15 artists who draw influence from the Clash’s dynamic punk spirit

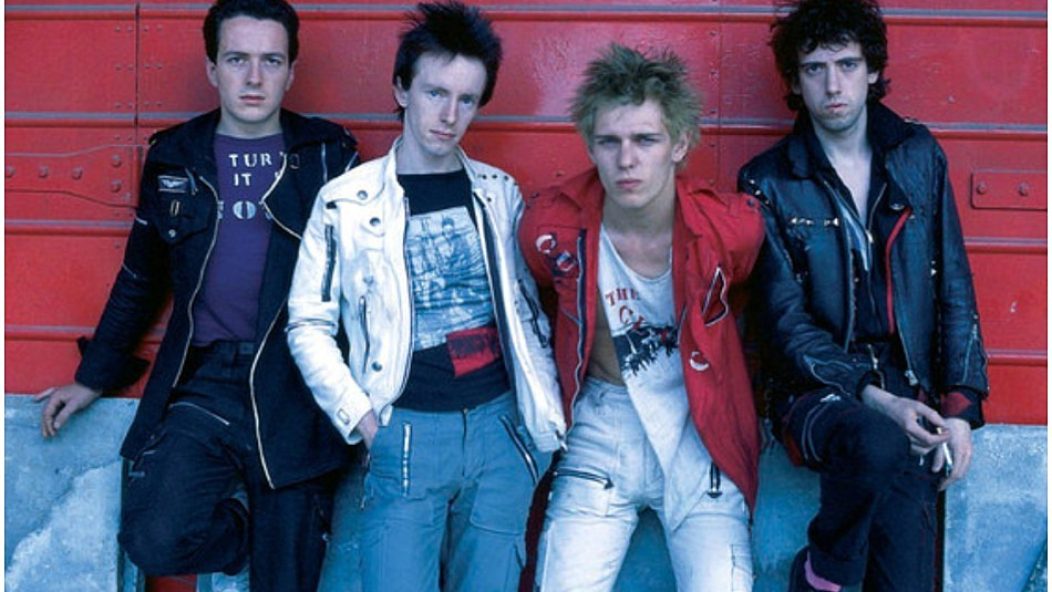

Some promo copywriter at the Clash’s American label, Epic Records, came up with the questionable slogan “19 songs by the only band that matters” for the sticker that appeared on the face of 1980’s U.S. release of London Calling. While singer/guitarist Joe Strummer, lead guitarist Mick Jones, bassist Paul Simonon and drummer Topper Headon didn’t coin the phrase, they also refrained from protesting it. This act gained them enormous mistrust in certain quarters.

True, there was a good deal of self-mythologizing to the Clash. Just listen to tracks such as “Clash City Rockers,” “Last Gang In Town” or “Four Horsemen.” It was a trait absorbed from glam heroes Mott The Hoople, one of Jones’ teenage obsessions. But the Clash truly were more than a mere punk band or even a rock ‘n’ roll band. They really seemed larger than life, especially if you were a teenager catching one of their first late ’70s U.S. tours. It felt like you were getting a cool, really loud soundtrack to lessons in how to walk, talk, dress and comb your hair. It’s as if they told you, “Maybe try wearing your belt buckle over your hip, like Paul. Oh, there’s this music called rockabilly made back in the ‘50s that you should check out—look in your parents’ record collection. And here’s this killer sound from Jamaica called reggae—we listen to it constantly. Here’s what’s going on in the world—keep an eye on your leaders! They are not to be trusted! Also, here’s a list of books you should probably read.”

Read more: 10 times punk rockers stole the show on American TV in the ’70s and ’80s

Plus, the Clash live had a unique attack. They didn’t have a frontman—they had a front line, like a tactical assault unit. Jones, Strummer and Simonon all came at you simultaneously, guitars slung low. It was nonstop running, jumping, total action. But Strummer was definitely the most passionate of the three, slashing at his Telecaster endlessly, his right leg pumping in tandem with his right hand. It felt like the singer was about to leap out of his skin, a giant exposed nerve, wanting to reach out to every individual audience member, grab them by the shirt and drag their face to his as he screamed, “Do you understand what I am trying to say?!” That frustration at his inability to make a direct connection was likely the source of Strummer’s unbelievable energy.

