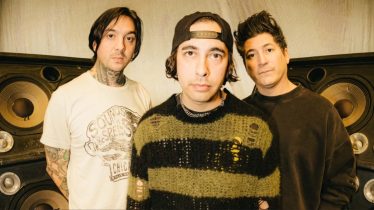

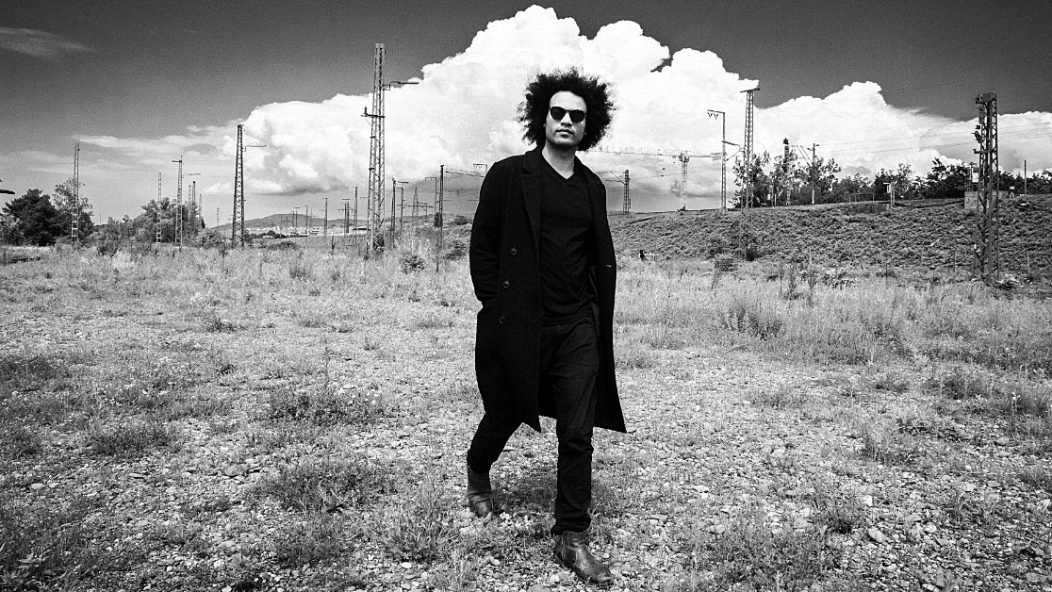

Zeal & Ardor: “We revel in the fact that we’re weirdos — it’s our job security”

This isn’t your garage band’s origin story. The musical moniker of Swiss-American Manuel Gagneux, Zeal & Ardor, was founded as an experiment. While living in New York, as an exercise to stay creative, he asked 4chan (the wholly anonymous forums, where anything goes — including conspiracy theorists and unchecked bigotry, a “cesspool,” as Gagneux offers over Zoom from his home in Basel, Switzerland) to submit two genres and he’d find a way to make them work together. “Someone said black metal and Black music, just not exactly that wording” — they typed the n-word — “and instead of getting my feelings hurt, I figured I could make a song and make it sound good. That would be a bigger F U than resigning. I ended up really liking how it sounded.”

A lot of people did. Gagneux’s first album, 2016’s Devil Is Fine, topped best-of album lists for its undeniable singularity — pulling from 1800s slave spirituals instead of more contemporary Black music like soul, funk, hip-hop or R&B. His second, 2018’s blast-beats-meets-blues Stranger Fruit, brought about a full band and more praise. Now on their self-titled third album, Zeal & Ardor are no longer a novelty act known for combining Alan Lomax-inspired field recordings and the cool industrial haze and satanic iconography of black metal — or for being the band that brands its fans like cattle (more on that, later).

Now, nearly a decade since those early 4chan days, Zeal & Ardor have to prove themselves. Luckily, Gagneux is up for the challenge.

Read more: 7-year-old metalhead rips through Slipknot’s “Sulfur” on ‘Ellen’

An interesting thing happens when you listen to a Zeal & Ardor record. For any music fan, it is an audial assault of the familiar, the abrasive and the familiarly abrasive. Early African-American spirituals sound like gospel, the soul that lays the foundation of much pop music, elevated by black metal, the sound of suburban rebellion. The two meet with different kinds of intensity, a philosophical blending as much as a sonic one.

