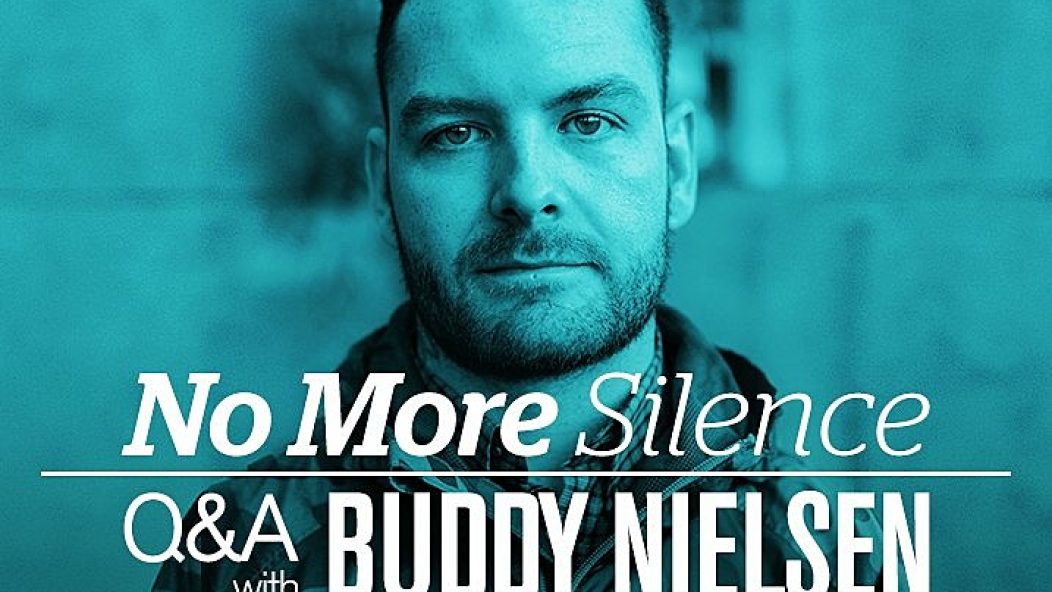

No More Silence: Q&A with Buddy Nielsen of Senses Fail

In recent years, SENSES FAIL frontman BUDDY NIELSEN has become one of the scene’s most prominent proponents of equality, an outspoken critic of a culture rampant with sexual aggression and bullying, and of musicians using their position to take advantage of fans. Nielsen has a long history of activism—his mom used to take him to Planned Parenthood marches in D.C. as a child—and in a lengthy conversation with AP, he tries to make sense of what solutions might exist to ameliorate these issues. It’s true there are no easy answers, because these problems are complex and pervasive, indicative of society-wide issues with patriarchal structures. “The music scene is a reflection of the larger culture,” Nielsen observes. In his eyes, it’s also not helping that the internet has irrevocably changed social interactions and communication—not necessarily for the better. “Why does it seem like everyone in our culture is doing fucked-up shit on the internet to women?” he says. “It’s a lack of empathy, a lack of understanding and a lack of ability to understand there’s consequences for the ways in which you approach and treat people.” Here, Nielsen speaks on what he specifically has done to create safe spaces and calls on all members of the music industry to be more mindful about how their actions affect other people, speak up about injustice and stop inappropriate behavior.

Interview: Annie Zaleski

Was there a tipping point for you to start talking about the sexual assault/aggression issues plaguing the scene?

BUDDY NIELSEN: I was doing this meetup that I did a couple times on Warped Tour. It with an organization called Punk Out. And it was all women, younger women and girls. The conversation was equally just as much about sexuality as it was about feeling unsafe. I had known that, but it was like, “Oh, this is really important.” When you give people a space, this is what younger girls want to talk about.

The real tipping point was when I came out. Anybody who knows anything about civil rights knows that [rights are] all inter-connected. The feminist movement is linked to the civil rights movement, [which] is intertwined with the queer movement. It’s all intertwined. They’re all one equality and they’re all in a timeline.

When I started to speak about it, I realized how angry people get— which means it’s truthful. When you say something about it, and you get this really visceral, aggressive reaction, that’s how you know you’re talking about something that matters, and is meaningful. There’s so much of a threat to this idea of… gender, in general. It’s even more difficult for people who have fluidity in their gender than it is for somebody [who] is able to identify, “I’m a woman” or “[I’m] a male.”