It was a lot like this video:

There was no one like the Clash. There’s been no one like them since. But plenty have tried. Some still are trying. That says something—the Clash are enduring and eternal. Here are 15 of the best lives touched by the Clash, in their brief lifetime and beyond.

Stiff Little Fingers

Being British, the Clash’s most immediate effect was in the United Kingdom. Their passionate commitment to their sociopolitical point of view and their explosive musical attack came across even more effectively live. Yet, there was something disingenuous about their blowing into Belfast, Northern Ireland for an Oct. 20, 1977 gig at Ulster Hall, finding the gig canceled due to the insurance company pulling out, and posing for publicity photos in front of bombsites and tanks. (They played a stormy gig at Dublin’s Trinity College the next night.) Stiff Little Fingers lived in Belfast. It was their lives before which the Clash were modeling. It went into singer/guitarist Jake Burns’ songs—tales of the effects of a generations-long war for which no one remembered the root cause (“Suspect Device,” “Alternative Ulster,” “Bloody Sunday”), of feeling entrapped in a nowhere town (“Gotta Gettaway,” “At The Edge,” “Breakout”), how authority represses the youth (“Law And Order”). Those ringing lyrics were set to a good approximation of the Clash’s debut LP, with Ireland’s lilting melodic sense factored in. Plus, Burns had even more of a sandpapered rasp than Strummer. SLF even embraced the Clash’s punky reggae amalgamation via blistering covers of such roots material as Bob Marley’s “Johnny Was” or even the Specials’ anti-racism screed “Doesn’t Make It Alright.” Burns made his band’s debt to the Clash explicit after Strummer’s death via the track “Strummerville” on 2003’s Guitar And Drum.

The Specials

“Music gets political when there are new ideas in music,” Specials founder/keyboardist Jerry Dammers told The Guardian in 2008. “Punk was innovative, so was ska, and that was why bands such as the Specials and the Clash could be political.” Indeed, no British band embodied so many of the Clash’s principles as well as the former Coventry Automatics, the name they were called when they toured with them in 1978. For a time, they were managed by Clash manager Bernie Rhodes, though not happily according to 1979 Specials debut single “Gangsters.” But no band this side of the Clash embodied the fusion of reggae’s earliest iteration, peppy early ‘60s ska, with punk guitars and aggression more than the Specials. (In fact, they may have even got an idea or two from the Clash’s ska-tinged remake of Toots And The Maytals’ “Pressure Drop.”) But the Specials’ fervent anti-racism, down to their multi-racial lineup and fierce anthems such as “Doesn’t Make It Alright”? Don’t say Joe, Mick, Paul and Topper didn’t have an effect on them.

Red Rockers

The Clash’s American influence was significant after they came over twice in 1979. “You felt a different way coming out of that gig,” Henry Rollins said of seeing them Feb. 15, 1979 in his native Washington, D.C. “That night I went home and I actually physically threw out… maybe about 25% of my records after I saw the Clash.” This is likely what also happened to New Orleans quartet the Red Rockers. Their 1981 debut full-length, Condition Red, is a great lost American punk classic, featuring 12 aggro-guitar shouters such as “Guns Of Revolution” and “Dead Heroes,” whose songwriting credits you’d swear should read “J. Strummer – M. Jones.” All existing photos, swaggering in spray-painted shirts and tight trousers, could be Clash publicity pics. Condition Red’s sleeve even resembles the Clash’s 1977 debut LP. None of this is a bad thing.

Black Market Baby

“Most definitely,” Black Market Baby vocalist Boyd Farrell affirms when AP asked if the Clash inspired the D.C. punk squad he led from 1980-1988. “I saw them back in 1979 [likely the same Ontario Theatre gig Rollins attended] and said to myself, ‘Now that’s what a band should sound and look like.’” It’s audible in such roaring anthems as “White Boy Funeral” and “Potential Suicide.” It’s also visible in the tough all-for-one/one-for-all unity displayed in promo pics—that same band-as-a-gang vibe the Clash exuded in full effect. They cut a last-gang-in-town swathe through hardcore bands almost 10 years their junior, and still do.