“Both [genres] have this really compelling aspect to them. With the gang shouts and field hollers [in Black spirituals], that call-and-response thing, you intrinsically want to be a part of the music,” Gagneux explains. “Metal either flushes into your face, or it’s a huge gust into your back, which makes you feel powerful. Prefacing metal with gang shouts makes you want to become a part of it. It makes metal more palatable.” He often speaks like this: in poetic abstractions, interrupted by giggles, full of “playfulness,” he says, laughing. “Playfulness is what drives me.”

Jokes aside, only someone unafraid of experimentation could make this music work, or find a parallel between two seemingly disparate genres: a type of oppressive colonialism. Both Black spirituals and black metal “are a response to Christianity being imposed on them,” Gagneux says. “American slaves weren’t Christian when they came here. Thousands of years later, Christianity was imposed on Norway, and angsty kids made anti-Christian music. They rebelled against it, out of the privilege that they could.” Slaves, of course, were not allowed to dissent. They would risk extinction.

Read more: Nova Twins are making a difference in AltPress issue #402 cover story

The large caveat there — the major factor on which privilege hangs — is race. Gagneux is biracial, half-Black, with dual nationality in Switzerland and the United States. He pulls from Black music and what wouldn’t inaccurately be labeled “white” music (black metal is so often co-opted by white supremacists; NSBM bands like Burzum and Absurd come to mind), but he maintains that he wants to avoid becoming a “political talking head” for Black musicianship.

“I’m not qualified to give anything but my opinion. It’s dangerous to put too much value into musicians’ opinions because what we do is we make air decoration. And that doesn’t really make us wise in any topic.” It’s a remarkably self-aware realization, no doubt the kind a musician who grew up “in a family of scientists” might deduce. (It is that same environment that turned him off to Christianity. “They gave me a tour of religion,” he says of his parents. “I just couldn’t understand it.”)

Freedom, or more exactly put, fluidity, is his speed. Despite the black-metal portion of his musical makeup, Gagneux doesn’t consider Zeal & Ardor to be a metal band. (If they did, they might get booted off a few fringe pop festival lineups in Europe, and he’s invested in “the spirit of self-preservation… we’re going to open for Phoebe Bridgers,” and jokes that unlike some bands, who may claim to be impossible to define, “We’re liberal in what we steal from other people and genres. Look at it as candy: We have a lot of flavors… We revel in the fact that we’re weirdos. It’s basically our job security.”)

Read more: Rolo Tomassi’s Eva Korman on throwback playlists, Danny McBride and more

And despite the abrasiveness of his sound, he’s not angry. “I can’t yell at people [while] being myself. There’s an aspect of self-protection to [being a character on record and onstage],” he explains. “As a coward, I don’t want to give away my inner workings too much or too obviously. I think that takes a lot of courage, which I’m happy to announce I do not have.”

Even if Gagneux is playing a character — or, in simpler terms, avoiding diarism in song — like any great written role, there’s a purpose, a sense of agency behind the decision. And those, of course, are found on the records. Devil Is Fine, Zeal & Ardor’s first, writes revisionist history: What if American slaves adopted satanism? Stranger Fruit deepens those questions — right to its namesake, the Billie Holiday song “Strange Fruit” and the Abel Meeropol poem written in protest of lynching Black Americans.

Those inspirations come across in the composition, not the lyricism — there’s wonderful ambiguity to everything Zeal & Ardor do, which is why it might’ve come as a shock that his 2020 EP, Wake Of A Nation, addressed the Black Lives Matter movement, systemic police brutality and the murder of George Floyd head on. This third album returns to the form of the first two — an experiment in satanism, Black spirituals and black metal — with new pleasures. “It is still rooted under the alternative history idea. Devil Is Fine was living in indentured servitude. Stranger Fruit was about breaking out of that. This record is about being on the run. ‘We’re out. What do we build from this?’” Where would satanist slaves go if they were free? That’s up for the listener to decide.

Read more: Bad Omens on transcending rock with new album ‘THE DEATH OF PEACE OF MIND’

Elusive, but not unintentional. The unholy “Run,” an early cut on Zeal & Ardor’s self-titled third album, is a decimating listen — and a closer look reveals a man tormented by mental diaspora. “There’s always a little window open of, ‘I would profit from being this person in this situation, and people would take me more seriously or value me more highly,’” he says. “And there’s also always the option of not doing that. That song is about not conceding to the idea.”

