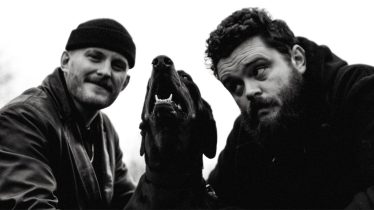

Sleep On It bassist talks medical troubles to instill fighting ethic in others

[Photo credit: Alex Smith/Anam Merchant]

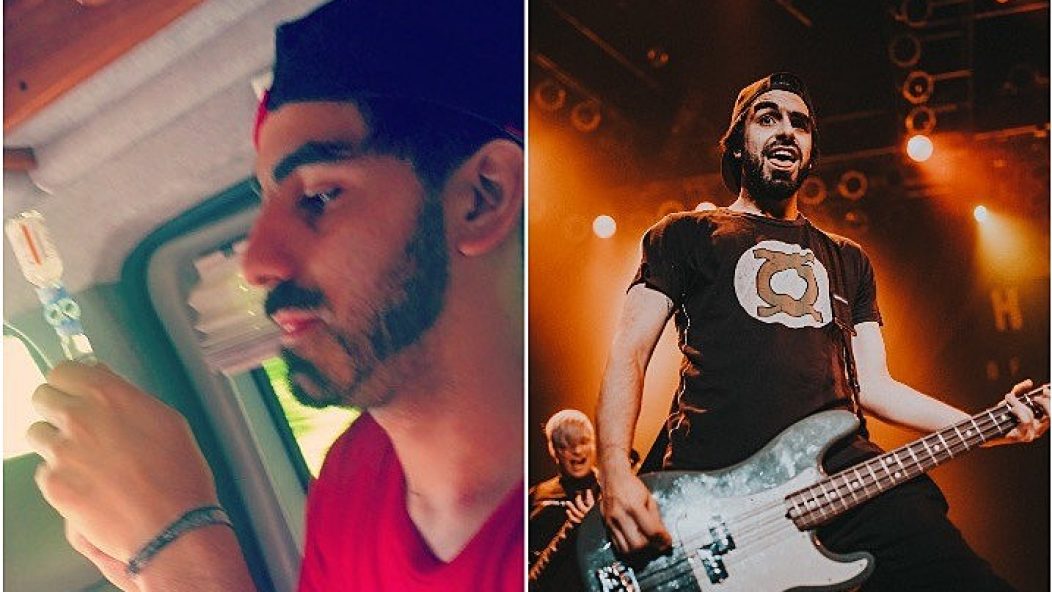

If you’ve ever seen Chicago-based pop-punk outfit Sleep On It play live, you’ll see bassist AJ Khah happily holding down the low end, bringing the hooks with his comrades.

But what makes Khah’s contribution even more spirited is that he’s living with Type 1 diabetes, a condition that hasn’t stopped him from pursuing his personal goals.

[Photo credit: Anam Merchant]

Diagnosed when he was 4, Khah didn’t have many friends growing up thanks to the eternal cruelty of schoolchildren. (They were afraid that they “we’re going to catch it.”) But he was given positive reinforcement from his years at Camp Kudzu, a diabetic youth summer camp in Georgia where he attended and would later become a counselor.

“My first memory is me being in the hospital and being told I’m diabetic,” Khah says, hanging out in his Chicago apartment. “I don’t remember much before that, honestly. I never saw myself as anything different; I just saw myself as a normal kid who just had to check my blood sugar every once in a while. My sister gave me this big speech about being diabetic. She told me not much was going to change, but that I was going to have to eat differently to react to what my body is telling me. She told me that I could do anything I set my mind to—I just had to go for it.”

Which is exactly what the bassist has done. Khah keeps a MiniMed portable insulin pump on himself at all times to maintain a normal level. (T1D patients have bodies whose cells reject insulin; essentially the pump assumes the function of a pancreas, supplying the hormone.) “Being diabetic in a touring band requires to not only think on your feet but be creative,” he says. “You always have to have this balancing act going on in the back of your head—especially right before you go onstage. You have to make sure you are right where you need to be. If your [insulin level] is too high, you feel like garbage. You feel like you’re walking through water and mud; your whole body is tired; you want to throw up, and your anxiety is making all that worse. If you’re too low, you feel like you can’t even walk. Everything is drained out of you. For me, I get pain in the back of my legs, which tells me I’m not able to do anything. It’s always something you have to handle.”

Khah jokingly refers to himself as “a whole bunch of problems,” citing other health concerns such as asthma, as well as allergies to peanuts and shellfish. (Anaphylactic shock is a drag no matter what kind of music you play.) He’s been able to navigate his needs with aplomb, citing the input of doctors, nurses, specialists and other diabetic patients who have lived with the condition. His sister told him about an app called One Medical that allows a patient to consult with a doctor via FaceTime and tells you where local pharmacies are located.

