How Gracie Abrams became the brutally honest face of Gen Z pop

IT’S IMPOSSIBLE TO PINPOINT EXACTLY what it is about Gracie Abrams that is so damn captivating. Perhaps it’s the profound devastation that pours out when she whisper-sings about breaking someone’s heart. Maybe it’s her relatable online presence or the fact that her debut EP, minor, helped inspire Olivia Rodrigo to pen her 2021 viral anthem “drivers’ license.” It could be that she doesn’t have all the answers, and she doesn’t claim to — yet has mastered modernizing the art of bedroom pop in a way that embraces her forebears but is distinctly for e-girls. For all and none of those reasons, the world became fixated on the singer-songwriter.

The last two years were as equally eventful as they were uneventful for Abrams. She spent her time during the pandemic living at her parents’ home in Los Angeles, writing songs in her bedroom and going to therapy — she also became the Gen Z face of confessional pop, posting photos of her crying to Taylor Swift songs on Instagram (“tears for taylor”), awkward diary entries from 2010 and her adorable dachshund Weenie. She was just like the rest of us: an unabashed fangirl who also needed to hide beneath her comforter from the world sometimes. But she was also a prolific singer-songwriter whose songs cut through the deepest parts of herself, and everyone else, too. That relatability, that authenticity, became the bedrock of Abrams’ cult following.

Read more: Every Taylor Swift album ranked

Fame is complicated, but especially for a 23-year-old whose career skyrocketed during a pandemic. Abrams has learned not to get too caught up in it. She’s an “anxious thinker” and it’s taken her a minute — or roughly a year — to quell her anxiety around fame. Therapy has helped. So has focusing on what she can control. Mostly, it’s been grounding herself: keeping her head down and working and spending time with her close friends and family. Speaking over a no-screen Zoom call from Paris where she’s in the midst of Fashion Week events and press, Abrams is a self-described “sensitive person,” as thoughtful and open-hearted as the lyrics she writes, someone who eagerly gushes over her favorite things without hesitation, beams gratitude and still feels like she blends into the backdrop. “I don’t feel remotely as eager to be seen by anybody in any type of way,” she says firmly.