Social Distortion

“I was watching the Clash,” Social Distortion mainman Mike Ness told Alternative Press in 2019. “They dressed up cool. I wanted to be like them…They took pride in showmanship.” Seven years before that, he told Denver alt-weekly Westword, “Maybe we didn’t have quite the global message that the Clash had, but the Clash wanted to reach the world. And that’s what I wanted to do.” Defiant anthems such as “Telling Them” and “It’s The Law” flashed more than a little of “London’s Burning,” and there was Jones’ DNA in Ness’ lead guitar style. Certainly, the Americana roots strains prevalent on London Calling must have given Ness license to bring country and rockabilly into everything he’s done post-Mommy’s Little Monster. But if you want to hear the Clash’s influence on Social Distortion made flesh, dig their 2005 cover of London Calling’s “Death Or Glory” for the Lords Of Dogtown soundtrack.

Billy Bragg

“When I heard the Clash, it swept away all my dreams of playing in a stadium and replaced them with dreams of changing the world by playing very loud, fast songs,” Billy Bragg explained to Entertainment Weekly in 2000. “Now I realize I was naive to think the Clash could change the world by singing about it. But it wasn’t so much their lyrics as what they stood for and the actions they took.” Hence, we see the one-man electric troubadour tirelessly ranting against inequality, racism and division. Then there’s gestures like performing an entire set of Clash songs with the Levellers on Strummer’s birthday in 2004 or his pastiche “Old Clash Fan Fight Song.”

The Pogues

Yes, there was more than a little Clash to the Pogues. The Celtic folk-punks’ leader Shane MacGowan is visible in the audience in several photographs of early Clash gigs and was the “victim” of getting his earlobe “bitten off” that’s become both Clash and MacGowan legend over time. Clearly, the Clash’s gang-like presentation inspired the Pogues. Then there’s also the use of roots material as ballast for such rabble-rousing anthems as “Transmetropolitan” and “Streams Of Whiskey,” as well as MacGowan’s man-of-the-people persona, which is pure Strummer. The connection was cemented with the Clash singer’s frequent strapping-on of his trusty old, battered Telecaster to join the Pogues for Clash oldies such as “I Fought The Law” or “London Calling.” He even deputized on Pogues tours after MacGowan quit.

Manic Street Preachers

“Without them, the Manics would be a completely different band,” Manic Street Preachers singer/guitarist James Dean Bradfield told the NME in 2015. Watching a television retrospective of punk-era footage from the Tony Wilson-hosted So It Goes program gave teenage Bradfield, Nicky Wire, Sean Moore and Richey Edwards their first glimpse of the Clash via typically wired, explosive 1977 footage of “What’s My Name” and “Garageland.” “It was earth-shattering,” Bradfield continued, still awestruck. “Politics looked glamorous for the first time ever.” It factored into their early glam-punk image (white skinny jeans and spray-painted women’s blouses) and man-the-barricades anthems. Even their later paramilitary style echoed the Clash’s Combat Rock era. But if those aren’t obvious signposts, how about frequent live covers of “What’s My Name” or “Train In Vain”?

Green Day

“One thing I can’t do is do anything half-assed,” Billie Joe Armstrong told Rolling Stone in 2013. “I want to make sure everything is right, that the song is fully realized. I think of…the first Clash album—those songs are fully realized, well played. You can almost hear them doing it in a practice room…I want to make sure that while we’re evolving, we still sound like a unit.” The Clash influence on Green Day became blatantly obvious 2004’s politically charged American Idiot: blockade-smashing political anthems decrying the Bush administration, dressed in big Gibson block-chords and matching red-and-black stage outfits festooned with stars. Armstrong, Mike Dirnt and Tré Cool had gone from chronicling generational angst in singsong fashion to registering their dissatisfaction with the powers that be and adopting a heroic stance onstage. And if all this isn’t evidence enough for you of Green Day’s Clash influence, perhaps live renditions of “I Fought The Law” or “Should I Stay Or Should I Go” (as the Coverups) are. Or Armstrong’s one-man COVID-19-era cover of “Police On My Back.”

