Web Cover Story: It Takes A Nation Of Millions--Black punk and indie musicians on the scene's curren

P.O.S. at Warped Tour

STORY: Luke O’Neil

Here’s a little homework before we get this article rolling: Do a quick iTunes search for the band LET’S GET IT. Give them a listen. No peeking at pictures though. Totally solid emo pop, right? Now picture the band. You’re thinking maybe a pasty white dude with bangs in his face singing, right? Maybe a tatted-up kid in eyeliner? What about an African American?

Be honest, the third option is probably not the image that came to mind. But why is that? And does it really matter? Maybe the idea of race never even crossed your mind at all. Congratulations, you’re a part of post-racial America, but you’re not necessarily in the majority. Because–despite decades of evidence to the contrary–it still seems like people tend to think about varying genres of music as being racially segregated. White dudes play punk and indie. Black dudes play hip-hop and R&B. Sure there are crossovers, but they’re usually more the exception that proves the rule.

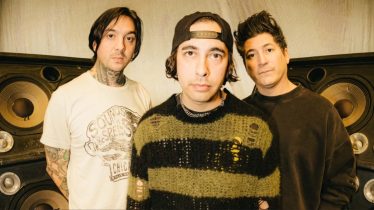

Let’s Get It

But just how big a problem are expectations of racially specific music and racism in general for African Americans in the punk and indie scene at this point in American history? “As a minority and frontman of a band in the scene, I see instances of racism all the time,” says Let’s Get It’s Joe Gilford. “Not all of the situations were hurtful or even meant to be so, however they are an indication of the current state of the race relations. I’m always mindful of the idea that there are people who might not be as open-minded as I am.” He points to incidents like Travis McCoy of Gym Class Heroes getting into a physical altercation on Warped Tour after being provoked with derogatory insults. “People do still pay attention to what color artists are,” Gilford continues. “Although certain artists are leading the way to bridging the gap, the idea of stereotypically ‘white’ and ‘black’ music still exists. However, this concept is meaning less and less every day. I attribute this graying of the lines to growing lack of importance to genre of music as people stop drawing lines and dividing music into small, dull categories and can start enjoying a wide pool of music without the politics of genre and racial demographics.”

Lawrence Caswell of Cleveland punk band THIS MOMENT IN BLACK HISTORY says that things are improving on this front. “It’s better than what it used to be,” he says. “I think younger kids think about [race] a lot less.” Part of that, he says, is the way that black popular culture has essentially become American popular culture. In 1993, when Dr. Dre’s The Chronic was released, there was a shift in album sales to include rap and hip-hop in the mainstream that went a long way toward loosening traditionally defined roles of race in entertainment. Before then, Caswell says, ‘It was like, okay, you guys do this and you guys do this.’”

This Moment In Black History

That was particularly true in the world of punk back in the late ’80s and early ’90s when Caswell was growing up. Although Cleveland has always had examples of African Americans playing in a variety of genres of music, discovering BAD BRAINS for him, like it was for thousands of other kids both black and white, was a transformative experience. “When I was younger, the bands that I saw that I liked who were playing the music that I was interested in, who were black and playing rock, you liked them because they were doing it. It wasn’t always because it was awesome. I really liked LIVING COLOUR‘s ‘Cult Of Personality,’ but that was about the level of stuff you were getting. Seeing Bad Brains, not just for black kids but also for everybody, it was like a click. ‘Oh, you can do whatever the fuck you want.’ I heard [1989’s] Quickness and it was like ‘Oh, shit. Yeah.’ It wasn’t like, ‘I can do that,’ but more like, ‘that’s much closer to how I feel.’ Not just because they were black, but because of the way they were approaching and thought about music. It opened up a realm of possibilities.”

