Exclusive Interview: Pete Wentz on Black Cards, fatherhood and Patrick Stump

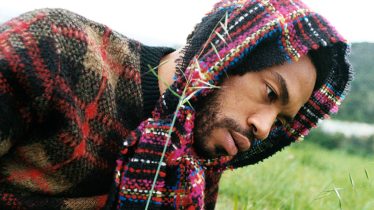

(photo by Dan Newman)

In a sense, Pete Wentz’s musical career has always been anchored by relationships—whether these come in the form of platonic creative collaborations (Fall Out Boy bandmate Patrick Stump) or in the form of romance-as-lyrical-fodder (see also: Fall Out Boy). With his new group, Black Cards, who are being featured in AP #277, relationships of another sort play a part: the convergence of musical genres and styles. In this exclusive interview, Wentz expounds on the musical lineage of Black Cards, reveals how fatherhood has affected his music and clarifies the status of his friendship with Stump.

Interview: Ryan J. Downey

Tell me about the convergence of old reggae with electro-dance music in Black Cards.

My mom, my family, is from Jamaica. I grew up going there a lot. I didn’t appreciate then that while Bob Marley and the Wailers are cool, it goes much deeper than that. I’ve watched people when their bands are on hiatus or whatever it is, and they have the itch to do something, but they don’t really do anything that differently. It makes it all the more easy for people to be like, “Well, why doesn’t he just do his [main] band, then?” This was a chance to do something I listen to, which people probably won’t see coming, but that’s really authentic to the ideas I have and music that I listen to when I’m with my kid.

The idea was to clash that against the Tom Tom Club or Lily Allen, or British electronic music: Sam [Hollander] and I tried it on a couple of songs and it just didn’t work. But then there was the song “Summer Nights,” which was the perfect combination. As we’ve gone, we’ve realized more what the sound was. We were talking one day and I was just like, ‘Well, what is this album?’ And Sam was like, “It’s a vibe album. Essentially, you were a guy in a pop-punk band, and you made a pop album that’s like hanging out in the islands and smoking weed,” or whatever. [Laughs.] I would have never predicted that in a thousand years, but it’s something I’m really happy to have done and to be a part of.

Pop has never really been that guilty of a pleasure for me, so it’s cool to make it and play it. I think it’s surprising to some people: Bebe [Rexha, Black Cards vocalist] and I were driving to the studio the other day and she was like, ‘What are we listening to?’ I was like, “This is my iPod.” It was all hip-hop and pop music. She was like, “This is so weird.” People assume that the kind of music you’re playing [in a band] is the only kind of music you listen to.

How has fatherhood changed your approach to songwriting and your career?

Being a parent informs whatever art you’re making in a way you’d never even know. You never stop to think that you’re going to spend every waking, breathing moment in some way thinking about your kid. Obviously, it influences the things you do in these kind of microwaves. All of a sudden, different things become cool. Like, “Oh, it’d be really cool to go on Yo Gabba Gabba! or Sesame Street.” You want to do all of these things all of a sudden.

Having a child has definitely taught me patience on a whole new level, which is a really important lesson for me to have learned in life. I don’t know what my threshold was before, I’m not even really sure. But I realize that everything else isn’t so important. At times when I would find myself being, like, “Ugh, why can’t they just get the Starbucks faster!” now, I’ll just sit back and wait. It’s a really good thing for me to have learned. In this industry, you can definitely get caught up in thinking you are the most important person, no matter what.

Many great rock partnerships—Lennon and McCartney, Jagger-Richards—have done work apart, but there’s something special about what they do together. I asked Patrick Stump this question, as well. Are you two forever intertwined because of that special chemistry you have as collaborators?

Yeah. I mean, I think so. In the way that, I mean, I’ve never really communicated with somebody in a creative way the way I have with Patrick. That, definitely over the years, has grown and changed. We’ve gotten to know each other, what irritates each other and how to not do it—and sometimes how to irritate each other on purpose.

One of the greatest things about having the space and the freedom to focus on our own things is that we’ve rekindled the friendship just for the sake of friendship. That’s really important to me. He came over to my house for Easter and we did the Easter egg hunt. When you have a kid, you want your closest friends to be involved in his or her life.

But yeah, I do think we’re forever kind of connected, and we’re kind of kindred spirits as far as that goes. He’s always the person I can still call, and he just gets it. It’s weird, because he doesn’t have to insert anything into what I’m saying to him or whatever. It’s great to be able to have had the breadth [of experience] that we’ve had, because I think I’m able to enjoy what he’s doing on his own now. If we had kept doing Fall Out Boy while it was happening—or if I hadn’t done anything at all myself—I don’t know if I would have been able to truly been like, “Here’s my friend who is doing what he’s been wanting to do for five years, on his own terms, and he’s doing it really well.”

And that’s another one of these lessons. It’s a shame, because you don’t get a lot of these lessons and ideas until you’ve kind of grown up a little bit. I would’ve liked to have applied some of them when I was 22, but it just doesn’t happen. You have to go through that stuff in order to become the person you are later on.