Op-ed: Re-evaluating the scene's culture of artist-fan interaction in the wake of tragedy

The senseless murder of YouTube star and The Voice alum Christina Grimmie shook artists and fans alike. After all, music in the modern day thrives on musician-to-fan interaction, either via social media platforms or meet-and-greets with signings and photo-ops.

One of the scene's biggest emblems, Warped Tour, is a hub of musician-to-fan meetings, hugs and expressions of love and appreciation. Festivalgoers have come to expect this. When that trust and expectation gets breached, though, how do we reshape these interactions—a crucial part of our culture?

Those moments aren't just precious for fans, however. Yes, artists get to meet the fans that support them, but these VIP experiences also rake in cash on the corporate end of the business; moreover, meeting fans can be a crucial growth tactic for smaller acts.

“Where artists were once viewed as out of reach from the public, today's fans expect to be in close proximity to acts and are willing to pay a premium for that access,” Ray Waddell writes for Billboard. That's nothing new to today's music fans. But while much of this desire for access is innocent, one tragic incident can rob artists of that trust, and well-meaning fans of that experience.

“We create enhanced experiences that make going to a concert or a festival more enjoyable,” Dan Berkowitz, founder of CID (a company that produces artist VIP experiences) says, “but none of that is possible if our guests and artists are not safe.”

Artists are often asked to constantly toe the line of safety—especially female artists.

Fellow YouTube singer/celebrity and a friend of Grimmie's, Tiffany Alvord, told the New York Times, “Everyone who follows me on social media knows when I’m traveling….They know what I’m doing, where I’m performing.”

Add the risk of constant transparency to the many intersections of lax gun restrictions, gender, race, LGBTQ+ status and being in front of thousands of people a night, and artists are often put at an enormous risk.

“The first thing my parents said is, one: ‘You’re staying home,’ and two: ‘Is following your dreams worth it if it means risking your life?’” Alvord said.

In a scene like ours, where most of the bands stick around at the merch booth, we're directly jeopardizing the safety of the people we admire in pursuit of expressing that admiration.

The fact is, though, that those moments at the merch booth are at the crux of our scene. They're what help us feel connected to the bands we love; it fosters the strength of our smaller microcosm of “outcasts.” But is it selfish to ask not only for their music and their time, but also potentially their safety?

“For all the thousands and thousands of fans that say I inspire them and help them, there is probably just a handful that have a twisted perspective,” Alvord told NYT. “But it only takes one of them to be a threat. It only takes one to pull the trigger.”

But I like to think we're different, somehow. The interwined, close-knit nature that spans across our scene's many fandoms gives us the instinct to support and understand. It gives us the instinct to protect. We have always shown more love than hate, and if we absolutely have to sacrifice our desires to respect the bands we love, we will do it.

Perhaps more importantly, though, we'll fight to never give up the culture we've cultivated—one that waits for hours in line after a show just to tell the artist they love that their music changed someone's life. We'll show that we've never been afraid before, and we're not about to start now.

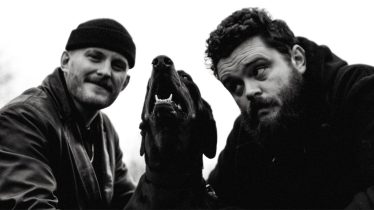

[Header photo by Jonathan Weiner. All Time Low, June 27, 2012, Vans Warped Tour.]