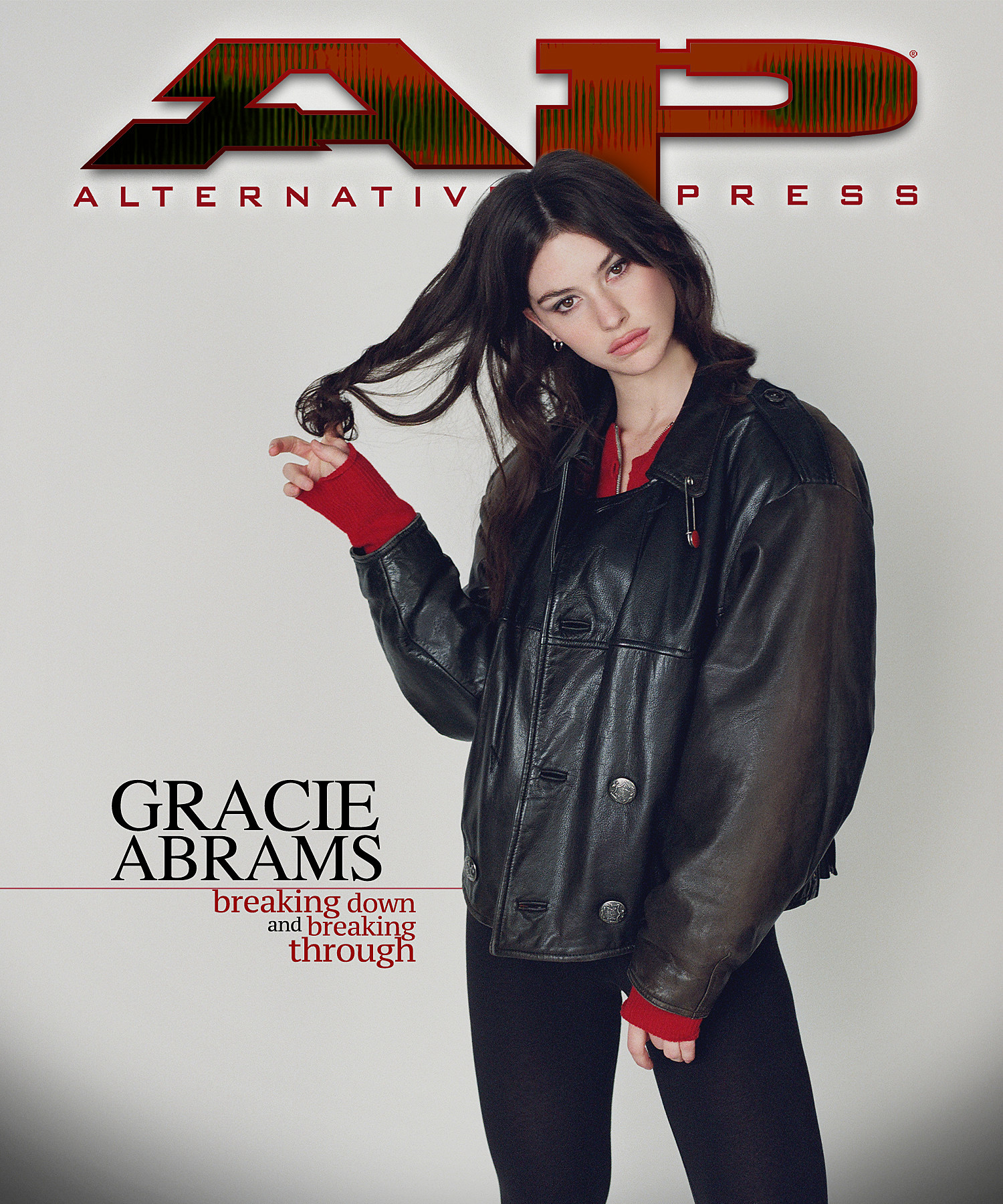

[Photo by Danielle Neu]

Truthfully, she doesn’t yet seem to quite understand the magnitude of her impact. “The fame feels, in the grand scheme of things, so minuscule,” she says, downplaying it. But it’s her mom’s advice that has helped her keep things in perspective: “Growing up, she was always like, ‘Just try to right-size the situation.’” Still, she doesn’t want to invalidate her anxiety. “It just helps put things in perspective a bit,” she reasons. Now, she’s in “the healthiest place” with her anxiety.

It helped that there the singer’s fame came in baby steps. In the midst of a pandemic, listeners were discovering Abrams through their screens rather than in the midst of crowded venues, and it bred an extremely intimate connection with them. When asked about her fandom, she admits she’s still surprised by it herself. “Oddly,” she pauses, “it doesn’t feel remotely as intense as maybe the way that you described it just now.” Perhaps, it’s because that virtual connection has since turned into an IRL one. “The experience of touring over this past year allowed me to have an imagination about my music that I’m so grateful for and has given me a different kind of energy, attitude and perspective toward it that excites me and makes me feel so curious all the time,” she explains. That gratitude is her baseline.

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Abrams grew up in a creative family (her parents are director J.J. Abrams and film and TV producer Katie McGrath). Like most kids, Abrams’ first foray into music was in grade school. But it wasn’t until high school that she found her penchant for penning songs. After graduation, she attended Barnard College, where she was studying international relations but left to focus on music. Soon, after igniting buzz around her songs on SoundCloud and Instagram, she landed a record deal with Interscope Records, and in 2019, she released her debut single “Mean It,” a taste of the emotionally wrought vocals, raw lyrics and sparse piano ballads to come. Her output increased during lockdown — she began playing Zoom shows, kept writing on her bedroom floor, and by 2020, she dropped her soul-baring debut EP, minor, which featured production from Benny Blanco and Joel Little (Taylor Swift, Lorde). The first single from the project, “I miss you, I’m sorry,” which now has over 131 million streams on Spotify, is the ethos of Abrams’ work — teeming with vulnerability, steeped in heartbreak and overflowing with self-examination: “You said, ‘forever,’ and I almost bought it/I miss fighting in your old apartment/ Breaking dishes when you’re disappointed/I still love you, I promise.”

By the time her sophomore EP, This Is What It Feels Like, arrived in November 2021, the world had been “sad-girl”-pilled by Phoebe Bridgers’ second album, 2020’s Punisher, Olivia Rodrigo’s 2021 debut album, SOUR, and Swift’s 2020 record, folklore. People sought comfort and community in art that evoked nostalgia and was a distraction from the emotional toll of isolation, the fall of democracy, police brutality and doom scrolling. So Abrams’ swelling folk-pop anthems (“Feels Like”) and wintry ballads (“Rockland”) became another balm for listeners who had been consumed by trauma, another respite from everyday horrors. By early 2022, she went on a headlining tour in support of the EP, and by April, she was opening for her longtime friend Rodrigo on the Sour tour. Things clearly weren’t slowing down, and behind the scenes, Abrams had also been working on what would become her debut album, Good Riddance (out Feb. 24).

