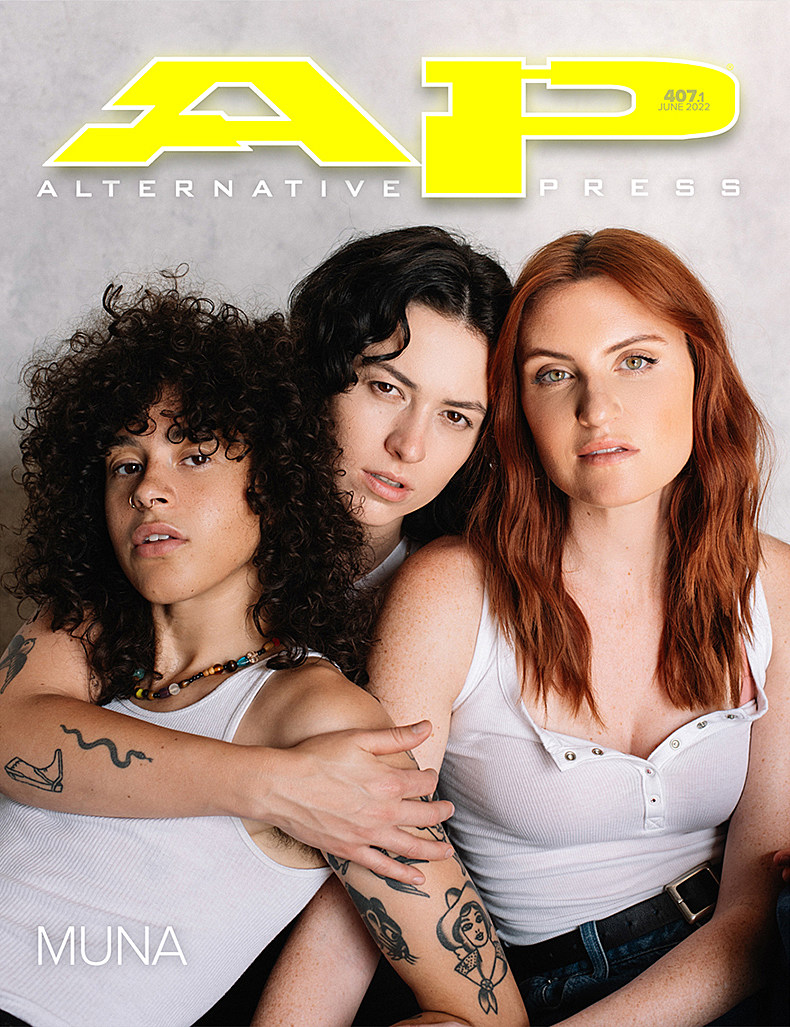

MUNA on making their self-titled album: “It’s impossible for us to not grow and change”

MUNA ARE ENTERING A NEW ERA OF RADICAL VULNERABILITY.

We know, we know — it hardly seems possible that the three-piece responsible for the track “Crying On The Bathroom Floor” could get even softer. But on their self-titled album, MUNA, they’re learning to open up in a whole new way, embracing love, fun and all of the mess that comes with it. “This whole era is about trying to have fun; that’s our vibe,” guitarist Naomi McPherson says. On the album’s second track, pop hit “What I Want,” they sing “I want the fireworks/I want the chemistry/I want that girl right over/There to wanna date me.” It’s something of a departure from the sad pop they’re known for, but that raw desire makes it even more tender.