Read more: Foo Fighters’ ‘Studio 666’ is ridiculous, stupid fun—review

“Götterdämmerung” is a not-so-subtle reference to the fourth part of German composer Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen, influenced by Ragnarök in Norse mythology, a war that brings the death of gods and the end of the world. It also flirts with this theme of no concession, just of a different kind — reclaiming Wagner because his work was famously appropriated by Nazis in World War ll. The song is “a conscious effort to claim his oeuvre to more leftist people. It’s kind of taking the piss out of Nazis,” Gagneux says. Add the fact that the song is performed in German, and it makes for an unsettling listen. “It’s such a harsh language that lends itself perfectly to harsher music. It sounds evil. As simple as that.”

It doesn’t take a lot of decoding to see the echoes of evil across this record. It’s in Zeal & Ardor’s German, in black metal and Gagneux’s co-option of Black spirituals — so often cast in American history as symbols of resilience despite the fact that these songs, meant to empower, were necessary tools to survival — slave songs created moral despite their very American condition; the hypocrisy is clear.

But it’s clearer in the satanic iconography that partners every Zeal & Ardor release. Take, for example, the cover of this self-titled LP: Two black hands act as mirror images of one another, recalling Baphomet, a goat-head deity often used synonymously with Satan, and his hands’ position. “‘It means ‘as above, so below.’ Baphomet has one hand up, one hand down — one for Solve, to dissolve, and the other one is Coagula, to coagulate. It’s basically the yin-yang symbol with eyeliner.”

Read more: ‘The Batman’ eyeing sequel ahead of potentially massive opening weekend

As an atheist, he laughs, but offers this to those who may find such iconography questionable: “Modern satanism is not really spiritual, but a philosophical inclination,” he explains. “It is about the fulfillment of your ego, yourself, as long as you don’t impede on other people doing the same.” He pauses. “There’s also some silly stuff like no mercy for the weak, which I can’t subscribe to — it gets into libertarian bullshit waters.”

Most importantly, without his own religion, Gagneux is allowed to pick and choose what works — another form of that fluidity, and freedom, the cornerstone of modern satanism — and how it appears in his work. “I will always romanticize that stuff,” he says. “The occult. The hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. That sounds cool as fuck! It’s very shallow in that regard — it’s like Pulp Fiction to me — but I can’t not like it. I like spec-fic, so I’m going to read it.” He jokes, but it’s clear: Experimentalism and a keen and clever open mind allows him these revelations. What if slaves were indoctrinated with satanism? Why hasn’t anyone asked these questions before?

Read more: ‘Beetlejuice 2’ might finally be happening at last

But what about the branding? For a short period of time — and for a cost of zero dollars and a world of hurt — fans could approach Zeal & Ardor on tour and get red-hot iron emblazoned on their skin forevermore. Disinfecting would happen afterward. If that’s not disturbing enough, try this on for size: The most recent time branding was in the news was in 2017, when it was revealed that Dominus Obsequious Sororium (DoS), a wing of the sex cult NXIVM lead by Keith Raniere, branded women he kept as slaves. A different indentured servitude than the kind who produced the music that so greatly informs Zeal & Ardor. So why do it? What’s the appeal?

“I’m really against the cult of personality, which is why I don’t appear in my videos. I’m saying this is an interview, which is hypocritical, but glossing over that,” Gagneux chuckles, “I wanted to make a statement that if you subscribe to something blindly, you might as well just get yourself branded. And branding? That’s what people did to slaves. So, we made a brand.” The symbolism, heavy-handed as it was made out to be, went over the heads of fans. “I didn’t think anyone would actually take us up on it. But eight people later, I figured let’s not do this anymore, because people don’t really get it. If you were to get it now, it’s you performing — not us.”

And for those who still might be intrigued — don’t be. “The smell is the most disturbing thing about it. I thought it would be, like, barbecue-adjacent smells. But it was hair. Burning hair, which everyone has everywhere. Now you know, reader. Now you know.” There never should’ve been a feeling of novelty behind the act, anyway.

Read more: Papa Roach announce ‘Ego Trip’ release date, share “Cut The Line”—listen

Instead, with the shock of being a cool new band and hot iron behind them, Zeal & Ardor are left with markedly a lot: Their songs. Their live set. A European tour with Meshuggah. A sense of optimism not heard on record, but the result in being able to — no pun intended — exorcise those demons. The ambition, now, is simple. “We’re going to stand on stages,” he says, laughing. “And yell at people.”

This story appeared in issue #403 with cover star Dominic Fike, available here.