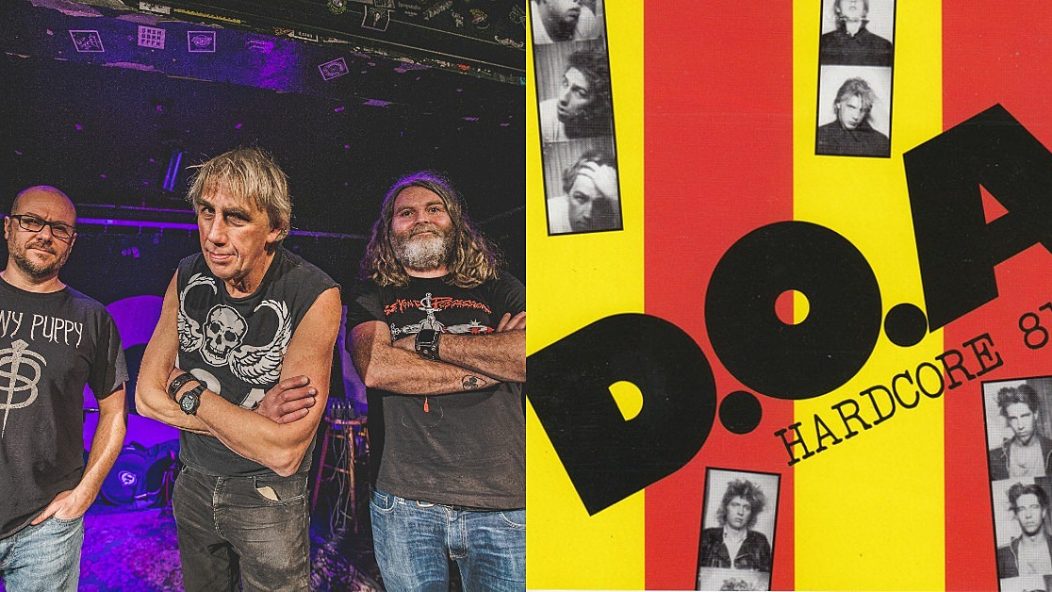

DOA discuss the legacy of second album 'Hardcore 81'

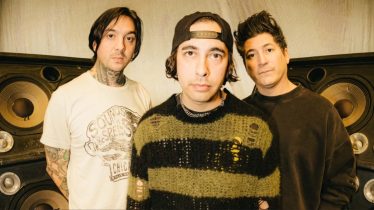

Burnaby city councilman Joe Keithley (aka “Joey Shithead”) has led Vancouver, B.C. punk pioneers D.O.A. since 1978, the band’s sole mainstay. In part one of our conversation, he was interviewed one hour before going onstage. The trio — these days, guitarist/vocalist Keithley, drummer Paddy Duddy and bassist Mike “Corkscrew” Hodsall — were touring to commemorate the 4oth anniversary of their second album, Hardcore 81. In part one, Keithley spoke of his long-standing political activism, which led him to seek office, succeeding with his 2018 Green Party Burnaby municipal election bid. This time around, he reflects on Hardcore 81’s role in popularizing and defining an entire musical genre/social movement.

With all this political awareness you had early on, English punk was natural for you to get into once it came along.

JOE KEITHLEY: Yeah, that whole working-class approach. I think the first benefit we did as a band was for Leonard Peltier. I remember the FBI was trying to get him because they claimed he’d shot two of their agents at Wounded Knee. He got into Canada, because of his status as an Indian, so he could cross the border. Someone in Vancouver asked, “Do you want to raise money for Leonard Peltier’s defense fund?” We said, “Fuck yeah!” That was me, [original D.O.A. rhythm section] Chuck [Biscuits, drums] and Randy [Rampage, bass] within the first two or three months we’d been a band.

The classic D.O.A. lineup. As well as guitarist Dave Gregg later.

KEITHLEY: Yep, the early stuff. [Turns to his current rhythm section.] Don’t worry, you guys are good, too! [Laughs.]