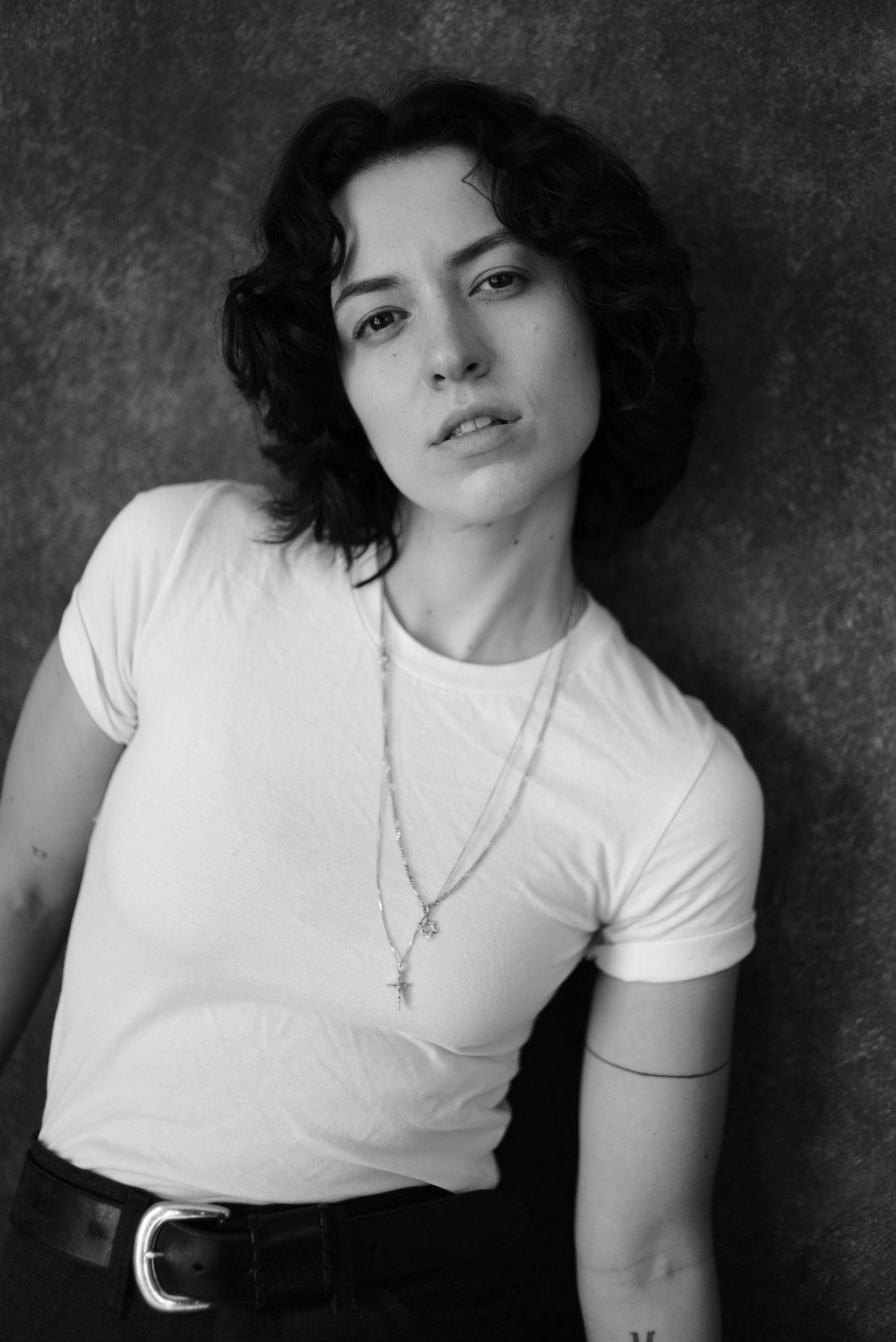

MUNA, formed of Katie Gavin, Josette Maskin and McPherson, met while they were at college at USC. Maskin and Gavin were in a freshman pop class (it’s fair to say they’ve passed with flying colors by now), while Gavin and McPherson met separately. “Katie introduced me to Naomi, and I found out Naomi played guitar and was cool. We just decided one day to jam, and the rest is history,” Maskin says. The three of them became friends and started a college band.

Read more: MUNA are entering a new era of radical vulnerability

The trio bonded in part over a realization that they are all queer — now, MUNA have amassed a huge fanbase of other LGBTQ+ people who see themselves reflected in their music and lives. Forming in 2014, the band decided to be out “from the jump.” “At the time, it was a different choice, and I’ll be honest, I spearheaded it a bit. I felt strongly about it,” Gavin says. “I felt like we were cool, and I wanted to be representative. I thought: We are queer, and we’re making great music!”

