Catherine McGann recalls photographing Harlem drag balls, Eminem and Flea

AP Gallery explores the visual culture of the music we know and love. Each month, we connect with photographers, directors and other creatives who shape music from behind the scenes. With each issue, we explore the stories behind the shoots and take deep dives into the most compelling media, asking about the creative visions as well as the happy accidents that create some of the most powerful moments for your favorite artists.

For issue 400, we connected with photographer Catherine McGann. McGann has had a vibrant and impressive career, shooting a wide range of artists from across the entire musical spectrum. She was a staff photographer at The Village Voice, a legendary newspaper that covered everything from the first years of the punk scene to the rise of hip-hop and beyond. During her years there, McGann worked tirelessly to document the New York underground. She managed to capture the legendary Harlem drag balls, a staple of LGBTQIA+ culture that paved the way for modern drag stars such as RuPaul and Trixie Mattel. She also captured the early years of hip-hop’s meteoric rise to mainstream success, transforming the entire globe in the process.

Read more: 11 LGBTQIA+ punk musicians who changed the genre forever

Since moving to L.A., McGann has continued to be a crucial voice in the world of photography. Many of her photographs have also become important historic documents for capturing a pivotal moment in music history. Her works have appeared in documentaries and other collections, in addition to forming the centerpiece of solo shows and museum exhibits. McGann’s photos have been featured on a number of platforms, including Morrison Hotel Gallery and Getty Images, Sonic Images, Rock Archive. They have also appeared in gallery shows and exhibits such as Grace Before Jones: Camera, Disco, Studio and Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop.

During our conversation, McGann discussed her early years and how she connected with The Voice. She also shared stories about her unique perspective, which was shaped by her love of her city and her careful approach to crafting authentic pictures of her subjects. Along the way, McGann recalled her time shooting the Harlem drag balls, documenting hip-hop legends such as Big Daddy Kane and LL Cool J and working with goth pioneer Diamanda Galás. She also recalled shooting rock icons such as Green Day and Flea, as well as how she came to have one of the earliest photographs of Eminem.

Let’s talk about your work. Through The Voice and elsewhere, you worked with so many incredible artists. One thing I’ve really been wondering about is how you ended up shooting in the Harlem drag ball community.

I cannot take credit for that because there was this writer at The Voice. His name was Donald Suggs. He is the one who said to me, “Hey, Cathy! Do you want to come up with me and do this?” He wrote a big piece for The Voice on that, and I was like, “Yeah, sure, I’m all in!”

I met Donald up there. I think he said, “You’ve got to meet me up in Harlem at midnight.” I remember taking a cab by myself and walking through the door. The best analogy I can give you is that it felt like the scene in The Wizard Of Oz. [It’s] this black-and-white movie, and then they get to Oz, and all of a sudden, it’s color. That’s what it felt like for me. Walking into that room was like, “Wow, this is amazing!”

Read more: Photographer Bob Gruen talks new book and capturing punk’s early days

It was certainly a privilege to be there. It’s obviously a very huge, important thing to that community [who] would look forward to this thing and work super hard to be at those things. I was very aware of the fact that I was an outsider, but everyone there was very generous to me. They worked hard for that look and wanted people to see.

One of the other amazing moments you managed to capture was the early mainstream success of hip-hop. The 1980s saw this incredible flowering of hip-hop. I especially love the shot of LL Cool J at the Run-DMC party. How did you come to connect with that world and shoot artists like him and Big Daddy Kane?

I think that was the same year, 1988. I’m extraordinarily lucky. I was just there, just doing my thing and my job. That night, the LL Cool J picture you [are] talking about, was a party at The Palladium, which was one of the clubs. The Palladium was amazing and was the club. That was a party for Run-DMC’s movie Tougher Than Leather. I had no idea how historic that would be because, seriously, everybody was there. When I tell you everybody was there, everybody was there!

I was just like, “Oh, my God, Spike Lee is here!” “Oh, my God, Flavor Flav is here!” LL was very chill and nice. He was really young in that picture. It was a blast, and in terms of hip-hop for me, I did get it. I have some pictures of Big Daddy Kane. I was very privileged and did a big shoot with him up on the rooftop of Cold Chillin’ Records.

