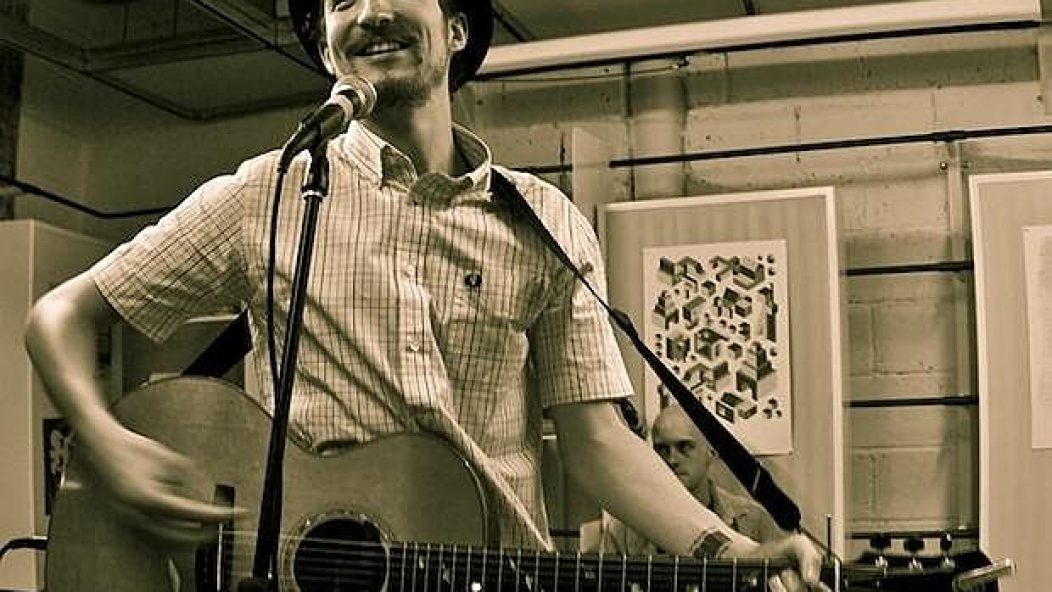

Interview: Frank Turner on the next album, selling out Wembley and sweating it out with Mongol Horde

2012 has been a very good year for English punk-folk singer Frank Turner. Still riding high on the success of his 2011 release, England Keep My Bones, Turner has played 116 shows to date, not counting his gig tonight in Baltimore or the four shows he played with his hardcore side project Mongol Horde (more on that later). Along the way, he performed at the Opening Ceremony of the Summer Olympics, sold out Wembley Arena and visited Conan to play his hit, “I Still Believe.” AP caught up with Turner during his stop in Phoenix to talk about his upcoming album, recording in California and the toils of performing in a hardcore band.

Interview: Brittany Moseley

Once the tour’s over, you’re heading to California to record the next album, right?

Yeah, we’re heading to Burbank, California. We’re recording with a guy called Rich Costey who is an amazing producer who I’ve dreamed of working with for many years, but have only recently had the time and the resources to work with. We did a week’s pre-production before the tour. He’s amazing; me and my band all love him.

The main problem that we’ve had—and it’s a good problem to have—is I’ve got way too many songs on the table. At one point there were 25. As much as it can be tempting to think of doing a double album, that’s generally not a good idea historically. The main thing right now is whittling down the song list, but even so it’s a good problem because it means that the finished record will be all killer no filler.

Have you noticed a theme developing among the songs you’ve written so far?

I try not to think too much about that kind of thing. To me, creation and analysis should be two [separate] parts of it. When I’m actually writing and recording and making the record, it’s important to me to just shut my eyes and let it happen and not get too analytical about it.

Having said all that, there’s obviously a few things I can tell you. It’s kind of turned into a breakup record for me, which means they’re maybe not the cheeriest songs I’ve written, but hopefully there’s some optimism in there somewhere.

What’s different about these new songs? What can fans expect?

I think I’m getting better at songwriting with time. I think these songs are better than the ones I’ve done before. I’m really happy and proud of how they sound, lyrically in particular. I really feel like I’ve been pushing myself lately to be more in-depth with what I do and what I say and with the poetry of the whole thing.

Musically it’s not unlike what I usually do. It’s a mixture of stuff that’s just me on my own with my acoustic guitar and stuff that’s done with the whole band. There’s some really quite heavy stuff on there and there’s some light acoustic stuff as well. Hopefully it’s a well-rounded piece of work.

