Everybody (Still) Hurts: The story behind the ‘Essential Guide To Emo Culture’ 10 years later

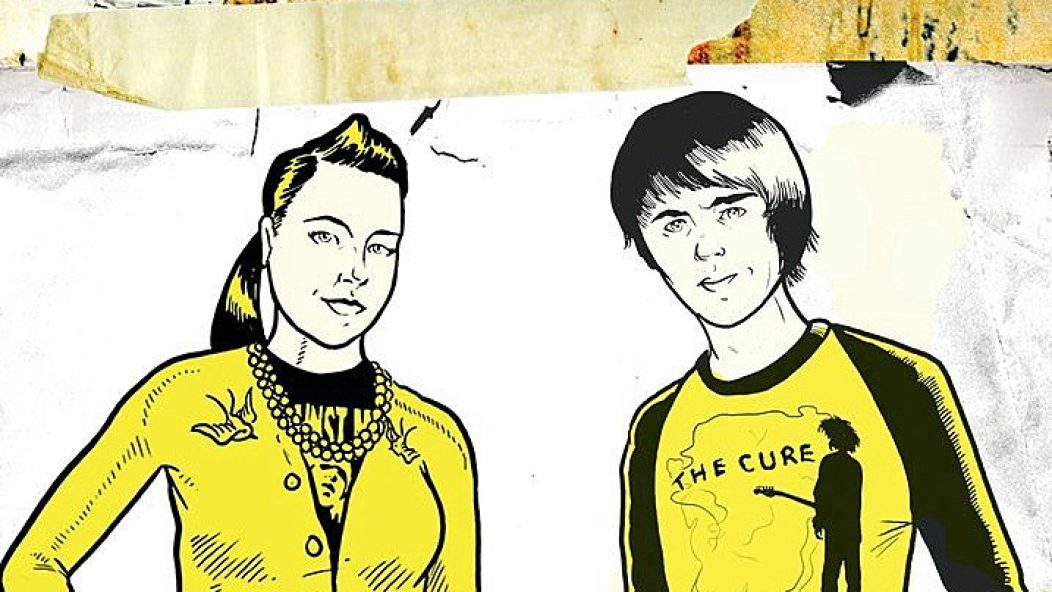

In mid-2000s, a cultural phenomenon took the world by storm. Fueled by heartfelt and confessional music, painted-on jeans, too much black eyeliner and swoopy bangs that had been flat ironed to Hell, the emo subculture quickly took over America’s suburbs (and beyond). As emo took over the mainstream, many people not installed in the scene passed it off as “just a phase.” While others were dismissing the blossoming emo culture’s validity, two of the scene’s most established scribes were writing its guide book. Filled with everything from emo schools of thought to their habits, style, icons and their attendant history, Everybody Hurts: An Essential Guide To Emo Culture offered a hilarious and informative inside look at what it meant to be emo. But to fully appreciate this magnificent piece of literature, which should be considered essential reading (even Dashboard Confessional’s Chris Carrabba says so) for misfits everywhere, you first have to understand where it came from.

During the height of emo, Leslie Simon and Trevor Kelley both worked for Alternative Press. Simon served as an editor at AP’s headquarters in Cleveland, Ohio, and Kelley frequently contributed as a staff writer working from California. And while the both of their bylines frequented the pages of the magazine, their paths didn’t cross much until the summer of 2004 when they first met face-to-face. Kelley and a friend were moving across the country to New York and made a stop in Cleveland to stay with Kelley’s father, visit AP HQ and catch a show at one of Cleveland’s punk venues. And though Simon had met Kelley earlier in the day at the office, his face just didn’t register when she saw him again at the venue. “It was a very hot summer day, and I was feeling like a wilted piece of lettuce in the Grog Shop, hanging out in the back, and here comes this guy in shorts, flip-flops, I think a collared shirt, a hat, drinking a glass of merlot in a real wine glass,” Simon recalls. “He walked over to me, and I was like, ‘Who the fuck are you right now?’ Like, this is going against every single concert rule that you’re trained to do: You’re not wearing closed-toed shoes, you’re a man wearing short-shorts, you’re drinking merlot in the summertime, which isn’t even refreshing—I mean, he looked like a cartoon character.”