It’s a really interesting time right now, because you have this large group of people that literally feel that compassion and caring about people is going to be “the downfall of this country,” which I think is literally insane. When I became a Buddhist, I really cultivated caring about other people in a way that I wasn’t able to do before.

In late July, you went on Twitter railing about how all this is not the way it used to be, but unfortunately it is the way things are now. Is it getting worse or is that just a perception? What’s changed over time that has made it a particular problem now?

Years ago, there was a lot of physical communication. You meet someone at a show, you find them attractive, you talk and you develop some sort of relationship by communicating. Then you decide you want to hook up. Everybody in our country and all over the world has had experiences where they’ve done that. It’s been okay—it’s not been a disaster, and it’s not been bad. You end up hooking up, do it in a way that’s responsible, and you communicate what you’re doing.

The internet changes everything. Now if you do feel like something wrong happens, you have an outlet for it. Whereas before… You can’t really go to the police and be like, “I hooked up with this guy in a band, and he raped/sexually assaulted me.” You can’t do that. It’s the internet devolving the way in which we communicate. If I wanted to show a girl my penis, I had to do it in person. [Laughs.] You know what I mean? That changes the whole dynamic; [it’s not] like, “I’m just going to send this girl a picture of my dick. I’ve never seen her—I don’t know how old she is.” It changes the whole ethical play on both sides.

[Human beings] communicate very much by facial recognition and structure, hand movements and gestures and body language. When you just have the internet, all that disappears. You’re really not communicating. We’ve also lost a lot of our ability to tell what kind of conversations are fucking happening.

[Back then] I don’t know if it didn’t happen; I didn’t hear and see it as much. You knew there were guys in bands that were doing sketchy shit. That was a thing. But it was also not allowed as much. In the way that you see something and maybe say something about it? Like, “Dude, that’s kind of shitty; it’s kind of sketchy.” You’d have communication with other bands, and be like, “Yeah, man, that’s not cool” or “Did you ask that girl how old she is?” Simple questions like that. People used to do that—literally, people would be like, “How old are you?” There were situations that were avoided by communicating. They still happened, of course. It’s one of the reasons why it doesn’t seem as widespread back then is because there’s no way for a girl to report it, other than go to a magazine or go to a newspaper. That’s a big undertaking for somebody who’s been a victim.

I think it’s two-fold. On one hand, people reporting it are more likely to report it now. On the other, people are literally just doing whatever they fucking want, because there are no consequences and because of the internet. People are getting together in these sexual situations, because they’re not communicating. I don’t necessarily think guys have gotten worse or better. I think everybody’s kind of stayed the same. [Laughs.] It’s just the forum in which everybody’s coming together has changed, and it drastically changes and puts people at risk for walking into situations they don’t feel comfortable in.

It feels dumb to say, “How do we teach people how to communicate?” But it feels like there needs to be some teaching of, “Here’s how you navigate these situations. Here’s the best way to handle this.”

I think a lot more responsibility needs to be put on guys. It’s all on the bands. It’s like, just stop hooking up with your fans. Stop doing that. Stop making the situation about that dynamic. Stop using the internet to meet girls who like your band. It’s not a functional way to do that. I know this is going to bother some people, but if you are going to meet a girl at a show, meet them at a show. Have a conversation with the girl. Decide whether or not you like each other, rather than this really shitty way of communicating.

It’s also on their managers and the people around them—the people that are in charge. All these kids are young, and all they’ve known is the fucking internet. They’re stumbling around in this world, where there are no consequences and then out of nowhere, there are consequences and they’re like, “Wait a minute, what the hell? I thought I can just do whatever the fuck I want.” They’re not understanding there’s a responsibility that comes with people looking up to you. You need to conduct yourself in a way that is probably different than normal people, because you have some sway over the way people are, and people who might be inclined to do things they wouldn’t necessarily do, because they appreciate you on a level more than just you as a human being. They care about what you represent. It’s almost like a teacher. I know that sounds stupid to put on a musician, but it’s like you’re a teacher. You have to respect that, and be careful when you enter into sexual relationships with people who might look at you like that. Or you just shouldn’t.

When we were really young, we did that. And then we stopped, because we were like, “This is too dangerous.” It’s just bad. I didn’t want to be that band that was hooking up with their fans, because it’s a gross, flagrant thing. We figured out really quickly that was not something we wanted to do, not something we were going to be doing as a band. And we didn’t.

