30 Years of AP: David Earle, AP’s First Editor, Guided it From Local Rag to International Mag

Dr. David Earle was the first editor of Alternative Press. A full 30 years later, the magazine and punk-rock never come up in conversation in his daily life, even when he writes scholarly books about periodical publications. But the magazine still informs his personal and professional world, whether he’s teaching college courses or breaking out some old vinyl.

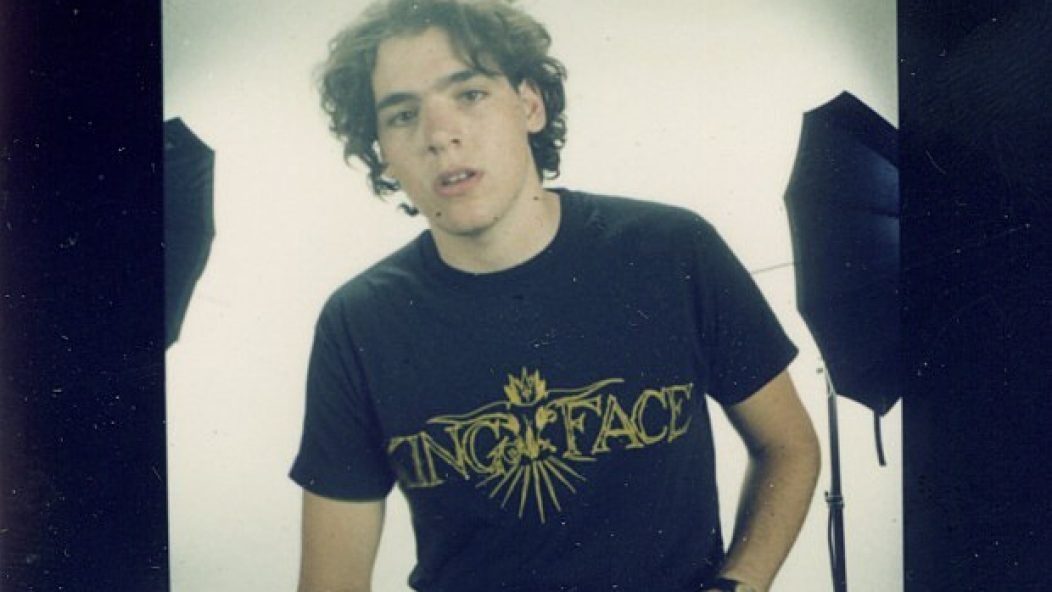

Photo: David Earle in 1988

“Dave was a good writer when we had hardly anyone that knew how to write that wasn't a skater,” reflects AP founder/CEO Mike Shea. “He was into really cool punk and was suburban like me, so I could relate to him—we were similar age and new-school. The older school dudes were mostly downtown and West Side, and they didn’t really embrace the new-school kids who had come up with MTV. They were the Ramones generation, and we were Black Flag.”

Working hand in hand with Shea, Earle helped grow the rapidly mutating publication from a free local handout to an internationally circulated glossy magazine that covered breaking superstars like Guns N’ Roses and Jane’s Addiction. With Earle holding the reins, the unpaid staff kept their fingers (sometimes as few as 30 fingers) on the pulse of all things underground, alternative, and underserved, including hardcore, jazz, blues, and an occasional Munsters interview.

Professor Earle took a moment from his academic sabbatical to reflect on the formative time when AP felt around, looking for an identity, a mission and enough money to publish one more issue.

Was there ever a point where you looked at the magazine and thought, “What has this become?!”

There were moments when it did not resemble the magazine we started, but [my reaction] was never horror. It was an overwhelming surprise. We struggled so much in the early years, that once it went national and international, and there was no question it was going to survive—that’s when I was surprised. The first moment I felt old was when there were bands on the cover, and I had no idea who they were, and they were really, really popular.

AP was at its most diverse when you were there.