When Alternative Press catches up with MUNA, they’re all in separate spaces. Gavin has stayed in London after a stint of U.K. shows and The Great Escape Festival in Brighton, on England’s south coast, while Maskin and McPherson sit at home. Despite that, they seem to have a shared language, an almost supernatural level of connection that allows them to bounce off one another and seems to be part of why they work so well as a team.

After self-releasing an EP, More Perfect in 2014, the band signed to RCA, who released their EP Loudspeaker in 2016. Their first studio album, About U, followed the next year. Filled with glittering, dark pop and ’80s-inspired synths, About U was reminiscent of Robyn and Tegan And Sara. Its connection with their audience is part of what made MUNA so instantaneously beloved. Songs such as “I Know A Place,” an homage to queer sanctuary released after the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, made it clear that the band were at once political and unreservedly themselves.

Read more: How MUNA are embracing queer joy on their new self-titled album

After a brief hiatus, they followed About U with the more low-key Saves The World in 2019, a darker, less euphoric record that saw the band courting minimalism. With Saves The World, Maskin says, they felt a lot of pressure: “We really wanted to prove ourselves as serious musicians who could make a real work of art.” It worked, in part: Saves The World received five-star reviews nearly across the board, opening up new opportunities for the band.

[Photo by Lindsey Byrnes]

But they were dropped by RCA in 2020, leading to a rudderless period. That lack of direction, it seems, took the pressure off, giving space and breathing room to craft MUNA. “It’s more collaborative in a way, and also more lighthearted. With this record, we were just doing it and having a good time and throwing more things to the wall and not being as precious as we were when we made Saves The World. I think you can hear that in the music,” Maskin says.

The band continued to work on new music throughout the pandemic, and in May 2021, they found a new home in Saddest Factory, Phoebe Bridgers’ new label. “We knew Phoebe was starting a label, and we were like, ‘Oh fuck, that’s so cool,’ but we were at another label at the time,” Gavin says. “It was meant to be that our paths crossed further down the road. It just felt a little vibey, a little preordained, a little woo-woo, a little LA vibes. It felt like the right choice to make.” After announcing the deal, MUNA and Bridgers dropped “Silk Chiffon.” A pink-tinted pop anthem dedicated to sapphic love, “Silk Chiffon” marked a turning point for MUNA, a step down the road of queer joy.

“We had envisioned Phoebe being on that song even before we signed on the label,” McPherson says. MUNA had been toying with the idea of releasing songs with other queer people featuring on verses, and Bridgers immediately came to mind. “Once we signed to the label, we were like, we for sure have to get Phoebe on this song because it would be such a funny, fun moment for us and for her.” “Silk Chiffon,” which is so pure and tender and playful, made sense because it made so little sense, “it being such a happy love song from two artists, us and her, who make such intense, often devastating music,” McPherson says.

The track’s video was inspired by queer cult classic movie But I’m A Cheerleader (1999), in which Natasha Lyonne and Clea DuVall get sent to a conversion camp and fall in love. “We wanted to reference that movie because it featured queer joy when most queer movies were about devastating heartbreak. We feel like that is still something that deserves to be seen in pop music and queer art,” Maskin says.

“I feel like so many of the movies that we are provided end tragically, and it’s like, what are people walking away thinking about themselves as queer people? They’ll just think that we’re doomed to a life of misery, and that’s just simply not the case,” McPherson adds. “That movie was so ahead of its time in the fact that it was just a fun, delightful, camp movie for young people to enjoy. It was about conversion therapy, but it does not make you feel shame about being queer.”

[Photo by Lindsey Byrnes]

QUEER JOY, PARTICULARLY IN MUSIC, is less rare than it used to be. chloe moriondo, Snail Mail, Hayley Kiyoko, Lil Nas X, Years & Years… we have a wealth of artists who are out, proud and having a whole lot of fun with it. Still, MUNA want to pay tribute to the women who came before — the women who, for a while, were all we had.

“We’re standing on their shoulders. Tegan And Sara have been so supportive of us from the very beginning, which is so sweet,” Maskin says. Gavin adds: “It’s always been unbelievable to me because they’re legends. I don’t want to use cheesy words like trailblazers, but they are.” It’s the joy of Tegan And Sara, as people if not always in their music, that resonates with MUNA: “Something that I liked about them back in the day when I was a closeted queer and feeling so seen was that they are so fucking funny. Even though the music was sad, their personas and the way that they were at shows was so delightful,” McPherson says.

