A historic look back at the New Brunswick basement scene in the heart of New Jersey

Welcome to Scene Report, where we highlight significant, underground scenes and subcultures across the globe.

There’s a town in New Jersey about halfway between New York City and Philadelphia that’s best known as the home of Rutgers University, and where pharmaceutical behemoth Johnson & Johnson is based. But if you walk on any given night down Hamilton Street, which intersects Rutgers’ College Avenue campus and leads to the area where students opt to rent rooms in old houses instead of pricier residence halls, you might hear some noise emanating beneath a few of the buildings. In the houses just over a mile away on the outskirts of the hulking school’s Cook-Douglass campus, you’re likely to hear something, too. That is, as long as it’s before the 11 p.m. curfew.

These houses are part of New Brunswick’s storied basement music scene, which has served as a training ground for countless rock bands, including the Bouncing Souls, Thursday, and Screaming Females. For at least three decades, Rutgers students with rock ‘n’ roll inclinations and Jersey kids looking for a place to jam out in front of a receptive audience have turned to these basements to conduct shows their way.

Thursday frontman Geoff Rickly, who grew up several counties north of New Brunswick in Dumont, set out to find his hardcore brethren as soon as he arrived at his Rutgers orientation in the mid-’90s. “I really quickly found the five other hardcore kids at orientation, and I ended up rooming with one of them in our dorm the first year,” Rickly says.

Together, they tried to convince a student arts council to help invite bands to their campus. But after an unfruitful meeting with the president of the council, they abandoned the school as a means of seeing the music they wanted to see in town altogether, and started attending basement shows.

In his sophomore year, Rickly and his friends found a house to rent at 331 Somerset St. that had all they needed: rooms to sleep in and a basement where they could throw shows. Thursday exists at all, thanks to that very basement.

“The reason we started the band was just to play one of my basement shows,” he says. “More people will come to see a touring band if the local house band is playing. It’ll be more of a hangout and supporting your friends.”

For college kids, Rickly and his roommates tried to be as hospitable as they could be to visiting bands. “A lot of times they would come in a little van, they’d pull up not having eaten in three days, and I or one of my roommates would cook them pasta, or the cheapest possible meal,” he says. “We were sort of the crash pad, too. At The Drive-In stayed with us back before anybody knew who they were.”

[Photo courtesy of Marissa Paternoster / Marissa Paternoster of Screaming Females]

Hosting touring bands is pretty crucial for New Brunswick bands, because it’s a give and take. If you host out-of-towners, they will likely return the favor to you, says Screaming Females singer and guitarist Marissa Paternoster, who grew up in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and landed in New Brunswick for art school in the mid-2000s.

“We were hyper-vigilant about starting shows on time and keeping people inside,” says Paternoster, who ran shows at a house called the Parlor on Hamilton Street. “We couldn’t afford to get a noise ticket. Nobody wants to have a band from California come to New Brunswick — which is a town no one has heard of or cared about — and then have them not be able to play.”

The noise from the basement scene has long been a point of contention with the police department. They “love to break up a rock show,” Paternoster says. Madison James of Ogbert the Nerd, one of the more recent bands to come out of New Brunswick, agrees, saying they felt compelled to “[run] shows like an Army general” in order to avoid the risk of a noise complaint. It’s actually because of the scene that the NBPD enforced a noise curfew at all, which was first at 10 p.m. before it was extended until 11. That’s long been a frustration of the scene — especially since there’s a sense that the NBPD is more tune into what’s happening at house shows than at frat parties, given how little the authorities intervene with Rutgers’ just-as-loud Greek row.

Even practicing music in New Brunswick presents the threat of a noise ticket for upwards of $300. Paternoster, whose first practice space with bandmates King Mike and Jarrett Dougherty was in an attic space off campus on Ray Street where sound burst through the roof, says she did get a violation once. She says, “My dumb, little 20-year-old butt went to contest it in court. The judge was like, ‘Just pay. You have to pay.’”