Well, you’ve always had good lineups. You don’t pick bad musicians, ever. But Rampage, Biscuits and Gregg set the tone for D.O.A. for all time.

KEITHLEY: When we got Dave in the group, I was like, “Eh, he’s not a very good guitar player.” Our manager Ken [Lester] said, “But Dave will be like the George Harrison of the group!” [Laughs.]

D.O.A. are on a tour celebrating the 40th anniversary of Hardcore 81, an album likely responsible for naming an entire movement, even though that term was circulating by that point. What’s interesting to me is that D.O.A. have always sounded to me more like classic punk rock than what’s come to be thought of as hardcore. Certainly, you have some faster songs. But I think “hardcore,” in your case, meant more like the term’s actual definition.

KEITHLEY: We took it more as an attitude, as opposed to a sound. It was definitely circling around. I think it might have been in Damaged magazine out of the Bay Area. We were there in ‘79, ‘80, and this article came out, quoting me about hardcore. I was like, “Oh, D.O.A. is one of the only hardcore bands around.” I named Black Flag and a couple of other bands like that. But the author was writing things like, “There’s this new movement in punk rock that is loosely called hardcore.” Of course, we read this with great interest. When we got back, Ken Lester said, “Well, we’re recording our second album. We should use that hardcore title.” He came up with two suggestions: Hardcore Plus or Hardcore 81.

So then we did the first hardcore festival that would have been called that. That would’ve been February or March 1981. We got Black Flag up for one night. 7 Seconds was supposed to play one night but they couldn’t make it, so we got Section 8 instead. We had local guys like Bludgeon Pigs and stuff like that. Then the album was out and the tour started. So that started the whole “D.O.A. are the godfathers of hardcore” that people express and stuff like that. But I’d say we were the progenitors of spreading that name around and stuff like that. Right time, right place. Which, as we know, is what music is about.

It’s more about a certain commitment to ideas and a certain ferocity than it is about how fucking fast you’re playing. That was what was so cool about Black Flag. Damaged is the most hardcore record you will ever hear, but it’s about how hard it is.

KEITHLEY: Yeah, and when you listen to New York hardcore…

…it’s just fast heavy metal! [Laughs.]

KEITHLEY: It’s got its place, and there’s some good bands in there, for sure. But that’s not what we envisioned in the first place. It mutated by ‘85 or ‘86. Because by then, punks started getting into metal. Some were OK with it, and with some, it just destroyed whatever they were before. A few put out some tragic records, which I won’t name right now. I don’t really blame people because you’re always trying to figure out how to get ahead in music. There’s probably no tougher business, except maybe being a comedian. Comedy is tough because you’re just by yourself. At least with a band, you have your friends.

MIKE “CORKSCREW” HODSALL: And most of the band usually likes the band you’re in.

Usually. It’s not always the case, however…

KEITHLEY: So, there was definitely a schism. I think you could definitely define D.O.A. as a hardcore punk band, as opposed to a hardcore band. I think people know enough to put that definition out.

HODSALL: We played a hardcore festival in the Czech Republic back in 2014, and we were like the Beatles. Everyone else was a lot of very angry young men going chug, chug, chug, chug. A lot of low-tuned heaviness.

That’s the thing: D.O.A. have always been as much a rock ‘n’ roll band as anything, the way the New York Dolls or the Sex Pistols were. I mean, you had early metal roots — I know what huge Black Sabbath fans you guys were. But what you did had as much Rolling Stones in it as anything.

KEITHLEY: Yeah, it was just sped-up backbeat rock ‘n’ roll, which is what we grew up listening to. Every radio station played that in the ‘60s.

DUDDY: [Led Zeppelin’s] “Communication Breakdown” was on Hardcore 81!

I love that you sang the verses a full-octave lower than Robert Plant. But Randy sang the choruses a la Plant.

