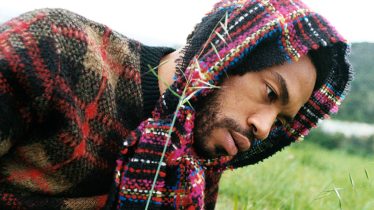

“It’s healthy for a band to become slightly less relevant” – Max Bemis on Say Anything’s new album

Say Anything’s new album Hebrews covers a variety of topics from fatherhood and self-doubt to finding your religion. But if there’s one theme that prevails it’s growing up, both musically and personally. After more than a decade as the frontman and brainchild of Say Anything, Max Bemis was bound to be bombarded with claims from supposed fans that he’s “lost his touch,” implying that because he’s now a family man and not the mentally unstable twentysomething who wrote …Is A Real Boy, his music is somehow less powerful. However, Hebrews proves that despite what the internet trolls have said, Bemis is still able to churn out deeply personal (sometimes uncomfortably so) songs about love, self-worth and his own neuroses. He might have figured out how to handle his bipolar disorder, but that doesn’t mean he’s figured everything out—far from it, as he’ll tell you. In this interview, Bemis discusses all things Hebrews, from the lyrical content and guest vocalists to his decision not to use any guitars on the album.

On Hebrews there are new—maybe not as “edgy”—but still new problems that you have to deal with. You sing about worrying that your wife will leave you or that you won’t be a good father. There are these deep-seated issues that are just as relevant as singing about mental illness.

Mental illness was kind of not the hardest thing for me to deal with as much as it would surprise people. I found out I was bipolar; I had a couple years where it was hard to come to grips with it and stop doing drugs. I was never in a habit, as much as it seems like I was in my music. I just smoked a lot of weed, did the occasional hard drug. I actually got through that quicker than the demons that I’m [dealing with now]. Those demons are still plaguing me, even after I wrote the record, and those are things that have been plaguing me since I was 12 years old. I actually think the stuff I end up suffering from now is a lot more deep-seated than just like, “I have to take a pill so I don’t flip out” or “I have to not smoke weed.” I’m not diminishing that it was a hard time, but it was an easier fix to me than the existential “you’ve gotta be okay with yourself. You’ve gotta be okay to be a father.”

Do you worry about losing touch and not being able to maintain relevancy?

Oh yeah, huge fear. There are two songs [on the record] that deal with it. The first song is “Judas Decapitation,” and that one’s all about my impotent struggle with this insecurity about being angry with these people. I have to express my total rage that there are people who feel the need to say that about me. And then “Lost My Touch” is about accepting it and saying, “This happens to everyone.” It’s kind of the circle of life. You’re the most edgy thing around, and then no matter what over time—you look at a band like U2, and when they first came out they were political, they were edgy, and now when you think of U2 you’re like, “These are the most cushy, diva, over-the-hill”—you know what I mean?

I feel like it’s actually healthy for a band to become slightly less relevant and slightly less edgy. And the song, on an existential level, is really about passing the torch to the people who feel like they can do something edgy and better. And they deserve it. They’re young; I’ve already lived that. I don’t need to live that as a 30-year-old guy. Having a kid really did open my eyes. Being the coolest or the most edgy or the most punk-rock [person] should not be your priority for your entire life. There’s a time and a place for that, and then you have to give your love over to other people and hope they do something cool with it. No one’s a messiah on their own.

What made you decide not to include any guitars on the album?

It was an idea [producer] Tim O’Heir had that I ran with. It resonated with me when he made the suggestion to make an orchestral record. I didn’t want to get rid of the drums or bass; I still wanted it to be rockin’, but it actually opened me up to thousands of possibilities of songwriting and production. I was able to write and arrange the record all on my own on the computer and then have someone else play the instruments, which is actually easier and more conducive to experimentation than it is to make a guitar-rock record. If you do that with guitars, it sounds fixed if you’re using a computer too much with guitars. But if you’re using a computer to map out notes that will later be played by a string section, you can do things that sound really weird. I was able to sit in my own living and aimlessly tinker with these songs, and it was the most fun I’ve had working on music since I was a kid.

Do you think this is the most musical Say Anything album?

I hope so. There’s definitely a lot going on. One thing I think people tend to overlook about our music is how musical most of the records are. I spend a lot of time just trying to do interesting stuff. There’s lots of ear candy on all the records, except for maybe the first one [Baseball]. I think it’s the most traditionally musical because of the strings and because of all the keyboards and the harp and the fiddle… You can really hear it more.