The seminal Washington, D.C., punk band Bad Brains formed more than 30 years ago. Los Angeles ska-punks FISHBONE assembled in the late ‘70s as well, not to mention African American members of Suicidal Tendencies and Dead Kennedys, and the fact that Ice T’s punk/thrash Body Count song “Cop Killer” is almost 20 years old now. TV On The Radio, Bloc Party, the Noisettes, Black Kids, Santigold and many other artists are currently representing people of color on the indie rock side of the equation. So how is it possible that this is even still an issue? “I wish this topic wasn’t even worth discussing, but it is,” says A SKYLIT DRIVE singer Michael Jagmin who started a clothing line called Finding Equality to help racism awareness. “So many people are stuck under a rock thinking racism is a thing of the past. It’s still a large issue everywhere I go. Sometimes I wish I could find a rock that I could fit under, so I was oblivious as well.”

Caswell says to credit some of that to journalists, the ones who are most likely to ask about it. For many people, non-whites playing punk and indie rock still seems out of the ordinary. Stefon Alexander, the rapper known as P.O.S., has long played in punk bands and had crossover success within the scene–he even filled in on guitar for Underoath on this past summer’s Warped Tour when Tim McTague couldn’t be there. But P.O.S. says that it’s journalists who bring up the issue more than anyone else. “I’ve noticed people saying, mostly in interviews, ‘What’s it like to be a black guy in a punk band? Is it crazy?’ I think, to white people, if there’s a black guy in a punk band, there might be a certain novelty for a minute. I don’t think that’s news. I’ve been in punk bands all my life.”

Fishbone frontman Angelo Moore says it’s a question as old as the idea of punk rock itself. He’s been asked about race and punk rock so many times during the years, he’s become numb to it. Despite that, he still sees racism in the music business, and in the ways people perceive the blending of different cultures as a problem. “I haven’t really seen a big change as far as the stereotype that punk rock is usually white. That’s what you always hear,” he says. “But if you go searching deep, you’ll find every kind of culture and color of people play the same shit too.” Moore agrees that the media play a big role in the way this issue is filtered, but through negligence to expose the variety and depth of music being made. “You know the media, and the people who run the media, they are the ones who are responsible for what the majority of the world gets to see or think what’s popular, or what kind of person of color does this or what kind of person of color does that.” He says that some people don’t even know that the phenomenon of racism in music still exists. “They’re like, ‘Oh, nobody does that shit anymore.’ That’s almost like saying nobody ever drives down the street and calls people ‘nigger’ anymore. You wouldn’t think that shit still happens in America, but it still does. It’s a trip.”

Angelo Moore of Fishbone

It’s racism in music that served as the catalyst for things like Afro-Punk, a movement of African-American punk bands and fans based around a yearly festival and an online community that sprung from a 2003 film of the same name. Moore appeared in the film and says it should come as no surprise that black people are going to play punk music. “People are gonna play different music from different races of people. They’re gonna do that.“ But Afro-Punk came about because of that racist assumption. “[It’s] because of white society saying, ‘This rock music is ours, not theirs.’ Then black people had to say, ‘Hold on, man. We like to play it, too. By the way, we created rock ‘n’ roll anyway, so who the fuck are you to steal our music?’”

The Black Rock Coalition, a group founded in the ’80s by musicians like Vernon Reid of Living Colour, aims to break free from the genre-specific molds the music industry shuffles musicians into. “The Black Rock Coalition came into existence to let people know that there are black people who play rock and there are black punks, just like Asians and Latinos and everything else,” says Moore. “It’s an exposure thing.” Let’s Get It’s Gilford says that although things have gotten better, there’s still a way to go. “We’ve definitely made major strides over the years especially in the music industry,’ says Gilford. “However, just like in all of society, there are still struggles and battles to be won. A lot of the problems relating to race are ones that are a bit more ‘low key.’ Rather than focusing on etiquette and how a tolerant person should behave, we now have the problem of changing the way people think as far as stigmas and stereotypes are concerned.”

P.O.S.