All I can say is that everybody was out in the clubs all the time. Whatever the event was, all these incredible people would just come to these parties. Then the rest of the time during the day, I’d be doing things like this Big Daddy Kane shoot that was also for The Voice. I had no idea that hip-hop would literally be this global phenomenon now.

Since we’re talking about hip-hop, can you tell me about Eminem? You shot a really amazing picture of him very early in his career.

Again, I am so lucky and so stupid because I’ll tell you honestly: If I could go back in time… That night, I didn’t know who Eminem was. It was his first big show in New York at this place called Tramps. I was eight months pregnant. I was not having it, and I remember we’re in this tiny club. I was slammed up against the stage pregnant with my son up against the loudspeaker.

The place was packed. He was right in front of me, but I had to get to another job. I had to get to this other nightclub. I was trapped because they had the police barricades. I was allowed in this tiny space, and then the crowd is pushing forward. I was so pregnant and uncomfortable. I just needed to get out of there, and so I shot it really fast. Part of my brain was not as into it as I should have been, and when I look back at those pictures, I just wish I’d done a better job.

I think that what’s happened is they were the oldest pictures of him that were available for a long time. I’m sure there’s other people out there who knew him and shot him in Detroit. But because he came to New York, those were in the pipeline. I’m very lucky, and I do love him! He’s been great. Some other magazine a couple of years ago talked to me about that when they did a big piece about him, and we’ve connected a couple of times. HBO had done a series about hip-hop, and they used that image as the poster for the series. It was so wild! Life is long and strange is all I can tell you.

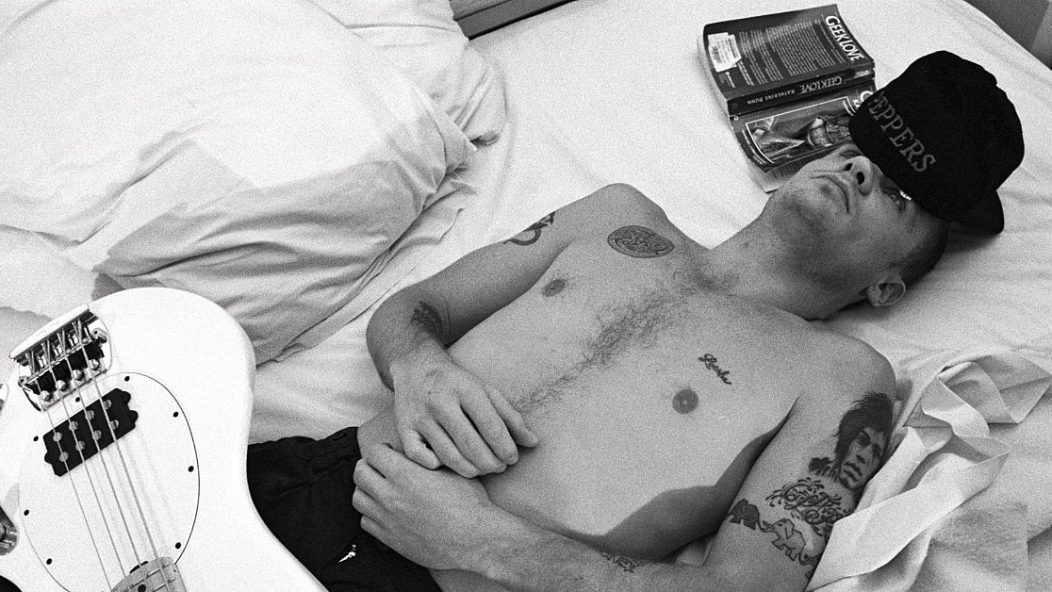

Another great shot you took is of Flea. I can tell it has a great story attached to it.

I used to shoot for Guitar World almost every month for years. There weren’t a lot of women. A lot of times, I felt like I would get the people either on their way up so you hadn’t really heard of them, or you’d get them on their way down. Very rarely would I get somebody who’s at their peak. Flea was a different story. I was thrilled to get this gig! I was really uptight about this job. It was going to be a big story. It was supposed to be Flea and Bootsy Collins together.

I get to the hotel, and I’ve got this friend of mine being an assistant. I think they were like three hours late, which is nothing unusual. The whole day and I think the day before, it was like the story kept changing. Bootsy’s coming. Bootsy’s not coming. You got to think on your feet a lot. I am not somebody who ever had a studio with backdrops. I like a more documentary approach. I would let people be themselves and see what happened.

