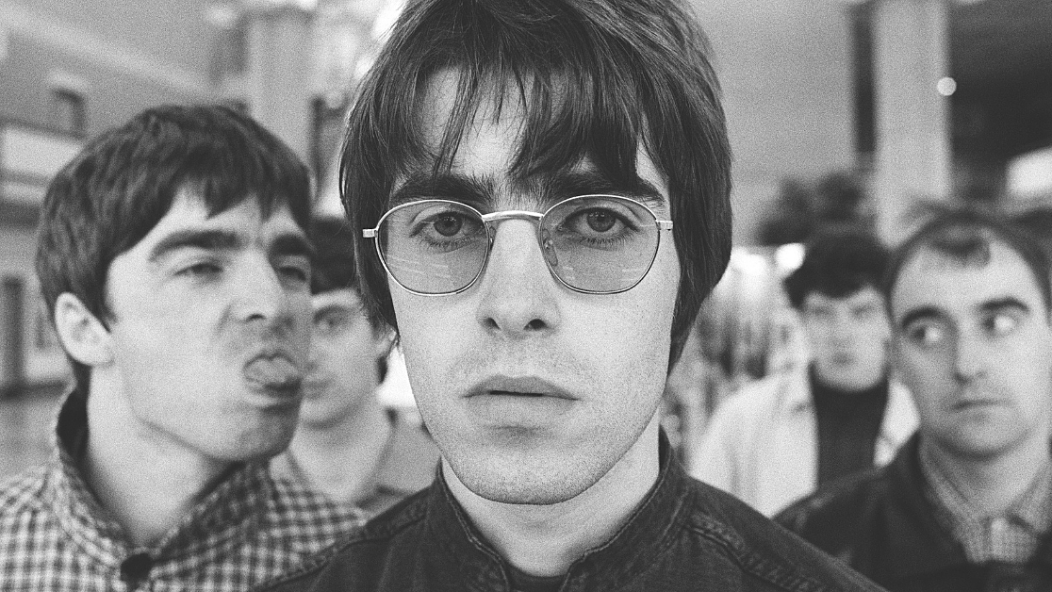

A history of Britpop, from Pulp to Oasis

“The Battle Of Britpop”

In its Aug. 26, 1995 issue, venerable U.K. pop weekly NME reported, “In a week where news leaked that Saddam Hussein was preparing nuclear weapons, everyday folks were still getting slaughtered in Bosnia and Mike Tyson was making his comeback, tabloids and broadsheets alike went Britpop crazy.” Homegrown pop groups Blur and Oasis, a mutual admiration society only a year before, had grown wary and antagonistic through 1995. Blur singer Damon Albarn said that Oasis “sounds a bit like Status Quo,” while Oasis mainspring Noel Gallagher snorted about Blur’s “Chas & Dave chimney sweep music.” It all came to a head when Blur dropped their new single, the foppish mock-music hall ditty “Country House,” the same day as Oasis unleashed their trad-rock stomper “Roll With It.”

The first serious English chart battle since the ‘60s heyday of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones was everywhere that week. No one was immune to “The Battle Of Britpop,” as the NME’s cover story declared it. It made for great, hyperventilating copy: Blur, the supposed upper-class musicians with a yen for intricate ‘60s-influenced pop songwriting vs. the mouthy, working-class Oasis who just wanted to rock.

The songs weren’t either band’s strongest; Gallagher shrugged in 2019 that Oasis’ “Cigarettes & Alcohol” and Blur’s “Girls & Boys” would have made a better musical wrestling card. In the end, “Country House” sold 274,000 copies to “Roll With It”’s 216,000, placing Blur and Oasis at No. 1 and 2 on the U.K. charts, respectively. As time marched on, Oasis became the bigger band internationally, and Noel and Albarn eventually collaborated.

Read more: 15 artists influenced by the Sex Pistols, from Joy Division to Oasis

What The Battle Of Britpop truly accomplished was bringing to the fore a new generation of English indie musicians tired of the dark, noisy American grunge that dominated the first five years of the ‘90s. They wanted something brighter and more poppy, reflective of British culture. Hence the term Britpop, devised by Sounds journalist John Robb to describe late ‘80s acts such as the La’s and the Stone Roses, though Madchester later became the accepted nomenclature.

Stuart Maconie, later a BBC Radio 6 DJ, applied it in 1993 to exactly the music it now typifies: Guitar-based, eyebrows-deep in U.K. culture, stitching together elements of the British Invasion, ‘70s glam and early punk bands whose songwriting was more sophisticated. Britpop came to be the musical wing of Cool Britannia, a new English pride celebrating fresh energy injected into art (Damien Hirst), fashion (Alexander McQueen), film (Four Weddings And A Funeral, Trainspotting) and politics (Tony Blair and the New Labour party). Its influence has endured far longer than Rod Stewart covering “Cigarettes And Alcohol.”