KEITHLEY: We tried to get Randy to take lead on it, and it sounded horrible. Then Chuck did, and he sounded worse. So, I said, “OK, I’ll do it an octave lower. But you’ve gotta put an underwater effect on my vocal.” So, that’s what Tracy Marks, the producer, did. Hence the murkiness of the whole thing.

DUDDY: So, that’s Chuck and Randy singing the chorus? It sounds like Randy. It sounds like Annihilator [Rampage’s ‘80s metal band].

It’s certainly Randy. He certainly did the “Ooh, suck” part. [Laughs.]

KEITHLEY: Yeah, that was hilarious. Dave bent that note. Then Randy yells, “Suck!” [Laughs.] The funny thing about that record, eight or 10 months ago when we were getting ready to release it, we had to remaster it because there were lots of complaints about dropouts towards the end of the original tapes and stuff like that. We didn’t want to change the sound too much with remastering. So I asked the guy to be gentle on that. Then we had a hard time getting the three bonus tracks on that, all the singles. I just wanted to add something so it wasn’t the exact same release. So we finally got that matched up so it hit the flow without destroying the record. The first side was 11 minutes long, the second side was seven minutes long, with 14 songs — very short.

But going through that, with all the records I’ve done, I’ll listen to them really intensely for six to eight months, while we’re doing them and then when they’re out. Then I’ll look at a record and say, “Oh, I haven’t listened to this in five years, or 10 years.” It’s not that I don’t like them. It’s that I kinda ODed on them while writing and recording them. But I listened to this one in my van, which is always my go-to test to see if I’ve mastered a record properly. And I was like, “Fuck, this is a really good record!” I’d forgotten. I knew people liked it, but it dawned on me, “Yeah, the band is pretty good!” Not like I was shocked or anything, but yeah. “This fuckin’ rips!”

The first album was pretty good, too. But the difference between the first album and second album was that our manager wanted to get something a bit more like the Pistols. So he picked all the slower songs. All the Hardcore 81 songs were written around the same time as [first album] Something Better Change. Then we thought of this hardcore idea. So “Smash The State,” “I Don’t Give A Shit,” and “My Old Man’s A Bum” all fit that idea naturally. We wrote a couple of new ones, too.

DUDDY: It kinda ramps up, right?

KEITHLEY: Yeah. When a band’s young, you sit there and write a whole bunch of material. A lot of times, it ends up being the only material people remember. Even though you might make good records later, they’re never comparable and almost impossible. Not that people shouldn’t try, but if you try and recreate that madness of when you’re 20-25 years old? It’s hard to do when you’re 40 or 50. Even though you may be a more skilled guitar player or drummer, maybe know a little bit more about music, it doesn’t mean you’ll make that record. It’s that fucking madness that’s really intangible when bands make their first two or three records.

DUDDY: You’re really swinging for it, the first couple of records. You don’t really know what you’re doing. You’re just swinging for it as hard as you can. Later on, you know more, and you’re settled, and you know how to do things. But you don’t have that same urgency of flushing it out of the sky.

Hardcore 81 was so different from a lot of second albums from first-wave punk bands. Most of those bands peaked with their first albums, like the Pistols or the Damned. The Clash were a little different because they sustained it through the first three. D.O.A. didn’t peak with Something Better Change. You didn’t have that old dynamic of having your entire life to write the first album, then six months to write the follow-up. The tendency is to burn out after your first album.

KEITHLEY: My youngest son Clay is 26, and he’s a real fan of punk rock. He plays guitar and all that kinda stuff. We talked one day about how a band would be really hot. They’d be doing a record, go promote it, they’re writing more songs. Then the record company would say, “We need another album right now.” Look at the Ramones. They made all sorts of great records. But the first four are like, “This is the template to everything, as far as punk rock goes.” And they hammered those out in two-and-a-half years. And toured like 150 shows per year or more.

Apparently, the Ramones wrote the songs for the first four albums in one big lump. Then they recorded them in the sequence in which they wrote them. So that’s why those records feel like a piece. Those first four should be your Ramones collection.

KEITHLEY: Yeah, you need all four. It’s unbelievable how fucking good they are.