But even with technological advances, dealing with a long-term medical condition (especially when you’re not in a million-selling band) can be hellishly difficult. Khah chalks that up to the American healthcare system. “Being in a band is not what it used to be in the ’80s,” he begins. “[Touring] is not the most profitable thing, and the way healthcare in America is going right now, it’s super-expensive being diabetic.”

To accommodate for any financial shortfalls, he’s taken to playing a form of “medical roulette” in an effort to function. With a shopping list that includes fresh insulin, pump maintenance and the special test strips to get accurate blood sugar readings, sometimes Khah has to literally look within for guidance.

“One day, I had to pay $500 for two vials of insulin,” he reveals. “And I have health insurance, which is the messed-up part. But I’ve lived with diabetes so long, I kind of operate on what my body’s telling me. It’s a really dangerous game that I play. If I run out of test strips, sometimes I can’t afford to buy them. Insulin I spend the money on because I have to. But sometimes I need to make a decision: Do I eat, or do I buy test strips? There are times when I have to make that decision. And there it is: Sometimes I’m fine; sometimes I’m throwing up. I’m fortunate that I’ve had great doctors and great trainers. I used to be a camp counselor, and I learned from nurse practitioners who taught me a lot of things I try to use every day. But it’s kind of tough when you’re living in a van on the road.”

[Photo credit: Anam Merchant]

Of course, any pop-punk band worth their merch money have to maintain high levels of energy onstage. While he’s a young dude in a band, he’s acutely aware of what he needs to do to keep himself safe. He gave up drinking while still in college (“I was a tank then; I don’t need to do it now”) and maintains his insulin levels while seeking proper nutrition. Traveling for weeks in a cramped van has its own attendant worries, from being able to check his blood sugar and securing healthy food—as opposed to the last greasy, blackened hot dog you always see in gas station rotator grills.

“That is the hardest part about touring,” he reveals. “There’s so much crap around you. You don’t stop at good places to eat—you stop at gas stations. My diet has a lot of fruit salads, a lot of cereal. Canada has some nice healthy food: Pita Express is great. But it’s a constant battle of balance.”

Khah says that for the most part, he hasn’t had many disastrous moments where his body clock and stage time didn’t line up properly. He cites a moment of massive heat exhaustion during the band’s stint on last year’s Warped Tour that floored him briefly. But there was one point in the band’s career during a brief string of headlining dates the band had booked when vocalist Zech Pluister first joined that really shook him.

“We played this 30-minute set in New Jersey in a little cramped bar,” Khah remembers. “It was hot as hell and no air conditioning—the absolute worst. Two songs into our set, I could feel my blood sugar just dropping. Like I said earlier, I never want my diabetes to stop me from doing anything. Even in my head, I was thinking, ‘I can get through this. You’ve never passed out before; you’re not going to do it now.’ I kept telling myself that. Honestly though, I don’t know how much I messed up!

“TJ [Horansky guitarist/vocalist] knew there was something wrong,” he continues. “He walked up to me and said, ‘There’s something wrong. Are you OK? Can you get through this?’ And I kept telling him, ‘Yeah. Let’s keep going.’ At the end of the set, I literally put down my bass and sat down. Our merch guy Alex has been with us so long and saw the set. When I sat down, I saw Alex sprinting toward me with a Gatorade and TJ ran offstage to get food [for me]. I didn’t black out; I was just super-weak and tired.”

Regardless of the physical roulette game he plays with his body, the limited financial rewards of touring in a van and all of the hoop-jumping medical insurance companies give him, Khah is determined to live life on his terms and no one else’s. He isn’t going to slow down: While the gambling on his body gets tiresome and scary, he’s not going to spend his life watching television in his parents’ basement. While he continues to bring the rock with his boys in Sleep On It, his second order of business is to instill a fighting ethic in every fan who shares a similar kind of medical backstory.

“I want to be able to say to kids with diabetes, you can be a cool guy; you can be a genuine dude; you can have diabetes and you can still make an impact in the world,” he says stridently. “Nothing should stop you. You can have a brilliant mind on the inside and have something to contribute to the world. Who’s going to cure cancer? It could be in the mind of an autistic child or a brilliant savant. We don’t know. But we need to give everybody the opportunity to show the world what they can do.

“Find out what you think your weakness is and turn it into a strength,” he offers as both words of advice and personal mantra. “If you have a weakness, look at it as a strength. I looked at my diabetes as a negative, but it taught me organization; it taught me how to be on top of things; it taught me how to deal with big, impending decisions; it taught me time management. And don’t let anybody put limitations on you—and don’t ever put limitations on yourself.” alt