Some bands do, and some bands don’t. The funny thing is, you [used to get] to know the girls that hung out with X band. You became friends with them and friendly with them. It was different. I know that sounds weird, but it was… There were all these people in the music scene that were hanging out. Now you don’t even know people; you just see random people walking around backstage, because everything’s just done on the internet and everybody keeps it real quiet. If they’re going and meeting people to hook up, they’re keeping it on the internet and meeting wherever the fuck they’re meeting.

[In the past] you got to know those people, and you had relationships and, ultimately, I think had a level of respect for them [as] human beings. That totally goes out the window when you develop a relationship online. There’s not this human being connection, interaction. You don’t feel as responsible for that other person’s well-being.

That’s exactly it. You forget there’s a real person on the other end of the screen. It seems weird to say, “Oh, we need to give people empathy classes,” or we need to teach people what’s right and wrong. This is the stuff that used to be common knowledge. It seems like something got lost in translation. What do we do? How do we move forward?

Back in the day, a lot of [the music scene] policed itself: “Yo, did you hear this dude in a band whipped his dick out in front of this girl that we’re all friends with?” You’d be like, “Well, let’s beat him up.” [Laughs.] I know that sounds barbaric and stupid, because I don't agree with violence, but when there's the treat of self-policing, you then go, “Oh shit. Maybe I shouldn't disrespect this person, because I know she's friends with this person, because I know shes' friends with this crew of dudes that are fucking badass.” That doesn’t change the deeper problem of “I want to disrespect people,” but it does stop the behavior. You just don’t have that anymore. That’s just not the way of the music. In the hardcore scene, there’s still a tight-knit group of people that are policing themselves. But in the Warped Tour greater scene of post-hardcore, emo, that’s just not the case.

I think a lot of it has to do with bands giving a shit and talking about it, honestly. If bands give a shit and talk about it—and talk about it onstage, and make it a point to talk about it and make it important—then it changes the future of people in bands. Bands dictate fans, who then want to be in bands who continue to make music and continue on influencing younger people. I don’t know how to change what’s happening right now. It seems like everybody’s just so ignorant to what’s right. I don’t even know how to change that.

Where do you begin?

I know people are trying to say, “Well, the dude was 18…” I didn’t talk to 15-year-olds when I was 18; I was in a van touring when I was 18, and I didn’t do that. Bands, labels and managers need to reel these bands in. When they sign a new band, literally do what the NFL does with these rookies: “Here is the code of conduct: Here is what’s right, what’s wrong. Here’s what we expect from you.” It seems like that’s not coming from parents. I think it’s not coming from parents, because we’re at this terribly awkward phase of technology where the people that have been raised now, all their upbringing of that social interaction has all been based on the internet. The parents didn’t know they had to teach them the difference between social interaction and internet interaction.

What do you do with the problem right now? You tell people to continue to come forward. I wish there was a better way to go about [things]. It’s all done online, and that’s the thing that sucks. The response is done online; everything is done online. There’s no resolution and that’s the shitty thing. It pops up; the person gets kicked out of the band or whatever—and then that’s it. I wish there was more legally people could do. But it seems like our justice system is only interested in the really egregious stuff. The simple, smaller things—they’re just not interested in pursuing those as being flagrant. I really have no idea how to change anything, other than I think what I can do is raise awareness to talk about it, and to hopefully educate people that this is an issue, because it keeps happening. It’s not like it just happens once.

Because so many people are online, does that education happen online? Doe it happen offline? What form would be effective?

I think both. Making it a part of school is important. This is [such a] default answer. What about people’s parents? What about the parents of these girls? If my girl was getting dick pictures at the age of 15, I would be fucking losing it. I would be, “What can I do to make sure that this person knows there’s some ramification?” That’s one of the saddest things about this whole situation. The only person that really suffers is the victim. There’s no recourse for anyone. You make this accusation and you really have no way to prove it. Everybody just immediately goes, “Is it true?” Everybody finds some way to say, “Well, the person was 18, and she was 15, so that’s like high school.” There’s a total difference between a 20-year-old dating a 17-year-old with the consent of both families, and everybody knows each other, versus these situations that are happening online that don’t fucking have that.

Even if my daughter was 22, 23, and she was assaulted, I would be like, “What can I do to further this conversation into real world action?” A lot of people are like, “Why don’t these girls go to the police?” Because they’re 17! Why the fuck would you go to the police when you’re 17? I wouldn’t. It’s not fair to expect everybody, especially young adults, to immediately go to the police. And with what information?