Read more: Watch MUNA perform “Kind Of Girl” on The Tonight Show

When MUNA formed, we were still living with that dearth of queer artists. While the band members were always out, About U was a little less specific. “On our first record, everything was gender neutral,” Gavin says. “It was always in the second person, which was a tactic I learned from Tegan And Sara.” There’s none of that shyness on MUNA: “I think we’re ready for it now. When I write a song and I’m writing lyrics, the people that I love are women and nonbinary people, and if that’s who I’m singing about, then that’s who I’m singing about. It wasn’t necessarily a conscious choice with this record.” That unashamed embrace of who they are is resonating further than they expected. “We can count cis gay men as part of the fanbase that listens to our music. If they can vibe, everybody can vibe,” Maskin adds.

[Photo by Lindsey Byrnes]

MUNA is even more of a pop album than their past two records, fully leaning into ’80s- and ’90s-inspired synths with romantic floor-fillers that are likely to make their fans dance and cry in equal measure. But there are also elements of experimentation with other genres here, like on “Kind Of Girl,” the record’s third single. A spiritual follow-on from Saves The World’s quasi-country track “Taken,” “Kind Of Girl” fully leans in.

Read more: 20 best stripped-down songs, from Spiritbox to Silverstein

“It was fun to mess around with. I like the narrative songwriting of country music, and I write often on acoustic guitar,” Gavin says. “There’s something fun happening now with a queer reclamation of the country sound and aesthetic. Lil Nas X has a lot to do with that, and also Kacey Musgraves, who is our straight queen!” she laughs, before adding that they were influenced by Musgraves’ “Golden Hour,” written with Daniel Tashian and Ian Fitchuk, who MUNA hit up for “Silk Chiffon.”

While country appears to be a typically masculine, heteronormative, even misogynistic space, Gavin points out that that isn’t always true. She references Indigo Girls, an iconic folk-rock lesbian duo. “There are these spaces you would think are historically straight and male, but they’re not if you look closer into it. Queer Black women are at the forefront of the development of any musical genre. ‘Kind Of Girl’ was a song that happened naturally, and we knew it needed a space on this album, but because we also in the band have different gender identities and gender expressions, there was always something funny about how gendered the song is,” she adds.

For the video, the trio played with the masculinity of country to the fullest extent, donning their finest drag king outfits. “We wanted to fuck with it a bit more, and we’re really proud to have a drag king video. There’s something humorous about it, but we’re not making a complete joke about ourselves. I actually felt really hot on that day. It’s mind-boggling and really cool to know that you’re one of few representations of that experience,” Gavin says. McPherson adds, “It’s a song about allowing yourself to feel fluid in who you are as a person. Even though it’s a very gendered song, to me as someone who is nonbinary, that is so deeply relatable. It’s about allowing yourself and your story to be fluid and to know that you can change. Allowing yourself room for growth in your life is such a nice place to be able to get to, where everything is not so prescriptive.”

[Photo by Lindsey Byrnes]

THAT GROWTH, BOTH IN THEIR OWN IDENTITIES and with one another, is a key theme for the band right now. Currently in their late 20s, the trio have been intimately close since they formed in their early 20s. Now, with MUNA, they’re starting to reflect on the impact growing up together has had on their lives. “They are my family,” Maskin says. “They are a reflection of who I am. I think we do that for each other, but we’ve just grown up together. It’s impossible for us to not grow and change.”

Part of growing together has been learning to resolve conflict, making room for their very different personalities: “Because we are so close and we have been doing this for so long, I think we are very good communicators and collaborators because we are friends and because we work on being honest with one another. It’s gotten better, and we’re shockingly closer than ever.”

McPherson agrees, and the three of them sink into a vulnerable self-reflection, going back and forth about everything they’ve learned together over the years. “I’ll totally agree with what Jo said. We are so incredibly lucky to have such deep and meaningful friendships with each other. It makes me feel so incredibly grateful,” McPherson says. “Our identities have evolved and shifted over time, but the essence of who we are as people and how we see each other has been the same from when we first started being friends. We’re kindreds in a way. Sometimes we have shit that we have to work through to better our relationships, but there is such a deep love and respect that we all have for one another, and a level of mutual understanding. I’m just so blessed and lucky to have that experience.”

