Web Cover Story: How One Overzealous All Time Low Fan Exposed The Dangers of Social Networking

STORY: Luke O’Neil

Comb through any of the thousands of interviews AP has done over the decades and you’ll find one common refrain: it’s all about the fans. Bands are proud of their down-to-earth approach to fans; their casual interactions with them after the show at the merch table or outside the club. In fact, the idea of no barriers between the band and the fan is one of the most basic tenets of hardcore and punk, an idea that has manifested itself at indie venues for years where bands have literally eschewed the stage, opting for a more level playing field.

In recent years, the prominence of social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook have further solidified this equalizing balance in the relationship between fan and artist. Back in the ancient times before the internet, there was no way to know what your favorite band was doing at that very moment at all hours of the day. Now it’s just a tweet away.

Protracted waiting periods for band/fan interactions and the general scarcity of information coming out of musicians’ camps engendered a certain respectful distance for the band, no matter how populist they were in their politics or behavior at shows. Sure, fans would still go crazy at the concert, and many of them would hang out afterwards hoping to meet their heroes, or even go so far as to sneak backstage. But in the internet age, that model of fanhood all seems very quaint now. In a time where you can literally track down the movements of your band crush as he crosses the country, lands in the airport, gets in a cab, stops off for a bite to eat and then heads home, the idea of fanhood–or fanaticism–has finally found its perfect storm.

Blame the bands, too. One surefire way to make sure no one is following you is not to broadcast your whereabouts. But social mores still dictate that just because one has this information, it does not imply a license to act on it. This is something that most people have always known. Social networking has diminished that respectful distance. Fans come to see the artists on the same level as their friends. Look, there’s ALL TIME LOW frontman Alex Gaskarth’s Twitter feed sandwiched between your sister’s and a friend’s. One can’t help but begin to equate the two on a continuum of potential social interactions.

Stuart Fischoff, a professor of psychology at California State University, Los Angeles, who has studied the psychology of fan obsession, says social media has eroded these boundaries and made it easier for fans that may have already had a propensity to express their obsession inappropriately to act on it. But, he concurs, it takes two to tango. “Celebrities are using the fans and the fans are using the celebrities,” he says. Artists see it as a means to further their sales, or to enhance concert attendance. Twitter, in particular, confuses matters. “With Twitter, it almost feels like a one-on-one relationship,” he says. “You can personalize it: ‘He or she is tweeting me.’ All these things feed into people who have a little trouble holding it together in the first place. All of this can fuel vanities and passions and people who want to get next to you will make greater efforts to do that. The people who fly across the country to be at someone’s house also represent the biggest potential threat.”