It’s not just an easy answer of “What do we do?” It’s structural, all the way from the top down of “How do people deal with sexual assaults in this country?” People don’t deal with it. If you start to look into it, people don’t deal with it. Unless it’s a rape, where the person is beat up and got bruises—and even then, some of those don’t get dealt with. That’s what people are looking for. They’re looking for situations in which there’s violence beyond the accepted amount of physicality in sex, to make it a crime.

I think you have to change the whole culture. I know that’s an undertaking. You have to change the culture if you want to change these little things. We want to change the way in which people talk to each other online in a communication. We have to change the overall way in which women are represented and respected. The way you change the use of words—the way you change what’s socially acceptable—is by people deciding it’s not. And actively talking about it. And actively making it known that there are people that agree. Once you start to put that statement out there, people go, “Oh yeah, I agree.” And you can create small communities and groups, and hopefully it gets larger. It’s not something that one person can do.

There are no easy answers, and it’s not going to happen overnight. It’s frustratingly incremental. In the meantime, what can we do to make safer spaces for people to speak up about these issues? How can we make it safer to speak up about these things?

I don’t know if we can make the internet a safe place. I don’t believe it’s possible. People need to decide that there needs to be more in-person stuff done. There needs to be people starting grassroots groups, and people stepping up as leaders, and creating community safe spaces. There are no safe spaces for people of color, for women, for people who are queer. And that’s the fucking problem. If there was [that space], we would be able to have more of a voice to demand safer spaces in the larger world that’s run mostly by rich, white, straight men.

That’s what I’m trying to do. I’ve started a group in L.A.—we’ve only met once, but I got certified in a form of non-violent communication and I’m going to do some diversity training, and hopefully go to UCLA next year for mindful awareness certification. I’m trying to find what people are missing. People are missing social interaction, real connection and communication. I know that’s not what people want to hear. People want to hear, “We can fix things with technology. We can fix things with social media.” But I don’t think we can fix any of the brokenness and division [with] that.

We’re such social creatures, and we need that [in-person communication]. One of the ways we can do that is literally have bands—and people interested in this type of work—[bringing] this shit into our spaces, into our shows. Making it safe by talking about it onstage, and by making these issues part of what they’re promoting as a band. I don’t expect everyone to go out and do diversity training, and/or counsel training and have pow-wows, sit-downs and meditations at their shows.

But I want to do that for the people on the tour, because I think if you’re doing that for [those people], they’re going to be more likely to want to connect with their fans in that kind of way, and provide that sort of environment for their fans.

Even at a show, it’s difficult to connect with people in a larger way, but you can demand that bands not say “faggot” you can demand bands not say “gay”; you can demand that people don’t say “bitch” and “cunt.” You can demand bands are more responsible and respective of understanding the environment they’re making.

It comes down to fans, as well, deciding whether or not they are onboard. Are you going to support the bands that do that shit? Are you going to support the bands that don’t care? Or are you going to support the bands that do? I don’t know necessarily if people are interested in supporting the bands that care. It’s fans demanding that bands give a shit, and really reflecting that with their wallet: “We don’t support bands that do this.” It’s up to bands and up to people within the music community to decide whether or not they want it to be a community, or whether or not they’re in the band to make money, and they’re going to break up in five years.

A band like Anti-Flag, who’ve been around for years and years: You know if you go to an Anti-Flag show, there’s going to be consequences if you yell “faggot” from the crowd. It has to do with adults making decisions to care about other people, and deciding that the altruistic idea is more important than making money. Basically, I don’t know if there are lots of those people. I don’t think there are. [Laughs.] That’s why I just focus on what I can do. I try my best—I know I have a loud voice and I’m calling people out.

I’m interested in changing small groups of people, because I think it’s the only way in which it’s possible. I don’t think you change large groups of people at a time. You can only reach a small amount of people at a time, and you hope that it reverberates. alt

This Q&A is part of our No More Silence series about the ongoing problem of sexual harassment in our scene. For more information, including hotline numbers and resource websites, please look to our initial post:

No More Silence: Sexual harassment in the scene by Luke O'Neil

Or, read further with our other Q&A's:

Q&A with Ash Costello of New Years Day by Lee McKinstry

Q&A with promoter Eddy “Numbskull” Burgos by Lee McKinstry

Q&A with Warped Tour sober coach Mike Farr by Lee McKinstry