Frank Iero opens up on ‘Parachutes’—”I felt totally emptied but so inspired by the end of it”

Editor's note: This interview was done before October 13 when a tragic traffic accident between Frank Iero And The Patience's tour van and a bus left two members of the band's crew seriously injured. Since then, the band has cancelled all remaining 2016 dates. We still felt it was important to tell Iero's story about the making of the record. Here is that story.

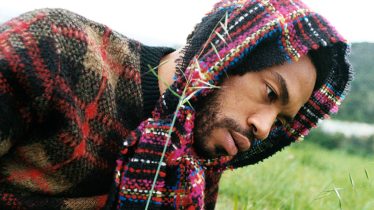

No matter who you are, there are a few things that will always stick with you if you grew up in New Jersey. After being part of a band that reshaped rock music for the millennial generation, Frank Iero still feels most comfortable being interviewed as a “mall rat” (his words). It was in this familiar setting that the vocalist/guitarist spoke in hushed tones of his past, his beginnings as a solo artist and where he is right now on his latest record, Parachutes.

After My Chemical Romance broke up, Iero didn’t think he would return to music. Instead, he had a rather whimsical and uncharacteristic vision of what his new path would be.

“I had this really weird plan,” Iero shares. “I wanted to be a mailman. I said this before, but I think people think I’m kidding, but I really wanted to be a mailman.”

The idea of an internationally recognizable rock icon going door-to-door delivering letters is admittedly laughable. So, after being part of Platinum-selling records Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge and The Black Parade, why was carrying mail his new dream job?

“There’s something romantic about going out and delivering this mail,” he explains, “and when your bag is done at the end of the day, you go home and it’s over and you don’t fuckin’ think about mail again until the next day. When you complete that task, that’s it.” The role could not be more different than the one he played for so many years in MCR. Unlike many other professions, people in the music industry—especially the artists—never really have a day off. Iero was justifiably tired after years of traveling the globe, but in the end, rest wasn’t an option for him either, and music called him back.

“It’s taken me a long time,” he says, “but I realized that creative life is part of who I am, it’s not just what I do, and if I can’t have that, then I can’t be the person, the father, the husband I want to be. I realized that I had to give it a shot, and now here I am years later with another record and I’m actually having a lot of fun with it.” His career as a mailman never did transpire: instead, he started a digital hardcore project (Death Spells, with longtime friend/musical foil James Dewees), got a record deal for his first solo release (Stomachaches) and now, a couple years later ,finds himself sitting in a mall in his home state of New Jersey talking about his sophomore record, Parachutes, to be released under the moniker of Frank Iero And The Patience.

The new record marks a change in both name and attitude for the guitarist-turned-frontman. First known as frnkiero andthe cellabration, the songwriter came to reevaluate himself and his perceptions of what it means to be the lead figure in a band. He admits that, for a while, he felt uncomfortable in his new position, as he didn’t think he could do an adequate job.

“I can’t high kick,” he blurts out, having often viewed this as a mandatory skill for commanding an audience, “but I’m okay with that now. I started thinking about how I could do things a little bit differently, on my own terms, and how I started to see my role as a frontman or a solo artist a lot differently over the past year and a half. I started to get a little less worried about writing a follow-up and things just started to flow.”

That was, until he got into the studio with producing legend Ross Robinson (Glassjaw, Blood Brothers, the Cure). There, Iero hit a patch of emotional turbulence for which he wasn't sure he was prepared.

“Going into the recording process and being in bands, [Robinson’s] name came up every time. We’d go back to these stories about how he did all these things in the studio that made people really uncomfortable or put them on the spot, and it seemed to me through these stories that he was this really aggressive, imposing figure. I didn’t know if I could perform under that kind of pressure. Finally, down the road, I wrote these songs that demanded to be pushed. The first record, when I wrote the songs, I knew that they needed to sound like you were listening in on somebody in a room making these songs, and I knew [Parachutes] needed to be so far beyond that. I needed to be pushed beyond that and possibly even over the edge, and if anybody could do that, it would be Ross.”

During the intensive 17-day recording session, Iero and his bandmates tracked 12 songs under the guidance of what Robinson affectionately calls “mental surgery.” While it doesn’t involve a scalpel, it certainly doesn’t leave the subject unscathed.