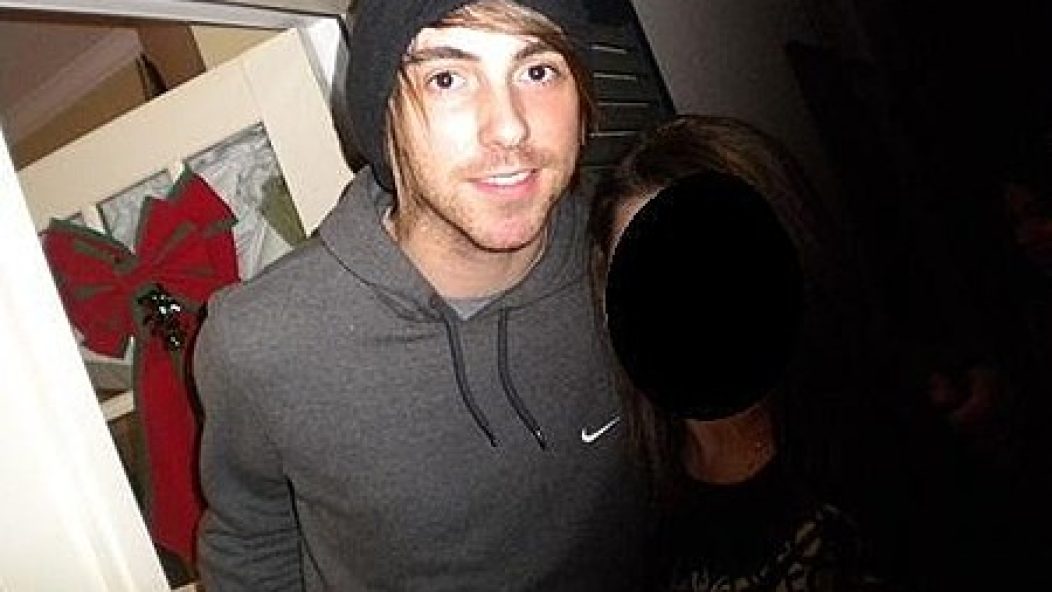

That’s something like what one All Time Low fan did last week, taking the idea of fanhood and crashing it right through the wall of stalkerdom when she tracked down singer Gaskarth’s home address, used Twitter to predict his arrival, then waited with her friends in the driveway until he got there. The most troubling part? She documented the entire story online with pictures. Tracking the development through other people’s Facebook and Tumblr sites is easy because the story has become such a flashpoint on the internet. “I got alex gaskarths address. seriously. i feel like a badass stalker. 😉 who wants to come sit outside his house with me?” reads the first posting. It only gets worse from there.

“YOU BITCH! YOU DID IT WITHOUT ME!” A friend responds. “Oh we are totalllly stalking him. MY IDEA! Hahaa :] we cann get arrested together.”

Maybe it’s all just harmless fan girl conjecture, right? It’s the type of thing kids say all the time when they’re talking amongst themselves about their favorite band. But when you consider the rest of the friend’s reply, and the fact that they actually went through with it, it starts to look much more troubling.

“OMG we could tell the cops he raped u[s] and then we could ride in the same police car as him! FUCK I AM GENIOUS.”

What follows is a sort of new-millennium internet-style descent into madness, and it would be pretty awesome if it weren’t so weird. Fortunately, this girl’s story has been met with widespread condemnation among her peers. Dozens of sites have reblogged it, and general reaction has been one of shock and disproval. Keaton Kustler, a 17 year-old from New York City is one of those bloggers who found it outrageous. “I think, yes, this is totally over the line, almost to the point of absurdity,” she says. “But at the same time, I am not entirely surprised by it. The pop-punk music scene has become pretty mainstream in the past year or two, blurring the line between fame and normalcy. Bands that I was seeing in completely empty, 50-person capacity rooms last fall are now all over MTV, going on world tours, and playing for huge crowds. I think that because of this phenomenon, if you want to call it that, fans feel like from initially meeting these musicians in more intimate situations they are able to build relationships with them, which is not necessarily the case. Fast forward six months down the road, the bands are selling out Hammerstein Ballroom, all the fans that have been following them for x amount of time believe that they have some sort of personal relationship with them, and ‘the guys’ are ‘just normal dudes’ and ‘the nicest people ever’ and ‘totally love me cause Jack remembered me!’”

That’s just the thing, they are normal dudes and ladies. They’re just dudes and ladies who happen to play a guitar or a sing well. They need to keep up as much of a normal lifestyle as possible in order to maintain some semblance of normalcy on the road. “When you cross the line from fanhood into the next level, it makes it difficult for the bands,” says Justin Aufdemkampe of Rise Records act MISS MAY I. “I think the line between being a fan and a stalker is realizing that people in touring bands or maybe your favorite band are people too. We still live normal lives and sometimes people take it too far and try and be a part of your personal life. I’ve had a few encounters with kids opening the van doors when you’re sleeping trying to get an autograph or girls saying they know you to other people when they have never seen you or talked to you before,” he says. “I do think sometimes musicians need to understand the life they do live will attract people like this so you should expect it sometimes, but it can get a little uneasy in some situations still.”

For example when you show up at a band’s home unannounced and hide in the dark waiting for him to come home?

“Sooo we found his address againn, and drove to his house. All his twitters and shit said that he was coming homee today but didn’t say whenn. Soooo we went to his housee, the lights were on but nobody would answer the door. Buttt, i got plentyy of pictures of Peyton and Sebastion. (their dogggsss.) Soo, like the stalkers we are, we waited outside his house for an hour withh nobody comingg homeee.”

Gaskarth, who didn’t respond for a comment on this story, took this incident in stride, even posing for pictures with the fans infringing on his personal space. Later, after the incident had time to sink in, he took to Twitter, (of course) to share his dismay. “Brb, building a castle wall and moat around my house. Archers will fire at anyone who doesn’t know the password” and “Creeped the fuck out by what went down tonight. Who waits outside of someone’s house for three hours with their lights off? Not ok.”