Stereotypes and the assumption of cultural signifiers is one of the problems that P.O.S. points to from his time on the Warped Tour and touring with rock acts as being particularly problematic in musical race relations. “I definitely have seen racism in the punk and hardcore scenes. Actually, a lot of people don’t even realize that they’re racist or saying racist stuff. They assume that the overall vibe of that [music], like unity and stuff, is ingrained in the culture of punk rock. They don’t think about it. With the younger generations of hardcore kids–or whatever the [scene] is now where the kids have the keyboards–there’s so much, like, wearing a bandana forward or wearing your pants low or cocking your hat to the side; things that are co-opted from black culture, fashion-wise. Catchphrases get picked up and spread. Everyone has appropriated hip-hop slang, and everybody has taken pieces of hip-hop fashion, but when it gets down to Warped Tour kids, or any young kid who’s a fan of music, I don’t think they think where some of that stuff is coming from anymore.” Being on the Warped Tour and walking around the corner to find a bunch of white guys dressed like hip-hop dudes makes for an awkward experience, he says. Everyone gets quiet “because they don’t know if what they’re actually doing is okay in practice.” That’s a recurring theme with P.O.S. “Different members of different bands throughout my career have asked me my thoughts on the co-opting thing, whether it’s fashion, or adding hip-hop beats to breakdowns. It’s fine, but a lot of people take on the things they like about black culture and leave the rest behind. They don’t know where it comes from or why it’s there; they just know that it looks cool or sounds cool.” He says not all of that suggests that those who ask that type of question are outwardly racist because black culture has always been co-opted by the mainstream. “[Young people now] are as subconsciously racist as they always were, they just don’t acknowledge it.”

While it’s slowly becoming less of an issue on the surface, he and many others believe the root problems are still there. “I still see a look in people’s eyes, no matter how cool or comfortable they think they are with black people, if they don’t know me or barely know me and I walk into a situation,” says P.O.S. “People will mention racist jokes without realizing they’re racist jokes. A lot of people are oblivious. It’s the same as it was when they were growing up. They hear what they hear on the radio, but they don’t know any black people to put that into context.” It isn’t supposed to be that way, says Fishbone’s Moore. “Music is a catalyst to help break down racial barriers. Music is a catalyst that helps people free themselves from whatever troubles that bind them. With music, we sing against racism.”

But it doesn’t always work out like that. The arguably troubled origins of punk rock–one can make a convincing argument either way that the early days of punk were either the essence of racial harmony or the antithesis–plays into the ways these behaviors or assumptions have been filtered down through the generations. “I don’t think the roots of punk are racist; I think America is racist,” says This Moment In Black History’s Caswell. “Britain, too. In the early days we associate with punk in the U.K., that was a racist culture. There’s gonna be a racist element in that. But at the same time, there’s no punk rock without black culture and black people. It’s not just because of where the music came from, but also because of key artists who were very aware of black culture and incorporated that into punk, or were just black and changed everything like Bad Brains. All those early people loved black artists and talked about black artists, and they were a big influence on how punk came to be. Yeah, there was ton of racism in early punk, but it was just because it was a racist culture.”

Apparently it still is, otherwise we wouldn’t even need to ask this question–seeing black people behave outside of the parameters of their culturally coded stereotypes is still news. It’s the same thing within black culture as well, explains Moore, who says that black people are very conservative in their own expectations for what they should be playing as well. If it’s not hip-hop or R&B or jazz, “anything outside of that would be a minority when it comes to black culture.” Who could possibly care? Apparently a lot of people. “I don’t think not giving a shit means there’s no racism,” says Caswell. “I think now instead of it being, “Oh, there’s a black guy!” it’s more like, “Oh. There’s a black guy.” Adds Moore: “When people discover something like this, they say, ‘Wow, I didn’t know this was there.’ There’s a lot of ignorance going on. By ‘ignorant,’ that means they didn’t know. There are so many different colors on this earth, genres and cultures and races that play everything. One planet, one people. Idealistically that’s the way it should be. I don’t get caught up in the racist thing anymore because it’s there; it’s fucked up. I really hope it gets better. That’s my idealism, I guess you’d call it.” alt