How are you going to convey that on tour?

For the first tour, I don’t imagine we’ll play too many new songs; we’ll probably play four to five. Because it’s only a small part of the set, I figured it’d be cool to experiment and transpose the songs to guitar and to keyboard. The songs are still going to come across the same way they do on the record except without heavy string use. We’re tentatively planning to do a tour at some point with a full string section.

How did you pick the guest vocalists? Did you have people in mind you wanted or did you write the songs and then choose the people?

I wrote the songs first, and there were a lot of parts I assumed I would be singing. There were a couple people I knew I wanted to sing on the record, and I thought it would end with one or two guest appearances. Once I accumulated three or four I was like, “Okay, this is gonna be one of those things.” I started asking friends and people in bands I admired, and it just became fun. It was less stressful than In Defense Of The Genre because I didn’t set out to do it; it just happened.

Is the song “Boyd” named after your father-in-law?

It is, and the reason I named it after him is he has four daughters. The song is about being an overly protective parent. He is not overly protective, but he had to go through this process of seeing his daughters grow up and find boyfriends and husbands. I have a one-and-a-half-year-old daughter, and it was kind of me imagining—or even right now—if anyone were to hurt her, let alone a suitor, I would kill them. I would totally torture them and kill them. So it’s about protecting the people you love, and I thought it would be funny to name it “Boyd” just because he’s not protective, but he’s had to go through that emotional experience so many times.

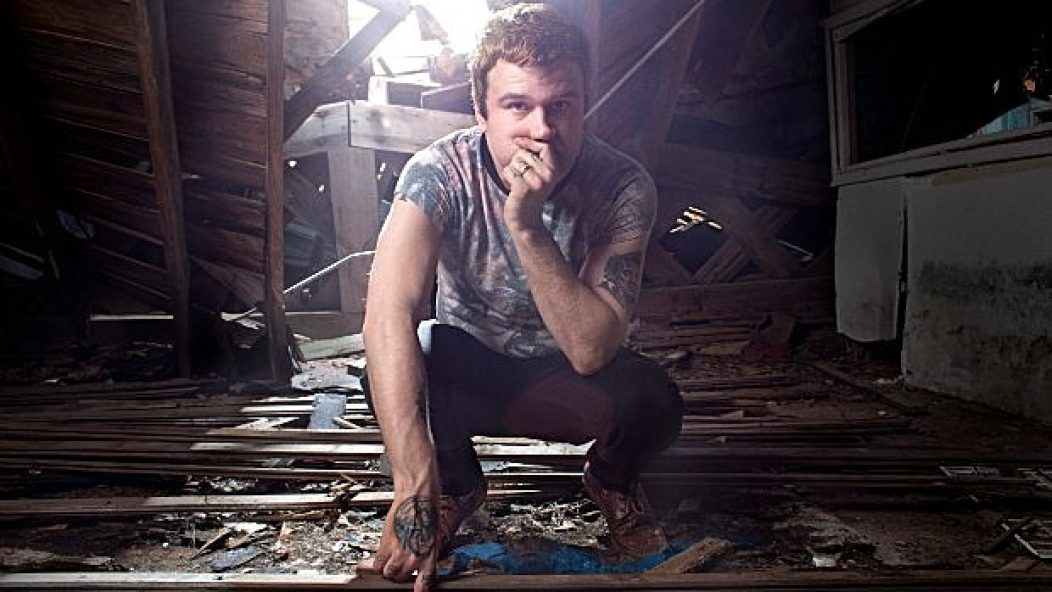

There’s this notion, especially in this music scene, that someone has to be “tortured” to be a good songwriter. What are your thoughts on that?

Someone like Elliott Smith was tortured, but not just because he was on heroin, but because he was a tortured soul. There’s an element of unrest I do think that does lend itself to being a good songwriter. Sometimes you deal with those demons and actually have a healthy, happy life, but you still have that inner conflict—which I do. I think people in general need to get over the cliché of, like, it isn’t about drugs or sex or egomania; it’s about whether you’re a questioning spirit or whether you’re that type of person who’s wondering about the world a little too much. I think as long as you have that quality, you’ll write interesting songs. But I do think it’s a sad cliché that people demand that celebrities and songwriters essentially have to be hurt and live unhappy lives. I think that’s a terrible thing. ALT