In psychological terms, this type of behavior is known as parasocial interaction. It’s a relationship in which one person knows a lot about the other party and the other does not. Rock bands and fans are a perfect example. There is a wide spectrum of how these interactions play out, says Fischoff. “You’ve got people who want to get close, perhaps do harm to somebody, depending on how complex the emotional reaction they had to the star or celebrity. You’ve got people that are delusional that they think they’re supposed to kill somebody like John Lennon, then you have people who simply want to marry them, or be their lovers.”

But why is that? Celebrities serve a lot of different functions for people. “Depending on how stable the personality is, those functions can become flattering and complementary,” he says “or obsessive and lead to stalking.” It all depends on the stability of the fan. “There’s an ability we have to recognize who we are, what constitutes us, and who are other people, and recognize that you have to give them a zone of their own separateness,” says Fischoff. “Some people can’t do that, they’re always leaning on people, putting their hands in other people’s food, touching people. These peoples have more boundary difficulties. That’s what we see physically, but psychologically it can be something where the person doesn’t recognize that the celebrity should have a life that’s separate from the fan’s adoration of that celebrity.”

The reason these types of interactions have taken on a different tenor in the internet age is because social media has tipped the balance of information toward a slightly more even level. A young music fan like Kustler says that bands encourage this sort of thing to an extent. “In terms of social media, things like this have already happened, but initiated by the band,” she says. “Do you remember when Britney Spears had [fans] ‘find Britney in NYC’ based on her Twitter riddles? What happened with Alex and this stalker fan is the same thing: [The fan] put together the riddles of where he lives and when he would be there. The barriers that social media have broken have helped artists develop better, more loyal fan bases, because of how it allows fans to interact and communicate with their favorite artists, but I think that these artists have forgotten about the potential repercussions. Do I necessarily think this is going to be a common occurrence? No, but if bands or anyone really doesn’t want every one of their Facebook friends and Twitter followers knowing their every waking move, they need to be more selective as to what the share with the world.”

Paul Banwatt of electronic indie duo WOODHANDS says they’ve had all manner of weird interaction with fans, ranging from the minor to the downright sketchy. One girl got hold of his partner Dan Werb’s e-mail address, Facebook page and phone number, and started texting him in the middle of the night. “Eventually it got the point when whenever we would go to the city she lives in, she would show up at the show and say these crazy things to Dan, the epitome of which was ‘My father told me I’m supposed to marry you and he’s been dead for two years.’“

But for every scary or annoying incident, there are plenty of positive interactions that arise out of social media too. After a show Banwatt thought was a bust, a fan sent him a Facebook message that cheered him up. “Before Facebook, I don’t even know how someone would send that message. I do think there’s a tough line, but it can be really nice too. There’s such an advantage to these type of things. It’s just so awesome. I wouldn’t trade it.”

“In some ways, it’s good,” says Krista Loewen of dance-punks YOU SAY PARTY! WE SAY DIE!. “I remember being a teenager and my friend and I e-mailed our favorite band, and when we actually got an e-mail back, it was so thrilling! Of course that was pre-Facebook or MySpace or anything. But getting personal interaction with a band can be super meaningful as a fan, and it means something to the band, too. [But] you’re open to a lot more negative attention. The internet is so instant and accessible, it’s not the same as the days where you would actually have to write a letter.”

That accessibility shifts some of the onus back onto bands to guard what they’re willing to share. “If you’re putting yourself out there as a person seeking public attention, it’s part of the new reality where you have to be a bit guarded in terms of helping people stalk you,” says Banwatt. He says he realized at one point that he had his phone number and personal information up on Facebook all while he was adding hundreds of “friends” he wasn’t sure if he legitimately knew. He promptly purged his account. Banwatt has also sent e-mails to bands he’s a fan of to say he likes what they’re doing. But, he says, “no one really thinks that what they’re doing is weird.” Until it gets really weird, as in the Gaskarth stalker scenario. One in which a fan, thinking she was going to have this meaningful, life-changing encounter with hero, really only ended up freaking him out. alt