Switching gears, I want to talk about Mongol Horde. Why did you decide to start a hardcore side project?

It’s something that I’ve wanted to do for a long time. I grew up with that kind of music and I played in heavy bands for a long time—much longer than I’ve played the music I play now. Also the drummer I’m playing with in Mongol Horde is a guy called Ben Dawson who I grew up with. He and I played in bands together from age 10 to 23. It’s never something we really discussed; we just knew we’d play together again. And then I finally found some gaps in my schedule to put things together and make time to write some songs, make some demos and do some shows, which was really good fun. It was kind of like scratching an itch, doing music that heavy again. It was quite creatively refreshing for me to do.

It’s definitely a side project for me, as in when we’ll be doing an album and a tour—which are both things I want to do—I’m just not really sure when we’re going to do those because it has to be on down time during my days off.

What was it like playing live with Mongol Horde at the Leeds and Reading festivals?

The shows were really hectic. We played for 28 minutes, I think our set was. [Laughs]. I discovered that I’m no longer 23 because at the end of the set I literally felt like I was having some sort of gigantic pulmonary collapse. It was really fun, and there’s something kind of primal-screamy about playing that kind of music and performing in that way. You come off stage and you’re utterly, completely 100 percent drained of all energy and emotion and sweat. It feels good.

Your background is in punk rock and hardcore. Were people surprised to see you playing that music again?

I think some people weren’t and some were. There’s still in the U.K. quite a few people who are into what I do and are into Million Dead, the old band I was in, and have seen me do that kind of thing before. I think there were some people who’ve gotten into me since I’ve been playing acoustic guitar who were a little taken aback by the whole thing. But in a way that’s something I wanted. For me, hardcore isn’t supposed to be comfortable. It’s supposed to be confrontational. It’s not supposed to be music that everyone likes and taps their toes to.

You’re on tour now, then you’re recording, then you’re going on tour in Europe, and then the new record comes out followed by, I’m assuming more touring. You’re like the hardest working guy in music.

Thank you I suppose. [Laughs.] I’m proud of my work rate on some level. At the same time I don’t want to get too excited about it because if you take the number of shows I do a year, it’s not dissimilar from the number of 9-5 office days in a year. My friends who work in offices don’t get awards and accolades for showing up for work every day. I have that added advantage that I do something I absolutely love for a living. I do cover a lot of ground and play as many shows as I can, but it seems to me, this is what I’m supposed to do. I’m supposed to be a professional musician.

It’s kind of like you’re a professional nomad.

For me it was a three-stage thing. When you first commit yourself to being a full-time itinerant, it’s very exciting and it’s all very Woody Guthrie. Then you have a little while when you realize the whole thing’s horrendous and awful and you haven’t got anywhere to go and you haven’t got any possessions. Then finally you reach the point I’m at now and have been for many years which is, this is just my normal day-to-day; this is my life. And it’s not especially hard or easy, it’s just normal for me.

In the U.K., you’re a pretty well-established musician, but in the U.S., you’re still kind of an underground act. Is it weird to have that dichotomy?

There are occasions when it gets a little schizophrenic, but—being the eternal optimist—in a way it’s cool for me because it keeps me on my toes creatively when it comes to being a live performer. It’s refreshing in a way. I think if I was at the same level everywhere in the world, it would be easier to get a bit more routine about everything.

Going back to the new record, you mentioned in your blog that you initially had some hesitations about recording in California.

I have to say—with no disrespect to the people of California—I took some persuading on that because I’ve always recorded in England, and my music is quite self-consciously English, and I want it to be that. There’s that lurking cliché of: English act does quite well, goes to California, gets porn star girlfriend and cocaine habit and disappears. I don’t want to make a record that sounds American, not because I have anything against America, but I think [England] is an integral part of what I do, in the same way that New Jersey is an integral part of Springsteen.

Having said all that, I really wanted to work with Rich Costey. I think that he’s a genius, and he doesn’t want to come to England so I guess we’re working in America.

One of the big things for you this year was your sold-out April show at Wembley Arena. Tell me a little about that.

It was great. It felt like the culmination of an awful lot of hard work. I said at one point toward the end of the show that it felt like every single person who was at that gig had seen me in a room that holds 100 people. I was hesitant about doing an arena show because I think intimacy is an important part of what I do as a performer, and it’s difficult—it’s not impossible—to present an arena show in an intimate way. I feel pretty confident that we pulled that off and it did feel like a connection was made with the crowd.