“Terry meets Julie, Waterloo station/Every Friday night”: Britpop roots

Maconie claims the term “Britpop” has been in usage since the British Invasion era — the last time England experienced a youth-driven cultural renaissance with worldwide repercussions. It could certainly describe the songwriting of the Kinks’ Ray Davies, especially when it progressed beyond the riff-driven protopunk of “You Really Got Me” to the Noël Coward-esque neo-music hall of “A Well Respected Man” or “Waterloo Sunset.” Davies’ songs became as obsessed with the details of daily British life as any late ‘50s/early ‘60s kitchen-sink drama. The Beatles seemed to follow his lead on such mid-period Lennon and McCartney compositions as “Eleanor Rigby.” Small Faces similarly displayed a yen for all things British in such original pub singalongs as “Lazy Sunday.”

This strain continued to fuel early ‘70s glam rockers such as David Bowie and Roxy Music, or early Britpunk’s more developed songwriters, such as the Clash’s Joe Strummer and Mick Jones, or the Jam’s Paul Weller. Tunes such as the former’s “Groovy Times” or the latter’s “The Eton Rifles” were as English as beans on toast. So, for that matter, were the jangly British tracks of the Smiths. Morrissey’s lyrics drew on a lace-curtain Britishness steeped in Oscar Wilde, Penguin Classics and late ‘50s Ealing Studios black-and-white dramas. And if there’s a more quintessentially English burst of jangly guitar pop than “There She Goes” by the La’s, it’s probably on a flexi disc glued to boxes of Weetabix.

Read more: 20 greatest punk-rock vocalists of all time

That said, there was no overarching Britpop sound, per se — just a number of bands with a common fondness for electric guitars, pop songwriting and documenting U.K. life. Pulp, for one, formed in 1978 in their native Sheffield, when frontman and longest-standing member Jarvis Cocker was 15. Founded as punk began folding into post-punk, they were reportedly so eclectic, a local fanzine thought they listened to BBC DJ John Peel nightly, seeking influences. They gained and lost members often, shedding and adopting musical styles just as frequently. So fragmented was Pulp’s musical personality, their 1992 album Separations consisted of one side of downbeat ballads and several acid house-inspired tracks on the other. Which is several kilometers south of the musical turf that eventually made Pulp major mid-’90s stars.

1988 seems to be the moment many of Britpop’s leading lights began moving toward their destiny. Blur formed in London that year, drawing upon the twin poles of Madchester and the pedal-happy shoegaze outfits. Fellow Londoners Lush began in the heart of shoegaze the previous year. Another set of Londoners, Suede, were centered around Brett Anderson and his girlfriend Justine Frischmann on guitar.

Read more: These are the 20 best English punk songs

Frischmann left in 1991, after she and Anderson broke up, leaving all guitar work to teenage whiz-kid Bernard Butler. She started her next band, Elastica, with brief Suede drummer Justin Welch. Her new boyfriend, Blur’s Albarn, temporarily played keyboards. Also in 1991, Liam Gallagher convinced Rain, a band he just joined on vocals, to change their name to Oasis. Before long, he brought in his brother Noel, a roadie for Madchester outfit Inspiral Carpets, since he played a bit of guitar and wrote some cracking tunes.

Not one of these aspiring indie outfits resembled what they became, much less the Britpop warriors all would become. But they’re all grasping toward their individual identities.

“I put my trousers on, have a cup of tea and I think about leaving the house”: Britpop begins

Blur had some modest U.K. success but weren’t exactly sounding like themselves yet. A slog of a 1992 U.S. tour, as Seattle’s grunge swamped rock scenes the world over, particularly the U.K.’s, got them thinking. “If punk was about getting rid of hippies, then I’m getting rid of grunge,” Albarn told NME’s John Harris the following year, as Blur unveiled their new Modern Life Is Rubbish album. “Damon and I felt like we were in the thick of it at that point,” Frischmann told Harris for his book The Last Party: Britpop, Blair and the Demise of English Rock. “It occurred to us that Nirvana were out there, and people were very interested in American music, and there should be some sort of manifesto for the return of Britishness.”

At roughly the same moment, Suede’s self-titled debut album, stocked to the gills with crashingly dramatic Bowie pastiches as “Animal Nitrate,” was the fastest-selling debut album in U.K. history. Frischmann’s Elastica, meanwhile, so successfully exhumed the ghosts of artsy late-’70s English melodic punk past — Buzzcocks, Wire — that their two-minute contrapuntal guitar bursts such as “Line Up” were brought to high court by the sources of their borrowed riffs. They nevertheless catapulted ahead of S*M*A*S*H and These Animal Men in the short-lived Britpunk revival that the music weeklies dubbed The New Wave Of New Wave.