It wasn’t until later, when Simon took a work trip to New York and attended a dinner with Kelley (and many others who worked throughout the scene), that she really got to know the punk-rock writer with a startling amount of swagger. “At that dinner, Trevor and I talked more, and I realized that he wasn’t a total creep,” she says, laughing. During that time, Simon made frequent trips to NYC and the pair quickly became close friends, having marathon hangs where they would start at lunch, walk around the city, grab dinner, go to a show and then hit an afterparty. “We did all these things together and just got to be really great friends,” she says. “Just very simpatico people doing the same stuff. Like writing and really caring about the writing and caring about the people we were writing about.”

And like many writers, Simon had the goal of one day publishing a book. “Our colleagues and friends and peers were starting to get book deals, and being the competitive little bugger that I was, I was like, ‘Oh, you got a book deal? I gotta get a book deal,’” she says, laughing. “I was coming up with a lot of ideas that I thought were great. I would tell my roommate at the time, and she’d be like, ‘Umm, I don’t think that’s it.’ And I would just be like, ‘Okay, note taken.” Then it came to her: She remembered a book her parents had that fascinated her while she was growing up called The Preppy Handbook. “It was a very tongue-in-cheek, half-illustrated, half-prose book about the insurgence of the preppy generation,” she shares. “Where did they go school? How did they dress? What did they listen to? And it just struck me one day, that with emo still being a little bit of an uncharted territory for the mainstream, that it could use a handbook to guide people through what it is, what it isn’t, how to spot it, what does the culture mean? And I told my roommate, waiting for her to say that’s a terrible idea, and she was like, ‘That’s it, that’s your idea.’”

Simon met with an agent in New York to pitch her idea, and they loved it. “However, they did say that they worried that I wouldn't be able to represent a male voice, and they wanted an even gender approach to the book,” she recalls. “At the time, being really green and just seeing a book deal on the table, I was like, ‘Yeah, totally, that’s great—right, yeah, I don’t know if I can write male.’ I don’t know what ‘writing male’ is, and frankly I’d been so snarky at the time, I think I could have—if I had said my name was Joe on the page, you wouldn’t have doubted it.” Regardless, she immediately knew what to do. “There was like no hesitation in my head—I said, ‘Okay, let me see what I can do, I’ll figure it out.’ I was out in Midtown, I walked out of their office, I called Trevor on the phone and I think I just said, ‘Do you wanna write a book?’”

The two spent the next three to four months as anthropologists of emo, documenting everything from beliefs and history to eating habits and essential records, with plenty of helpful tips along the way (For example, when it comes to fashion: “DO layer. Nothing says emo like a cardigan over a hoodie over a tank top over a T-shirt. Just like the layers of an onion, the more clothing you can peel off, the deeper you are.” “DON'T put on a band's T-shirt immediately after you buy it at the merch table. The maneuver screams emo amateur. Instead, if you're a girl, shove the shirt in your tote bag, and if you're a guy, stuff it into the back of your pants so it hangs like a tail. Acting like you don't care is essential.”) Kelley even stayed in Cleveland for part of the writing process and the two would stay up late writing at the table in Simon’s apartment, bouncing around ideas and trying to make each other laugh. “I would go to AP during the day and work, come back from like 7 to 11, do more work, and then on the weekend do work. But I never thought of it as ‘work,’” she says. “I would tell people I couldn’t see them or I couldn’t do things, but I never felt like I was missing out on something, because what we were doing was so special and also, who gets to do this? This is crazy.”

|

|

The book was published in April of 2007 and essentially became the encyclopedia of all things emo. While it is certainly entertaining and full of wisecracks and nuances that only insiders will understand, the book is, above all, educational. Simon and Kelley might have been a couple of smartasses, but they were smartasses who knew that emo was more than a haircut and some makeup. And though some of the references might show its age (you’re probably not checking your Myspace profile on your Sidekick anymore), like emo itself, Everybody Hurts has stood the test of time, providing not only a snapshot of emo in the mid-2000s, but a timeless definition of what emo culture is all about: the music and community.

“A lot of people, mostly critics and Pitchfork disciples, were quick to write off emo as a passing trend. They thought it was a gateway music that would provide an adequately angsty soundtrack to your teen years. Then, after puberty passed, you'd throw away the eyeliner, hide the flat irons, and try to forget whether mics were for singing or for swinging,” Simon says.

“But emo wasn't a footnote. It wasn't even a chapter. It's a book… and chapters are still being written with every passing year. The music might change slightly, but the fans remain the same, and they keep listening because misery always sounds better with a melody.”

We know you're dying to read (or reread) this book. You can pick up a copy here.