Web Cover Story: Sex on fire--Did a band named "Sexual Assault" go too far?

STORY:Â Brett Callwood

The city of St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, became a hotbed of controversy last week after the band SEXUAL ASSAULT promoted a show by sticking posters around their hometown. The Feminist Action Collective swiftly condemned the poster, which depicts a woman with her legs spread and the band’s name plastered across her lower regions. The controversy brings back an age-old issue that has plagued rock music since Chuck Berry first sang about his “Ding-A-Ling” in the 1950s-can music devoted to being evocative go too far?

The members of Sexual Assault argued that they’re a punk band, and the job of a punk band is to upset, enrage and provoke. The history of punk is certainly littered with characters who have celebrated this, from Iggy Pop and his chest slashing to G.G. Allin’s penchant for throwing feces at his audience. But is there any room in today’s rock world for a band who use the abuse of women for their own means, whether they’re advocating such abuse or not?

Between 1987 and 1989, acclaimed Chicago punk producer STEVE ALBINIfronted a band called RAPEMAN and faced similar accusations. (Albini also produced Nirvana’s 1993 album, In Utero, featuring the song “Rape Me.”) Rapeman were named after a character in a manga comic from Japan that depicted gratuitous scenes of rape and torture against women. Albini became both bemused and obsessed by the book. “The name ‘Rapeman’ is startling but the actual character is actually quite baffling to western sensibilities,” says Albini. “[The band and I] were startled and shocked that this existed, and then we saw that there were dozens of these comics, and they’re an accepted part of Japanese mainstream comic literature. We were intrigued by the fact that you could eventually be dulled by the idea of a raping superhero; that it would become mundane. However, there was only a normal amount of sexual content in the material of the band Rapeman, and none of it had anything to do with sexual aggression or rape or that sort of exploitive or abusive dynamic. We were sometimes described in the press as being a pro-rape band or having rape-themed music, which was a matter of bold ignorance on their part. I don’t feel obliged to defend that position because it’s not my position. I don’t feel like I have to be the spokesman for rape.”

But what were Sexual Assault’s motives when they named their band? Guitarist Alex Andrews sheds some light. “We all decided on the name after one of our good friends was wrongly convicted of sexual assault,” he says. “It was just this ridiculous bunch of shit. Of course, we don’t advocate the abuse of women in any way whatsoever. [The band’s name is] open to interpretation, so if anyone interprets it that way, that’s on them.”