“I’ve never had someone work with me in this way,” Iero reflects, “where he puts you all in a room and you’re all tracking at the same time. Usually, it’s all split up—drums get tracked, et cetera. But he likes it all live, and I do, too. So, he has you all in a room, you’re singing in the same room so everything is kind of bleeding into every other mic. He has you play the song a couple of times and then he stops you and then you talk about the song and what it means and where it stems from. I started the process thinking I knew where certain things were coming from and what the songs were about, and I found out later on that they were actually about something a lot different… You start to go down the line and get to the root of why you react to certain things and why things are certain triggers for you. It’s like therapy.”

I felt totally emptied but so inspired by the end of it. It was physically and emotionally like someone had bled me out.

This highly invasive yet deeply enriching method of working with musicians is what Iero believes produced the best possible result for him and his bandmates. As he sits in his chair explaining the whole process, he emanates a sense of tranquility and acceptance that comes from someone who obviously feels bettered by the experience.

“You’re in the room with everybody else in the band and they’re staring at you and you can either clam up or you can open up and get to the root of what’s going on and figure things out about yourself. There wasn’t a day that went by that he didn't make—me, especially—crack. I felt totally emptied but so inspired by the end of it. It was physically and emotionally like someone had bled me out.”

Given the subject matter of some of the songs, it’s no wonder Iero came out of the studio feeling the way he did. He confesses that the final track on Parachutes, “9-6-15,” was the most difficult to sort through because it was written for his grandfather and titled after the date of his death.

When I got into the studio and then once I started to track it…I saved it for the last song because I knew I couldn’t do it [first]. I don’t know how I got through it, but I finally did. I don’t know how I’ll ever do it again, to be honest.

“I knew I couldn’t write a record called Parachutes—these life-changing or life-saving devices—without him, because he was everything [to me]. It took me a month and a half to sit down and write. I finally got through the writing of it and then it changed again, of course, when I got into the studio and then once I started to track it…I saved it for the last song because I knew I couldn’t do it [first]. I don’t know how I got through it, but I finally did. I don’t know how I’ll ever do it again, to be honest.”

Others, such as the single “I’m A Mess,” the opening track “World Destroyer” and “Viva Indifference” wrestle with the idea that the worst moments in life aren’t necessarily bad. To help support this claim, Iero’s brought some evidence with him. He sorts through old photos he has on hand and points to one with a bouquet of delicate white flowers covering a grave. “[These are] at the cemetery where my great-grandmother is buried,” he says. “To me, this is reminiscent about the song ‘Viva Indifference.’ I always thought, ‘How great would it be if we didn’t care as much?’ If we didn’t love or hate or worry, if we just were always on this thin line of indifference. That song takes that idea…that even the things that bring you pain are sometimes the best thing for you. The end of the song is kind of like, ‘You’ve shown me how to love, how to hate, how to experience these things; it’s all your fault and now I’m better off for it.’” In the same vein, his explication for “I’m A Mess” is, “the best things about you are the things that are fucked up, because nobody else can be fucked up like you.”

Iero continues to thumb through old memories and comes across a photo of a 1992 Hyundai taillight. He stops and ponders it, but decides this is a story he’ll keep secret. Tying it into “World Destroyer,” he says, “Maybe I’m not proud of those moments, but all we are is an amalgamation of these experiences, so you can either choose to be beaten down by those and be a slave to them or you can learn how to get back up and realize that this happened so you can learn from it.”

Taking stock of all these memories, he comes to the sobering conclusion that ultimately made Parachutes a reality. “We’re all going to reach the ground,” he says bluntly. “It’s really the journey or the fall and how much we can fit in and take along with us, these collections of moments. What can you grasp onto, what can you latch onto at the end of that quintessential day when you’re on that deathbed or stuck in a hospital somewhere? Are you thinking about the deadlines you hit? Are you thinking about how you don’t remember any of it at all? Or even those stupid little moments…”

As for the big MCR moments fans might think he would have memorialized already, Iero insists he hasn’t given those moments much thought. “I have Tupperware bins full of plaques and stuff in my attic that I probably will never open until either I die or stop playing. I hope maybe my kids will go up there one day and check them out. Maybe they’ll think it’s cool. But we [as a band] always talked about that. You don’t hang up your stuff until it’s done. The trophies don’t mean anything until it’s over. If you don’t feel like it’s over, then you don’t have room in your life for trophies.” As it turns out—and with apologies to the USPS—music is far from done with him. alt

Frank Iero contributed words and photos about 'Parachutes' in the next issue of Alternative Press out on stands November 4. The record goes on sale this Friday.