[Photo by Danielle Neu]

THE WAY ABRAMS DESCRIBES LONG POND, the Hudson Valley, New York studio where she recorded Good Riddance, is like an enchanted forest hideaway in a picturesque snowglobe. She spent her days waking up at 10 a.m., writing, cooking dinners and having wine at the studio owned by Aaron Dessner — you know, the one where Swift recorded her epics folklore and evermore. “You can write about the most heartbreaking, twisted shit and then go on a walk with his kids, find lizards in the grass and then cook curry and rice, go to sleep and do it all over again,” she explains. It was all surreal for Abrams — and was the safe space she needed to be as vulnerable as possible without judgment. “I owe [Aaron] a lot for allowing me in, in that way,” she says lovingly.

Though she had never spent any time in upstate New York prior, there was a familiarity to it that was comforting. The fields, the trees, the creeks, it reminded her of Maine, where her mom’s family is from and where she grew up penning songs. Like Maine, Long Pond felt like somewhere she was most at peace — it was “sacred.” “There’s a magic that I have never felt anywhere else,” she remarks with a dreamy lilt, before adding that it’s “so deeply a reflection of who Aaron is as a person.”

Abrams was first introduced to Dessner by the lawyer they share just before COVID in 2019. “I had admired his work for over a decade and she thought that we might get along,” Abrams recalls. They ended up FaceTiming for an hour one day while Abrams’ anxiety was at “an all-time high.” “I hadn’t felt very comfortable talking to very many people,” she notes. But soon, he quickly put her at ease. After that, they didn’t talk for a while, but out of the blue in 2021, he invited her to Long Pond. She drove from Maine to meet him in person for the first time and ended up staying a week. “It became immediately obvious to both of us that [we didn’t want] to stop making music for a very long while,” she says.

That’s when the seeds of Good Riddance were planted, but it was a process. While it began two summers ago — technically — it wasn’t that linear. Over the course of two years, she visited Long Pond for five or 10 days at a time where she and Dessner worked in isolation. They dove in head first and picked up where they left off when she retreated upstate (“Obviously, he tinkered all the time while I was away.”) It took roughly 25 days to complete the 12-track LP.

[Photo by Danielle Neu]

For fans of Abrams, Good Riddance has the hallmarks of her earlier work, the vulnerability, the quest for clarity, but there is more palpable maturity and cohesion to the project. It’s something that likely comes with growing into young adulthood and also having a solid creative collaborator. It’s somewhat of an “aha” moment for her: “It’s definitely the most formative changes in my adult life that I was processing, thus far, in real-time as I was writing. I think a lot of the songs helped me release and let go of versions of myself that I stopped recognizing.”

Abrams was “desperate” to have more perspective in her relationship with others and herself — that meant taking more accountability in her songwriting. She spends the album’s 12 tracks mining a gamut of relationships — and, of course — heartbreak. “We’re circling the drain a little bit on a significant [relationship], but I definitely wrote about many different people, including my relationship with myself, my relationship with my family. There’s a whole variety of shit going on,” she laughs.

As she herself noted, Abrams does not spare herself — much of her songwriting on Good Riddance is self-critical. On opener “Best,” Abrams recalls in excruciating detail her regretful behavior at the end of a relationship with a deceiving warmth reminiscent of “Rockland” (“I destroyed every/Silver lining you had/In your head/All of your feelings /I played with them”); the whisper-soaked “Full Machine” reminisces about leading someone on, even though she knows it’s wrong (“I’m a roller coaster/You’re a dead end street/But won’t you stay for a while”); on the album’s lead single “Where Do We Go Now?” (which has a music video directed by “earth angel” Gia Coppola) Abrams drops the emotional facade of trying to make a relationship work and nods to her own preoccupation, with her work as one of the causes of its demise (“I know I changed overnight/So I can’t blame you for fighting/And I���d be losing my mind/If you lived in your writing”).