My dad [Scott Earle, a.k.a. “Cyan Cerulean”] was the absent-minded professor. He wrote for computer magazines, and he was a surgeon. But he knew more about blues than you could possibly imagine. And we got him in because it was a mutual decision between Mike and I that we were trying to [make AP] be like a college radio station: be as inclusive as possible, and cover anything that was not covered in the local press.

The magazine was not only trying to find its identity, but we were trying to find our identity. When I started, I was 16 or 17 years old, and Mike was a year or two older. In our first year, we were trying to provide a service for Cleveland.

That vision of the magazine representing a gathering of the tribes—was it odd having that mix of people working together?

Not at all. That was one of the best parts of it. I came in as a writer on issue two or three, and pretty quickly became very involved. There were days doing paste-up or collation, which was a pretty horrible job of stuffing thousands of magazines. There were three of us in my basement or Mike Shea’s basement, living on [caffeine-rich] Jolt Cola and Little Caesar’s and cherry licorice until four or five in the morning. It was wonderful, fantastic bonding. It was great. But it was arduous. We really did feel we were doing something important.

David Earle today

AP went broke and temporarily folded in 1986. When the magazine returned, what changed?

When we returned from the hiatus, and we had writers from [nearby] Akron and all over the United States, it dawned on us that what we were doing was important nationally. I think that’s where the identity of the magazine really coalesced, at that moment. There was absolutely a new vision of the magazine, if you look at the covers.

The magazine was back, but the money problems weren’t solved yet.

Mostly what I remember was trying to find money to put the magazine together. Mike was borrowing money. He was having business meetings with sketchy guys. We put on these huge punk-rock shows, just to get money to pay the printing bills. That was desperation, and it was Mike’s idea. The first one, the promoter stole all our money, and we had to call the cops. A lot of the promoters in town saw us as a threat as the shows went on.

They were infamous for years in Cleveland. We packed the Variety Theater, which was this old, 1927 theater that was decrepit and falling apart. I’m sure if it was closer to downtown, it probably would have [become] a porno theater. We did matinees of local bands. Those were the craziest and busiest. Suicidal Tendencies was probably the most successful one. I think the least successful one was a hardcore band, MDC, in a different venue, JB’s in Kent. That wasn’t successful because the local booking agents were booking against us. Those shows were amazing, even though they were smaller. I was the guy in charge of pushing the divers off the stage.

What were some of the hard decisions you had to make in that period?

We were still putting local bands on the cover. I remember us really struggling with whether we should put [Cleveland punk band] Numbskull on the cover of issue number 7. But we loved the photo so much that we made the aesthetic decision to put that on the cover, even though, nationally, we knew nobody would know who they were.

And at that moment, we knew that this had a national scope. Spin had just started, and we really wanted to go against Spin; we didn’t think they were doing a good job. There were some good national zines, and there was Spin, and there was nothing in between. Mike saw that hole, and he wanted to fill it.

The change over those first couple years, all of those were conscious decisions that came from hours and hours of sweating and thinking about the direction we wanted to take the magazine. We’d have long conversations about “What is a magazine?” “What is a newspaper?” “What is a zine?” Since going into academia, I’ve written two books about magazines. And I’m sure that’s because of those conversations with Mike. Alternative Press was foundational in my intellectual development.

You quickly grew from a kid with no writing experience to the editor. How did you develop those muscles?

The year hiatus, that was my freshman year of college. I was an English major. My second year, I almost flunked out, I dedicated so much time to it. One of the reasons I stepped down and became just a writer was I was on academic probation.

Who read the magazine in those first years?

We would print maybe 1,000 of them, and we couldn’t believe that we were going to get rid of them all. And they would go in a matter of hours. I remember walking up to [Cleveland neighborhood] Coventry, sort of the punk-rock central hangout, with the new issue. And I’d get into an argument with this kid because there were a lot of typos, and he was saying we shouldn’t charge $1.25 for a magazine with errors in it.

How did you determine what went in?