Rancid

“There’s a rather stupid, obvious comparison,” OG Rancid drummer Brett Reed scoffed in a 1998 article from Pennsylvania newspaper The Morning Call on fourth LP Life Won’t Wait, re: frequent press parallels with the Clash. “We have a very unique sound. I love the Clash, but it’s sophomoric to compare us. They don’t really do two-toned ska or fast punk rock.” Well, they actually did, Brett. And so did Rancid. Your band also covered Clash debut album staple “Cheat” for the tribute album Burning London. And then there’s Tim Armstrong signing Strummer to Hellcat Records and all the London Calling/Sandinista!-like genre-hopping on Life Won’t Wait. The complaint sounds rather disingenuous. Besides, Jones himself gave us his endorsement of Rancid.

U.S. Bombs

“It’s just the old basic stuff that we used to listen to in skate parks, the stuff that still has meaning,” skate legend Duane Peters said to Oklahoma City’s The Oklahoman of his trad-punk group U.S. Bombs in 2000. “The Clash, Stiff Little Fingers, Chelsea, the Ruts, all that old twang.” If it wasn’t apparent in Peters’ soused-Strummer persona or Kerry Martinez’s crashing Les Paul chords that the Clash were their main man, or in their spray-painted stagewear, perhaps the December 2017 release Clash Tribute made it more obvious. Absolutely dead-faithful renditions of “Death Or Glory” and “Straight To Hell” should be all the evidence needed.

Jesse Dayton

“I saw the Clash in San Antonio at the [Majestic] Theater,” latter-day outlaw country singer/guitarist Jesse Dayton remarked to Your Punk Professor in 2019. “That changed my life.” The Beaumont, Texas native—who has scrubbed Telecaster for everyone from Waylon Jennings and Johnny Cash to X, and made horror movies with pal Rob Zombie—learned to weave American roots genres and demon energy into his hard-as-nails honky tonk sound that night. He’s applied it to all of his endeavors since, including transforming the Clash’s reggaefied “Bankrobber” into a Bobby Fuller Four-style Tex-Mex rocker on 2019’s Mixtape Volume 1 covers collection.

The Libertines

It was obvious the moment the Libertines arrived fully formed in the early ‘00s that there was more than a smidge of the Clash to Albion’s greatest musical ambassadors. Guitarist Carl Barat claimed to the NME that his sister babysat Strummer’s kids, and he’d met him as a child. (“It would have been great to meet him when I knew who he was, though.”) Whether this was a tall tale or not, Jones recognized enough of his old band in the deeply romantic skiffle-punks to produce their first two superb LPs and even join them onstage on occasion to fumble through a Clash classic or two. “I think Mick recognized the parallels in mine and Peter [Doherty]’s writing partnership and how a certain way of life manifests itself as a band,” Barat ruminated.

Riverboat Gamblers

Though most look at Austin punks Riverboat Gamblers and instantly think “MC5 fronted by Lux Interior,” it should be obvious that there’s some Clash in their DNA. Though they aren’t political except maybe in the most subtle of ways, their total-assault live presentation and sheer aggression are pure Clash, alongside their willingness to bend the form on later albums like Underneath The Owl. But mostly, what the Gamblers got from the Clash was their usage of guitars. “We think about what two guitars do all the time, mainly because of them,” Ian MacDougall, half of the Gamblers guitar team, tells AP. “Also the mix of Tele and Les Paul.” “Yeah, absolutely,” Fadi El-Assad, the other half of the guitar duo, says of the Clash’s influence. “The back-and-forth, call-and-response guitars I definitely lifted.”

Anti-Flag

“The Clash is definitely our favorite band ever,” Anti-Flag singer Justin Sane huffed during a set of Clash covers at Berlin’s Ramones Museum in 2009. “Billy Bragg said the Clash would not be a political band without Joe Strummer, and Anti-Flag would not be a political band without Joe Strummer.” As if the pulverizing rendition of “Career Opportunities” that followed wasn’t evidence enough, nor the mostly Clash covers Complete Control Sessions EP. But if you don’t hear their fierce social justice anthems and two-guitar attack, ignore their unified look and that frontline charging the stage’s lip and not think “the Clash”? You could stand a cold shot of awareness.