But Abrams also grapples with her own pain in the aftermath of her relationships. On the emo-tinged “I Should Hate You,” her voice cracks as she sings: “Pulled the knife out my back/It was right where you left it/But you aimed kinda perfect.” “I Know It Won’t Work” evokes the exhaustion and low timbre of Lorde’s vocals on “Ribs,” as Abrams is desperate to move on from a fractured on-and-off again relationship that her partner is holding out for. On the twangy ballad “This Is What the Drugs Are For,” Abrams ascribes meaning to color as she recalls the stark gutting devastation of losing the one she loves to someone else (“I’m still waiting by the phone/You painted my life indigo/A kind of blue I hate to know.”

So has writing in painstakingly honest detail helped Abrams get over her breakups? She’s not quite sure that’s real — not yet. “I don’t like the idea of devaluing what was real when it was real by being hateful or angry after the fact,” she says. She knows she’s been lucky and unlucky with partners in the past, but there’s, naturally, a deep gratitude there, particularly for one relationship she reflects on repeatedly throughout the album. “It was so formative and deeply important to me and will be for the rest of my life,” she says. Figuring out how to honor herself while not wanting the person she loved so deeply has been a work in progress. “It’s all impossible, I don’t know,” she resigns, metaphorically throwing her hands up in the air. “We’re all so fragile and soft, so I don’t know how anyone does anything.” She’s just trying to get to a place of acceptance when it comes to all her heartbreak.

Despite mastering the art of writing about the aforementioned subject, Good Riddance is much more nuanced. One of the standouts is the album’s second single “Amelie,” Abrams’ version of folklore’s “seven” — the narration of a dreamlike memory full of pining and innocence. It’s a song that’s special to Abrams. She can still feel the tangible stillness in the room when she debuted the track in Copenhagen on tour last year. It’s since become one of her favorites to play in general. “The feeling behind the song was really fragile, haunting, beautiful and eerie, and I wanted the recording to feel that way, too, so we kept it really raw,” she explains.

By the end of the record, “The Blue” sparks the promise of a new beginning with Abrams’ warbling with wonder over the shiny acoustic chorus. It is not a sad song. It’s why the singer enjoyed writing this one. “It’s hopeful and a little bit cautious, but at the same time, it’s very revealing of how ready I felt at that time to give everything to this person who I didn’t even know,” she explains. By stark closer “Right Now,” Abrams reflects on her growth, finally settling into herself, flaws and all.

[Photo by Danielle Neu]

WHETHER ABRAMS LIKES IT OR NOT, the release of Good Riddance is going to undoubtedly unlock another level of fame for her. It’s not just because she’s dropping her debut album; she’s also set to open for Swift on her Eras tour, which kicks off in March. A literal dream for Abrams, who has covered a handful of Swift’s songs including “All Too Well,” “New Year’s Day,” “my tears ricochet” and “this is me trying,” to name a few. It’s impossible for her to choose her favorites, though right now it’s a four-way tie between “The 1” (“The first time I heard that, I peed my pants.”), “Clean,” “Anti-Hero” and “All Too Well (10-Minute Version).” The night before this interview, Abrams hopped online and covered the Midnights cut “You’re On Your Own, Kid” at 4:30 a.m. “It was the briefest little snippet,” she laughs. “I sing her songs every day by myself, so you can just whip it out anytime.”

Aside from a comment on a TikTok, Abrams had never interacted with Swift until she texted her in 2021. “I got a text one random day being like, ‘Hey, Gracie, it’s Taylor. It’s my birthday, and if you’re in the city…’ Literally, she just invited me to her birthday and that was the first time we met,” she recalls, before nearly interrupting herself: “She is everything and more… that is the extent.”

Abrams has lived by the universal advice of Swift to all writers, which is “to operate from a place of honesty in your writing.” She’s not sure she would have approached songwriting “remotely the same way as a young woman” without her.

[Photo by Danielle Neu]

“The way that she would write about all versions of her experiences, not just romantic relationships, but friendships, homesickness and change in every possible way, allowed all of us who were partially raised on her songwriting to have an imagination in terms of how to be openly expressive with our own feelings,” Abrams says of Swift. “One of her greatest legacies is doing that for, I believe, generations to come. There’s a kind of vulnerability that I will permanently aspire to achieve that she’s laid out for us.”

When asked who Abrams wants to collaborate with in the future, Swift is, of course, on the list “permanently.” She’d also love to work with Lana Del Rey, James Blake and the National. But her number one dream collab right now? “I’m so obsessed with Ethel Cain.”

While Abrams herself is still grasping the magnitude of her fame and the effect of her vulnerable songwriting, nothing, including her dreams, seems too far out of reach.