We all had voracious music tastes, and certain bands we all agreed on, like Love And Rockets, Nick Cave, Jane’s Addiction, the Laughing Hyenas. We were all just excited about covering the music. Coming from a small zine to suddenly having access to these bands that were incredibly important to us and foundational—of course we wanted to interview them and hang out after shows. And Cleveland was the perfect place, because every band that came to New York and went to Chicago went to Cleveland, and those shows usually weren’t as packed, and they had time to talk to us.

There were always these conversations about whether we should interview commercial bands. And as a punk-rock guy, I wanted to stay alternative. But at the same time, there was the pragmatic appeal that we wanted national appeal, and we wanted people to buy the magazine. So we would throw in these commercial bands, as well.

Who were some of the worst interviews?

Run—I think—from Run-DMC, was horrible. He was so bored. He would answer all my questions before I got three or four words out, because he had been interviewed so many times, and he was bored with the interview. Gang Green, a Boston sort-of hardcore band, the guy was a dick. I called the guy at the record label and told him we weren’t even going to cover his band, he was such a dick to me.

Who were the better ones?

For the most part, we got great interviews. The Melvins crashed in my apartment. Interviewing Big Black. Interviewing Fugazi before they had an album out. Driving to Columbus during a snowstorm to interview Scream, when Dave Grohl was in the band. I got to be pretty good friends with him, but I’m sure he wouldn’t remember me.

Christian Death, they just did not do interviews—that interview sticks out, because the tape recorder did not work, and I had to go do the whole interview again. That was important to me. I had gone to Catholic school, first through eighth grade. And that’s why I gravitated toward goth and punk rock, because I was questioning that.

What were your guidelines for balancing commerce and art?

It was always this conversation about tipping the point [about] who was going get us a few more thousand issues sold, to cement our national distribution, and to allow us to get our next issue out. Because we never knew if we were going to get our next issue out. And ultimately that conversation was always about the good of the magazine, as opposed to the kind of idealist hardcore kid inside me [and what I might have wanted].

And ultimately, you’ve got to put that on Mike’s vision and his gusto and his wherewithal to keep things going under pretty incredible circumstances. Even if we had a commercial band like Gene Loves Jezebel on the cover, inside, we got interviews with Fugazi or the Cro-Mags or Uniform Choice and hardcore bands that didn’t have that much of a national reputation.

As the magazine grew, how did Mike grow?

Mike was this super-sweet, enthusiastic guy. It was heartbreaking when the magazine took its hiatus. And he found the energy and money to start it up again. And at that point, he was all business.

I remember when the office was in my apartment, and I had been removed to having one room, and the magazine had the rest of the apartment. For a literally hot moment, he wanted us to wear ties, because we weren’t professional enough, and he wanted us to understand this was a business. So I would have to wake up in August, in a non-air-conditioned apartment, get into the shower, and put on a tie to walk into my living room. We rebelled after four days. That was the moment we got someone to sell ads full-time.

What do you think when you see what punk has become?

Punk rock, to my consideration, is still the last political subculture. I love the fact that kids who weren’t born yet are going back and listening to bands that have a political and anti-authoritarian message. There is still the potential for it to do the kind of work it was meant to do.

At the same time, it’s hard for me not to get into this “Hey, kids, get off my lawn!” attitude. As a teacher, I wish there was more self-awareness about the corporate colonization of the subculture. But if one out of 20, one out of 100 kids gets turned on to the Dead Kennedys or another band with a strong political message, and he questions the things around him, punk is still alive.

What did you personally take away from punk into your second life as a professor?

I’m tattooed—I look like an old punk-rock guy. It was absolutely foundational in my way of thinking. Even in the critical, literary work I do, my writings are anti-authoritarian, anti-academic. They really are the attitude of punk rock, applied to literature.

And there’s a whole generation of professors who have that anti-authoritarian, deconstructive attitude, who apply it to the way our parents and grandparents thought, and they break it down. So I think that’s one of the less realized heritages of punk rock. I don’t have kids, but I [teach] 100 kids every semester. I think of that every semester: how you instill in students the ability to question things around them. alt