Read more: How PinkPantheress uses 2000s nostalgia to craft a sound both familiar and fresh

Gavin, who’s been quiet and giving their friends room to speak, is reflective of the time they’ve spent together and the way it’s made them change. “We’ve gotten to make three albums together, and we’ve gotten to work together through the whole span of our 20s. I’ll speak personally and say that staying in this band and treating Naomi and Josette how they deserve to be treated is the biggest motivating factor in making personal changes that I needed to make in my life so that I could just show up in the way that I needed to,” she says.

[Photo by Lindsey Byrnes]

[Photo by Lindsey Byrnes]

“There are certain things that haven’t changed about me that I’ve accepted and I’ve accepted responsibility for. I’ve always been a really sensitive person. I still am; I have a lot of feelings. It’s a daily thing, and I get it wrong a lot of the time, but I’m trying to be aware of my feelings and take care of them and at the very least communicate with them in a loving way if I’m not able to be on top of it.”

Gavin says that McPherson’s girlfriend once said something that influences how she sees herself: “‘You’re such an intense person, but you know how intense you are, and you’re aware of it, and you can laugh about it,’” she laughs. For Gavin, that throwaway comment made a lifelong impression: “That’s such a compliment, and that’s a big win because it’s the best I can ask for. I cannot change things about who I am, but I can have a loving attitude towards myself about it and do the things that help me be in these lasting relationships with other people knowing that I am the way that I am.”

That vulnerability and ability to reflect so candidly on who they and the people around them are is what make MUNA so special to so many people. They have a unique insight, and while they’re likely too humble to admit it, that degree of candor is both rare and much harder than being cynical. For McPherson, it took a while to get used to being so raw. “It takes a lot to have trust in people,” they say. “I struggle with having trust that anyone can understand my experience. I tend to feel quite alone. It’s been a huge part of my growing process to have such close, intimate friendships that require you to be open and vulnerable when I would say I am inherently averse to doing that.

“It’s such a fulfilling process because sometimes you will open up about your needs and be disappointed if people can’t meet them, and that’s part of life as well, but when people are able to meet the needs you have and hold space for your emotions and the type of person you are, that’s just the most life-affirming, humanity-affirming experience you have, and I have that a lot in this band. I feel super lucky.”

Read more: How Soccer Mommy’s new album Sometimes, Forever made her go bigger and bolder

For the band, that difficulty being vulnerable at first manifested in an aversion to letting other people into their creative process. They insisted on self-producing their first record, a decision that made their job more difficult than it needed to be. “We were emboldened in our stubbornness. It made us able to do things that someone alone wouldn’t have been able to pull off,” Maskin says. “We come on really strong. I think we were insistent on self-producing the first record, when realistically, knowing what I know now, we were too green to have been given that much artistic freedom!” But Maskin doesn’t regret the decision: “Because we were given that freedom, which is such a rare experience for people who are not white dudes, it made us the band we are today. We were given opportunities that I know are hard to get.”

ON MUNA, KNOWING WHAT THEY DO NOW, they decided to go back to self-producing, taking control of the sound and feeling of the album. “It feels good to get back to self-producing and making music the way we used to make it. It feels full circle,” Maskin says. “It took a long time for us to want to work with other people when we started this project. I think also as people who are queer and of marginalized genders, there have been times where we have felt that we’re not taken seriously as musicians, so as a result, we have been insular for so long. I feel like with each other, that’s where we feel safest, to be vulnerable with making music generally.”

McPherson agrees, adding that they often felt unsafe in the music industry. “If you are of a marginalized identity, gender or otherwise, I think it literally can be unsafe to pursue music professionally,” they say. “Often times you are put in rooms with people who are older than you, who are creepy dudes, and I’ve heard plenty of horror stories from plenty of people about what it can be like in those rooms if you’re by yourself as a young person.

