrives with his saxophone in hand; Martin Bonventre shines on the Rhodes piano and JUNO-DS88. “Everyone brought a very intuitive performance, which is not always the case with music, especially when people are trying to fit into a certain sound,” Marion adds. “It can sometimes be a struggle, but this record feels like the opposite of that to me. I’m just floored by the performances on the record.”

The chemistry of his supporting cast on After Hours helped Marion make, what he says is, his most enjoyable record yet. For This Is Steve and Till I Burn Up, he’d turn the final masters in and never listen to them after the releases — unless he had to overpower fits of self-consciousness and convince himself the work he did was OK. Marion’s affection for After Hours is otherworldly and new territory, in that he has kept the record on repeat since its completion. “I think a huge part of that is me hearing the work of these other musicians because, otherwise, I would just be hearing myself. That probably wouldn’t be too exciting for me, which is why I haven’t listened to the other records as much.”

Read more: 20 best stripped-down songs, from Spiritbox to Silverstein

Though his previous record was much more, as Marion puts it, a “geometrical head-turner,” After Hours has become so important to him because it comes from a joyful, soulful place within. He’s also always been a guitar player, and After Hours has been advertised as his homecoming with the instrument — but it’s eons more than just a remarkable musical reunion. When the Wurlitzer tolls and the guitars sing on “Playing In A Band,” there are curiosities being unlocked by both the listener and Marion and his crew together that hold steady across the album. Each song is a palace waiting to be triumphed; a shelter to be settled in. That idea of home is always changing for Marion. In a literal sense, he’s hoping to move out of the States and settle in Greece permanently, but, musically, he’s shape-shifting across genres and attempting to articulate emotions through the mystical.

“Home for me has always been, and hopefully always will be, exploring consciousness, in the same way that human beings are, and just continuing to push things in every direction all of the time,” Marion adds. “I would say that the last thing that is ever going through my mind is a style of music to be conformed to. The guitar is my voice.”