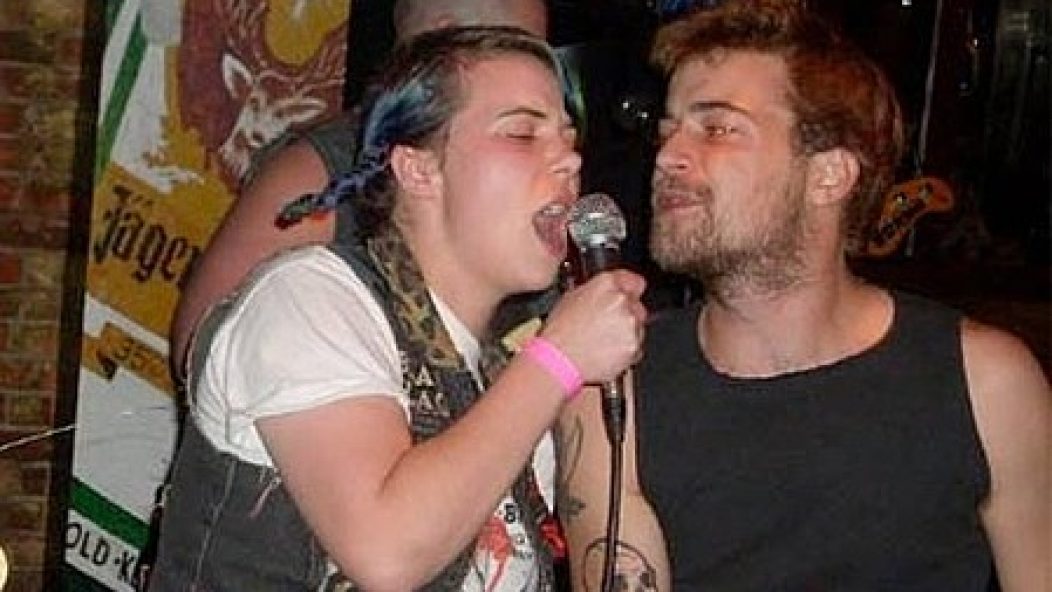

However, one could argue that if you’re going to call your band Sexual Assault and then print posters deliberately hammering home the theme, you really are nailing your colors to the mast. The members of Sexual Assault are clearly notadvocating sexual assault, but they’re playing with a theme that causes unease in many. Still, the singer of Sexual Assault, who happens to be a woman and goes by the name Mae Assault, feels that much is being made of nothing. “Sexual Assault are by no means anti-women,” she says. “Not only because I sing, write and silkscreen merchandise for the band, but because we have many fans who are women. All the members of the band are against the act of sexual assault against women as well as men. The punk community [in Saint Catharines] is [made up of] people who take care of each other regardless of sex, race or sexual preference.”

Still, Albini wonders if Sexual Assault could have shown some restraint. “The flier as described, which I haven’t seen, seems to be beating the drum a little hard on naming your band Sexual Assault and then having a woman in a suggestive pose,” he says. “It’s kind of crude, and I don’t know if I would have made that choice. You don’t name your band Sexual Assault without expecting people to take notice of it. To be honest, I would think it would be a bit of a naïve reaction to say that they were surprised that anyone was offended. It would be somewhat disingenuous to name your band Sexual Assault and notexpect people to notice that you have named your band Sexual Assault.” Andrews, however, claims that the level of outrage that they’ve caused doessurprise him and his band. “I guess we kind of are [surprised] because around here, we’ve put up so-called ‘offensive’ fliers for at least another dozen shows. We’ve been a band for around a year and this came just out of the blue.”

Tennessee death-metal band, COATHANGER ABORTION understandably receive a similar level of flack based on their moniker. “We get shit for our name all the time,” says drummer Scott McMasters. “It gets really old having to defend yourself, but that’s all part of being metal or punk. It’s gonna come with the territory. If you’re gonna stick your neck out there [with potentially offensive names or music], you better brace yourself–the hate is coming. Sometimes people are too literal and serious. Maybe they just have too much time on their hands. The people who have such a problem with these names and imagery are the same people slowing traffic to a crawl so they can get a glimpse of blood and guts in a vehicle accident. Hypocrites.”

The question remains, where is the line between freedom of speech and the public’s right not to be confronted with sexually aggressive marketing? Surely, as is usually the case with similar debates, common sense has to reign. If Sexual Assault hadn’t chosen to decorate their city streets with lewd fliers, then most people would have been none the wiser to their name, at least until they were touring. But that’s not what this band probably wanted. They were most likely aiming to cause controversy, because they believe that is what punk is all about. But Andrews is outraged by the media coverage given to his band so far. “These people have created a giant stink over this, and we’ve been portrayed in the local media as misogynists,” he says. “It’s so unfair and ridiculous. You guys are the only ones who have spoken to us. The local media hasn’t contacted us once–that would have been a better way of going about this rather than a big media crucifixion.”

However, there’s a cliché that applies in this situation: any press is good press. “Within three days, we doubled our views on MySpace through this,” says Andrews. “It’s great, as far as we’re concerned. We’re loving it.” But the moral issue of the band’s actions remains. Albini offers them some friendly advice. “Just be honest with people and talk to them. The more defensive you are, or the more you pretend to be startled by the response, the sillier you’re going to look. We actually had quite engaging conversations with a lot of the women–and it was almost uniformly women–who came to our shows with an interest other than seeing the show. As a man, I feel like women’s issues are not something I can really speak on with authority because I’m not a woman and so I’m not qualified. But I am in profound agreement with most of the direction of the women’s movement from the 1970s on.”

Mae Assault believes the line between between being evocative and offensive is wherever each individual person wants it to be. “Luckily, [everyone] is still allowed to have opinions of their own,” she says. “But I think people should examine a situation before they decide that a line has been crossed. If the feminist action groups that are so upset about our name and a show flier bothered to look into the situation before leaping on the smear campaign, maybe they would have realized we’re not anti-women or promoting sexual assault. If anything, we’re bringing [the issue] to people’s attention.” altÂ