“I think we were aware of the fact that we were othered and that opening up could be dangerous, so we felt safe with each other and kept it at that for a while. It took a while for us to not be hyper-vigilant about our own safety,” they add. The band came to realize that, at a point, they needed to learn to be open with other producers and musicians: “I think your paranoia can be a bit outsized, and it is helpful to work with other people. Sometimes you have an aversion to doing that if your experience is an othered experience.” Still, at this point in their career, they do have the creative freedom to choose the artists and collaborators who they feel comfortable and excited about working with.

Read more: 20 greatest punk-rock vocalists of all time

When MUNA were struggling to get their head around the sound they wanted on “No Idea,” a MUNA track that sounds like a Backstreet Boys song, they enlisted the help of sad pop queen Mitski. “I love everything that she does, and I always will. I just love her. So much. I love her as a person and everything that she does. I identify with her so much,” Gavin gushes. She references the way that Mitski, who didn’t release a record between 2018 and 2022, crafts strict boundaries between her personal and public lives, rejecting the entitlement of fans and the press. “A lot of us have to learn how to not give parts of ourselves away that are essential to being who we are and doing something sustainable. I think Mitski is so brave and brilliant and strong as an individual. She’s a North Star for me.” With the help of Mitski, and their faith in her process, they got “No Idea” to a point they were happy with, the track forming a turning point for the record.

[Photo by Lindsey Byrnes]

While MUNA were left somewhat adrift after being dropped by their label, there was never a point that they weren’t working on new music. During COVID-19, the process was piecemeal and “came together over time.” “Katie is a very prolific songwriter and has written so, so, so many songs,” McPherson says. “There are ones on the album that originated years ago that ended up making it onto this record. There are ones that originated two weeks before we had to turn the record in. It was an all-over-the-place process.”

They worked with Tashian and Fitchuk in Nashville, pre-pandemic, on “Silk Chiffon” and “Handle Me,” and had Mitski’s support and “good vibes” on “No Idea” in January of 2020, but little else. “The rest were scattered about when we were capable of getting in touch with our inspiration. The process is all over the place. We’re constantly working on new music. Not right now, because we’re tired,” McPherson laughs. While the band all isolated separately for much of the pandemic, they started hanging out around mid-2020, mostly in Gavin’s backyard. They formed a pod, seeing only each other and working on the record.

I mention “Runner’s High,” a chaotic, all-over-the-place pop song that will be well at home in LGBTQ+ clubs in the coming months. “People have been very kind about that song, which I feel is one of the craziest on the record. It’s one of the wildest in terms of the way that we made it, and I am so proud of the way we made it because it did feel like we were just throwing stuff at the wall and making big choices and being comfortable doing it,” McPherson says. “We were just being a lot less precious.”

After not being able to tour for 2020 and much of 2021, MUNA are excited to take MUNA on the road. “It was years of not touring and working on the album and not really knowing how or if it was going to be released,” Gavin says. “Playing it live is the most exciting part. The best part about making music is giving it to our fans and seeing how they take it and make it their own. What they decide is a moment in the set. It’s fun and exciting, and it’s the best way to connect,” Maskin adds. “We feel so lucky to have people like our music who are also so nice to each other. Everyone is quite polite at shows and kind to each other, and it’s a good energy in the fandom, which sounds crazy to say. We’re super lucky to have amalgamated people who like our music and are also nice to one another and kind people. We feel lucky.”

In the coming months, they’ll be touring MUNA, taking in their achievements and playing their first LA Pride with Years & Years. “I’m excited for ‘What I Want’ to get its moment. It’s the big, out there pop song on the album. It’s going to be a challenge to lean into that alter ego, but it will be very fun,” McPherson says. “We’re going to try to keep busy and keep our heads on and keep growing and keep being cool.”

Despite working on MUNA for so long, it’s taken them a while to get their heads around just what it is. “It took the two years we had from 2020 until the end of 2021 when we finished it to figure out what it was. We’re still figuring it out, in a way. It’s been fun doing press about it and talking about it to people who’ve heard it,” McPherson says. Gavin adds: “We’re trying to have some fun, for sure.” After some hard times, the loss of their label and their reconnection with themselves and each other, maybe the clue to exactly what MUNA is lies in its title. It’s a reclamation of — and reconnection with — who they are, both as a band and people.

More than that, it’s a euphoric comeback.