Creative ways of blocking out noise always came in handy, though. That was always the case at Rickly’s house. “We would keep the shows quieter than practice was. We would have all the vans park in the driveway against the foundation of our house, so it’d be an extra layer of buffering,” Rickly says. “They’d have to get out on the passenger side, because we needed their vans to keep the sound together.”

Fire hazards were also something to consider when packing folks of all ages into small, low-ceiling basements. One night in 1999, for example, Jersey screamo band You and I played their last show at 331, and Rickly says 250 people paid to attend. “The only way to get in was by opening the storm windows, and people were lying in the driveway with their heads through the windows to watch the bands,” he says.

Mike Yannich, aka Mikey Erg who fronts Old Bridge’s the Ergs!, says playing in nearby New Brunswick to packed basements was instrumental to his band’s success. “Whenever we would play the Parlor, there would be 100 people there, no matter what — despite the fact that it didn’t hold nearly that many people. It just always felt like home,” he says.

At-capacity shows for touring bands were certainly great for exposure, but they weren’t without their flaws or down-right hazardous logistics. Paternoster says, for instance, that she was once asked to bring box fans over from the Parlor to a show at 331 Somerset that was completely packed and getting too hot inside. She says, “I couldn’t get downstairs at all. It was like everyone oozed into each other in this amorphous hot ball of flesh … I just dropped the box fans and I was like, ‘I have to get the hell of here.’”

Ogbert the Nerd even had to make the executive decision to stop playing basement shows after one fateful gig at James’ house in 2021 when the Florida-based indie band Camp Trash came up to play and 180 people showed up to what was supposed to be a 100-person capped event.

Even with the inevitable helping of disorder, though, the bands reiterate how special the shows always were. “There was some dumb punk stuff, like people puking in sinks and people falling asleep in stupid areas where you’re not supposed to fall asleep,” Paternoster says. “We never had to deal with anyone getting in a fight. There was very little violence. It was a lot of chaos, a lot of people having fun, and people taking care of each other.”

The New Brunswick scene also remains special because no one genre defines it. While there may primarily be mostly hardcore, punk, emo, and noise acts, all of those could be represented on one bill.

“The dominant form of the music at the time [in the ’90s] sounded like the Promise Ring, or Texas is the Reason. A lot of stuff sounded like the Get-Up Kids,” Rickly says. “I thought that we were one of those chaotic, dark, hardcore bands, but a little goth or something. Then later, everybody would sort of see us a different way.”

Paternoster says she was first drawn to shows the art kids were putting on, even though it wasn’t necessarily her thing. “I was friends with a couple of kids who were really into noise and performance art, so I went to a lot of these noise shows,” she says. But once she met her future bandmate Dougherty, who took her to see a basement pop punk show, she felt at home. “My life just changed. Like, that was it — I found the people that I was looking for my whole life.”

More recently, Ogbert the Nerd often stood out as the only emo band on the bills they played. “When we came around, there were rock bands. There were a lot of jam bands. There was a big emphasis on twee back in like 2019,” James says. “So everyone wanted to get us on a bill because we were doing something ‘different’ — but it’s not different. It’s just something that was made in defiance, which is like the spirit of [the scene], especially in a town like New Brunswick where it is so transient, people come and go, and there’s a new scene every four years.”

