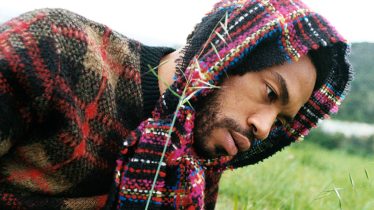

Dear Jack: Andrew McMahon talks about the film chronicling his battle with cancer

On the same day in 2005 that ANDREW McMAHON finished mastering Everything In Transit, the debut from the Something Corporate frontman’s solo project JACK’S MANNEQUIN, he was admitted into the hospital for the beginning of what would be a battle against acute lymphoblastic leukemia. During the months prior, he had started documenting the creation of the album with a video camera given to him by his record label, and as his story took a heartbreaking and unexpected turn, McMahon kept the camera rolling. He didn’t know what the footage would be used for or if anyone would ever even see it. But over the course of his fight with cancer–including radiation and all of the horrors that came with his illness–the camera became something that McMahon clung to as his own personal way of coping. Later in the year, on the same day he received a bone marrow transplant from his sister Katie, Everything In Transit was released, and McMahon subsequently reached a full recovery. At the urging of friends, he decided to use the footage he had shot for a movie, DEAR JACK, which–after three years of work–was released earlier this week. We caught up with the eternally upbeat and positive McMahon who, unsurprisingly, sees this unflinchingly personal view into his life as something that isn’t really about him at all.

INTERVIEW: Tim Karan

At what point during your experience did you decide to videotape your journey?

It wasn’t really a conscious choice, it was sort of a continuation of what I had already been doing. When I signed with Maverick in late 2004, eight or nine months before this had even happened, they gave me a video camera with the caveat of, “Hey, we’ll give you this camera if you can sort of shoot some B-roll footage around the studio and we’ll include it with the album or on a DVD or whatever.” But it happened during this very interesting period of my life. I was stepping away from Something Corporate and starting down the road with my new project Jack’s Mannequin. I had also just been separated from my girlfriend at the time, and all of these factors just compelled me to film. I wasn’t sure that I was ever going to put it out, but it was a unique enough period of my life, and I had this camera and I was already doing all these other sorts of projects like drawing and journaling. The video camera sort of became the thread that tied it all together. I would regularly check-in with the camera and say, “This is what I did today” even if it was just me going to parties with my friends or going to the studio for Jack’s Mannequin rehearsals. When I got sick on that first tour, they put me in the hospital and I remember calling my manager and saying, “I need you to bring my video camera.” That’s sort of where it all began. That first night, I filmed one of the scenes you see towards the beginning where I say, “Hi, I’m Andrew McMahon. I play for two bands.” That scene was either the first night I was in there or the night I was diagnosed. I never really looked back after that.

You never thought for a moment that maybe it was all too personal to record?

Ironically, a lot of the reason that I got the camera out wasn’t because I wanted to document anything, but it was because it was a way for me to say the things that I didn’t want to say to people. It was strange that I would choose pretty much the most public forum you can imagine, but I would use the video camera during my treatment in the same way that I used my journals. It was a way to get the thoughts out of my head and put them down and not necessarily have to inundate the people around me with all the little details I was going through. It wasn’t until later until [producer, Mae drummer] Jacob Marshall and [executive producer] Brett Brownell–two dudes I knew from traveling with the band Mae–approached me because they had seen some of the footage and said, “We think this would be powerful to share with people.” That’s kind of how it all ended up being seen. But from where I was, I didn’t think about turning the camera off because, at that point, I didn’t know if anyone would ever see any of it.

As you were filming, did you ever go back and watch the tapes and delete anything?

Nah, it was very haphazard at best. I’d put in a tape and throughout whatever was going on, I’d just film or ask people around me to if I couldn’t. Then I threw all the tapes in a drawer at wherever I was at the time. When the guys approached me about making it into a film, I opened up the desk drawer next to my bed and it was just filled with tapes, and I said, “Well, here it is.” [Laughs.] But, no, nothing ever got erased. It was just thrown out there and put away until somebody asked me to see them.

How much footage did you have?

Between the first six months all the way up until the show that’s at the end of the movie, I think I had somewhere between 60 to 100 hours of tape. A lot of the time I’d just leave it running and shoot the shit, you know? [Laughs.] A lot of the times–for example, there’s a shot in the hospital where I’m talking to [my wife] Kelly–the tape probably ran for an hour. I’d just sit it on the tray they’d put my dinner on and we’d just talk. That’s where you get a lot more of the intimate moments–the camera was on for so long that you almost forget it’s there.

Everyone around you–your family and hospital workers–were okay with that?

Yeah, I think it was really evident to people that it had become sort of an extension of myself and my art. When you get into that position, the reality is that if people see that you’re attached to something, they tend to embrace it. I definitely had a couple of times–there’s a scene where I have a spinal tap–where I had a friend shoot and they just didn’t want to. But I was like, “Dude, this is for me.”

When did it become a reality that you were going to actually turn this into a movie for others?

I joke that it actually wasn’t until about four or five months ago. [Laughs.] The first time it was brought up to me was probably 2006. I was still recovering. Jacob and Brett cataloged the footage for me and then, ultimately, we found our friends [directors] Corey Moss and Josh Morrisroe who came in to do the edit. But it’s been a process. It took the better part of three years.

How involved were you in that process?

I was increasingly more involved as we got closer and closer. I set up a bit of a structure around the idea that if we were gonna do this movie, I was going to need to rely on a handful of people who are really close to me to watch it and give notes. I just knew that instinctually I probably wouldn’t be able to be objective about it. When you watch yourself on film, you can almost start giving notes that come from a place of vanity instead of what’s best for the story. I really wanted it to be as raw and honest as possible, and that meant keeping a lot things where I didn’t look good. [Laughs.] I saw the first cut sometime in mid-2006, and I woke up the next day feeling like I was 100 percent sick again. It triggered a muscle memory in me and, in turn, I made the decision that I couldn’t really be involved and watch this over and over and over again. About every three to six months, there’d be a new edit, and I would sit down and watch it and give notes. But I had people from my record company and management and others who would weigh in, too. Finally, about five or six months ago, I think I got enough distance from it all and I was able to work on the final cut with Corey and Josh.

What did it feel like at the time as you watched the very first cut?

It was painful. The first cut we saw wasn’t really structured as a movie as much as it was a catalog of footage. We basically went through about two hours of footage from the hospital. It was brutal. I didn’t know it would be so hard, and that’s why I think it took so long to get the right edit. I needed to try to see it as a story and see it as a movie and not see it as my memory.

Are there any parts that are still especially difficult for you to watch?

One shot that’s rough every time I see it is a scene toward the end where you see me kind of lying down on a gurney where they’re taping me against a wall for radiation. I don’t know why, but for some reason it seems like the shot in the movie where I seem the most vulnerable.

What would you like for people to take away from the film?

It’s funny because my goals have sort have changed and mutated over time as I’ve come to know the movie a little bit more. I think the thing I’m most proud of about the movie is that this is a very real, first-person perspective on being stuck in the hospital and what goes into it. If nothing else, I hope people take away that this is a very honest and truthful and raw look at this period of time in somebody’s life. Beyond that, the goal is that hopefully patients and survivors and families who have been touched by this disease will find something to be able to relate back to and have sort of a shared experience. While there is no roadmap for it, we all share kind of a similar experience. And then, of course, for people who haven’t experienced it, I hope they can draw some hope from it. As hard as things can be and as derailed as you can become during your life, you can get to the other side of it. alt