Read more: 20 songs that transformed punk, from “Raw Power” to “Rebel Girl”

I don’t remember who it was. Probably someone for the record company took pity on us, sitting in the lobby and was like, “Do you want to just go up to his room?” They let us hang out in his hotel room and set things up, set up the lights. He finally comes in. I opened up the door to his room, which I guess is weird. The first thing he says to me is, “Don’t ask me anything. Don’t ask me to do anything. I feel horrible. I have the flu. I just came back from the doctor.” He flops himself down on the bed, and I’m thinking to myself, “You got to be kidding me!” I get to shoot Flea, and every picture of him is like jumping up in the air and naked. I get Flea, and he’s sick. If that’s [what] you’ve got, that’s what you’ve got.

In retrospect, I just might be one of the only photographers who does have that kind of a moment with him. Every other picture of Flea is of him jumping up and down and yucking it up for the camera. I love that, actually. He was reading this book in the picture. I have him at a more intimate moment that is really, really hard to get as a photographer. I would venture to say damn near impossible now.

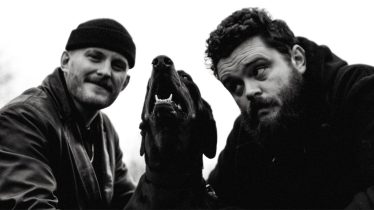

You’ve also had a professional connection to Green Day. You’ve got a bunch of cool images, including that very candid-looking snapshot of them. How did that one come about?

That was very hard because that was at Madison Square Garden. There’s nothing intimate about Madison Square Garden. Green Day were obviously famous enough to have sold out the Garden, but they were, in my mind, new. By the time however old I was in ’94, I was already feeling older than they were.

The way these things work is that you were literally given five minutes backstage. I didn’t have a timer on me, but it was pretty quick. I don’t think I had an assistant with me. If you have all these people hanging around you doing hair and makeup and this and that, it’s not authentic. They came in and were just being young goofballs and not being terribly nice to me. They weren’t horrible; they just didn’t care. They were young guys who sold out the Garden, and who am I? I’m like a geek. I pull this chair over to stand on to get higher. The stupid chair collapses on me, and I fall. That’s what got them to laugh. I was fine and just went with it. It lightened up the atmosphere. It just made me look like more of the geek that I really was.

The picture where they’re asleep. That was the picture to me. I turn around, I get to the door and I looked around, and that was what they did immediately on their own. They’re lying there hugging their teddy bears like little boys, which is really what they were. I hadn’t packed away that one camera. That’s the kind of moment that I love. It’s really hard to get. As a photographer, I have to say those things are given to you. You can’t really plan on them. Sometimes you just get it. Sometimes you don’t.

One of your other shots that I really love is of Diamanda Galás. She’s such an icon, musically and visually. What’s the story there?

Again, early into The Voice, I was given the assignment to photograph her. I did a little bit of research. If you’ve seen that cover, it’s scary! I got all this crazy film and was like, “I’m going to take her to the graveyard out in Brooklyn.” They gave me a little bit of a budget. I don’t know where The Voice actually got the money. I got infrared film and infrared color film; I still have rolls in my closet.

That whole day was wild. I lived in the East Village at the time, and she lived not too far away from where I was. She’s like, “Oh, I’ll just come to your house!” I opened the door to my apartment, and she is this sunny, bouncy, super-sweet person from San Diego. She goes in my bathroom to do her makeup and hair and comes out another person.

We took a cab out to where that graveyard is, and I loved every second of it! I’m using all these special cameras. One of the images I sent you is this process called reticulation where you basically freeze and burn the films so it cracks. I wanted to make it look like something special for her because of what her music was like and because she’d done Plague Mass, which was about AIDS. Her brother had died from AIDS.

Read more: The 15 best punk albums of 2002, from Sleater-Kinney to the Used

To me, that was just genius! She came to my house afterwards. She was like, “I want to come and see what they’re like.” I don’t really do that [for] anybody else, [but she] came to my place and approved the ones that she liked. But we got along so well after that she used me a lot. I ended up photographing her a number of times.

You can read the whole interview in issue 400, available here.