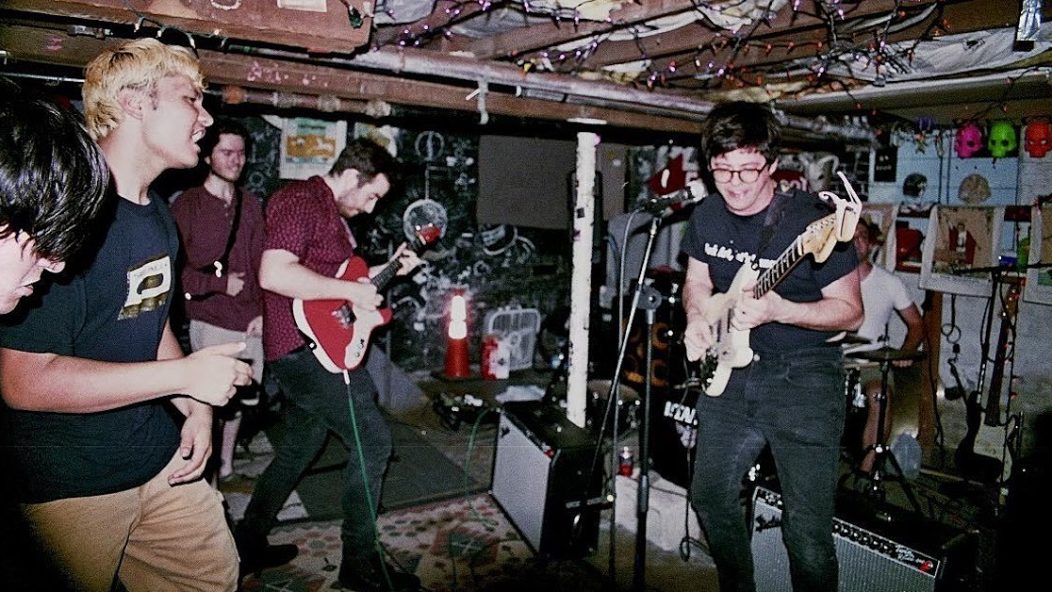

[Photo by Matt Hono / Ogbert the Nerd]

With the scene being so sonically diverse and inviting to whomever’s able to make their way to a gig, it’s always been important to bands and venues to get the word out about events.

When Thursday was in town, things were a bit different. Rickly’s roommate was more online than he was, he says, so that helped to spread the word in the early days of the internet.

He says, “I had a university email that I never checked because I thought email was a fad … He was on listservs and message boards, so he would get out a lot of the word of the shows on there, and I think that’s why people knew where our place was.”

Yannich says he remembers that shows were promoted offline as well, with lots of word-of-mouth and flyers left at the now-defunct record store Vintage Vinyl. Although, now, when you might think house shows would be advertised online more than ever, that’s not necessarily always the case in the New Brunswick scene. James, for instance, decries the current practice of making shows highly visible on Instagram. They say, “Show houses will run Instagram pages where they post flyers to shows that are happening at their house. I am of the Facebook events generation of DIY shit. That’s just such a beacon to get flagged.”

Life in New Brunswick has shaped many bands that have gone on to find a wider audience.

“It really felt like we were part of something special. There was always a place to do shows and to do whatever type of music you wanted,” Yannich says. “You didn’t have to be a hardcore band to play a New Brunswick show. You didn’t have to be a pop punk band. It was all very diverse.”

Rickly also says he was and still is grateful to have been a part of the DIY scene, which, at the time, was bigger than the one in New York City. “Even now to this day, when we go on stage, the first thing I say to the crowd is, ‘Hey, we’re Thursday from New Brunswick, New Jersey,’” he says. “It still in my mind identifies what kind of music we play.”

James says that the vibe in New Brunswick has even gone on to influence their songwriting, saying, “New Brunswick creates this feeling of insulation and if you’re not insulated, you’re isolated. That feeling really resonates … it’s a city between five major highways. You can walk across town and back and that’s about it. It makes you spiral a little bit.”

The scene was just as formative to Paternoster. She says, “I was a very fearful child, so being able to have these experiences in New Brunswick and through punk changed my life in a way that was really important and really positive … I don’t know what I would’ve done without it. I probably would just be quiet and scared in a cubicle somewhere.” A cubicle would be a far cry from the stages she’s played across the country and beyond, that only a Central Jersey community driven by dark, sweaty basement punk shows could’ve prepared her for.