Read more: The 10 best punk drummers of the ’90s, from Dave Grohl to Tobi Vail

In 1994, Blur’s Parklife dove even further into post-Kinks Anglophilia. Driven by infectious singles such as the herky-jerky “Girls & Boys,” it was their breakthrough album. It set the tone for other Britcentric releases such as Pulp’s His ‘N’ Hers or Oasis’ crunchingly glammy Definitely Maybe. The Oasis album beat out Suede as England’s fastest-selling debut, eventually certified seven-times platinum by the BPI for its 2.1 million sales. Blur then swept the 1995 Brit Awards, their nation’s version of the Grammys. They picked up four trophies, including British Album of the Year for Parklife, pushing ahead of Definitely Maybe.

This is perhaps the moment Liam and Noel Gallagher began sharpening their cutlasses. But before the Blur vs. Oasis chart war could erupt, Pulp unleashed Different Class, giving them their first No. 1 album and selling over 1.3 million copies in the U.K. If there was a moment when Britpop officially arrived, it was when Cocker led the entire 1995 Glastonbury Festival audience in a singalong of Different Class’ immaculate class anthem “Common People.”

“Baby, I’m ready to go”: Britpop’s Champagne Supernova

The Battle Of Britpop’s aftermath was a plum patch. You couldn’t wander into a Camden pub in those days without tripping over a fabulous young thing or 15 toasting their latest No. 1 with a river of champagne. Republica, Kenickie, Menswear, Supergrass — you name it, Britpop tossed out new names seemingly daily. Or even reinvigorated established careers, as in the case of Lush. Oasis’ (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? didn’t just sell 4 million copies in the U.K. alone, becoming the fifth best-selling album in the nation’s history. It broke internationally, on the back of Noel’s epic, widescreen ballads such as “Wonderwall.”

Oasis became the worldwide mammoth Blur couldn’t be, as the Gallagher brothers bickered their way across the planet, giving some of the most hilariously mouthy interviews in rock history. That mouth worked its way into acceptance speeches, too. As Oasis beat out both Pulp and Blur for several 1996 Brit Awards, Oasis sang a chorus of Blur’s “Parklife.” Which they renamed “shite life.”

Not that Blur were doing so badly themselves. The Great Escape sold over 1 million copies in the U.K. They just couldn’t seem to translate internationally the way Oasis or Elastica did. They had a plum U.S. season as “Country House” and “Roll With It” squared up back home, with “Connection” achieving saturated MTV and alternative radio play. It landed Elastica on the Lollapalooza tour, a number of U.S. TV appearances and brought them back to the States a total of four times over the course of 1995.

Read more: 10 reasons why Oasis are the most influential Britpop band of all time

Even as Britpop was looking so here to stay that newly elected British Prime Minister indulged in photo opportunities with Noel, cracks began forming in its fabulous facade. After the audacious victory lap of packing 125,000 fans onto Knebworth for two nights the previous year, Oasis’ third LP, 1997’s Be Here Now, drastically deflated all expectations. It started out selling well and got some positive initial reviews. But even Noel muttered it was bloated and overproduced. Then the Verve issued a masterful slice of existential pop called “Bitter Sweet Symphony.”

It made the longtime indie stalwarts worldwide stars, on the back of a clever video depicting singer Richard Ashcroft strolling down a street in a continuous single shot, shoving passersby out of his way, stopping only for a passing car. The victory was short-lived: A five-note string sample from the Andrew Oldham Orchestra version of the Rolling Stones’ “The Last Time” alerted sharkish former Stones manager Allen Klein. Owning the rights to Mick Jagger and Keith Richards’ ‘60s catalog, he sued the Verve because they’d secured rights to the sample from former Stones label Decca Records, not him. As a result, Jagger and Richards became co-writers. They received royalties until 2019, when the Stones duo signed their publishing for “Bitter Sweet Symphony” back over to Ashcroft.

Read more: These 20 songs will make you nostalgic for the 2000s

Perhaps the ultimate sign Britpop’s death knell was being rung, besides a large number of its star acts dissolving, was Blur finally getting its big U.S. hit… with a grunge song. “Song 2,” with its bombastic fuzzbox bursts and “Woo-hoo! When I feel heavy metal!” chorus, was likely a parody. But it came from their self-titled fifth album, which was saturated in non-ironic American indie-rock influences. Totally off-kilter, from the band that meant to “get rid of grunge.”

Blur persist to this day, off and on, when Albarn isn’t working on various projects such as Gorillaz. Oasis rolled along until 2009, when the Gallaghers’ chemistry became too toxic. Suede occasionally rouse to action, as well. Britpop became a degraded term over time. The style has seen numerous shabby revivals over time, most recently in what has been dubbed “landfill indie.” If Britpop’s spirit was more accurately tapped in the last 20-some-odd years, it’s in what the Libertines brought to the early millennium’s garage revival.

The example of a raw, shambolic guitar group writing well-crafted odes to a mythic Britishness, codified in their mythology as “Albion,” resulted in a million more homegrown neo-punk outfits. When it results in such delightfully English tunes as Kaiser Chiefs’ “I Predict A Riot” or the teenage Ian Dury-isms of Arctic Monkeys? Then Britpop’s true spirit will absolutely “Live Forever.”