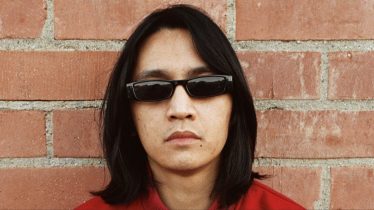

OK Go - "Another Set Of Issues" song premiere and interview

“Thank you for being my guinea pig,” jokes OK Go frontman Damian Kulash, at the end of a lengthy, but fascinating new analogy he’s just created, about the way songwriting is like a sonar device. “Now I need to get that down to a one-sentence version.”

Kulash is known best, perhaps, for his music and music videos, a series of clever clips—like the past summer’s “The Writing’s On The Wall”—that have gone viral and helped bring the band’s hook-heavy pop to the collective consciousness. But he’s also very fond of words: not just turning them into analogies, but the way they work in songs, and their inherent limitations. If you didn’t know Kulash studied semiotics (the study of how meanings are made) at Brown University, you might guess it nonetheless.

That’s not to suggest Kulash is an elitist theoretician. He cheerfully dismisses most of his college training as “pretentious academic bullshit,” and is self-effacing to a fault. On an off-day in the middle of OK Go’s current tour, Kulash fielded questions from a Cleveland hotel room. The joy he still takes in the creative process 15 years into the quartet’s career is a good indicator of why OK Go have not only survived their jump from a major label to the Great Unknown, but thrived.

Here’s Kulash on his Chicago-born, LA-based band’s new album Hungry Ghosts, the genius of Elvis Costello, how to succeed in business and the meaning of success.

Treat yourself to this AP-exclusive debut of OK Go's “Another Set Of Issues” from Hungry Ghosts as you read our Q&A with Kulash.

I understand the songs changed quite a bit over the course of recording Hungry Ghosts. In one case, you brought in a song, “The Great Fire,” that producer, Dave Fridmann, said he’d need to “destroy” if it were going to make the record. It seems like it’d take a strong constitution to hear that about something you’ve worked hard on.

DAMIAN KULASH: Yeah, it could take a strong constitution. I have a pretty nice recording studio. I have some decent equipment. I can make a record on my own. And I have a great version of that song. If I ever wanna release that, I can release it. The more finished something is, the less I have to worry about it later. We live in a fairly non-destructive world. As I’m talking to you, my computer is sitting here backing itself up from the last week. I can literally go back in time a week. So it’s really not that scary. Especially working with people that you know so well, and love so much.

We frequently get ourselves into situations where we all know that we don’t know. “Is this better than the version that we had before? I’ll sleep on it and tell you tomorrow, because I really can’t fucking tell.”

As you say, we live in such a non-destructive world—we live in a world that’s post-remix culture, where there’s always that question about when something is really “finished.” It sounds like you guys confronted that head-on with Hungry Ghosts, by recording so many different versions of songs. That must take a lot of trust, too—trying to be sure that the version you pick is the right one, at least for this project. I don’t know if a new band could survive that.

You really never know. We did, like, 10 mixes of some of these songs. Which one goes on the record almost becomes a coin flip at some point. “I like this one because it’s louder, and I like this one because it’s more sensitive, and I like this one because it makes me wanna dance more.”

We really wanna have categories that make sense. We want the music to fit in this box, the video to fit in this box, the art to fit in this one and journalism to fit in this one. But all of those categories are really arbitrary constructs, you know? It’s sort of the same with our output. Is it done? Is the Pachelbel Canon finished? I mean, Pachelbel wrote the Canon, and it’s finished—but how many rock songs are built around those same four chords? How many commercials have you heard it in? And the context changes every time you hear it. Sometimes it’s funny, sometimes it’s sad and sometimes it’s glorious. Are any of the Beatles’ songs done? They keep changing around, and the world keeps changing them around. We would love for these things to be stable ideas, but they’re not. You have to pick a line in the sand, and say, “This thing is done, and it’s going out.”

We recently worked on revising part of our live show. We’ve come up with this really crazy production that requires us to go back and listen to our old recordings as a reference point. I’m listening to stuff off our first record and thinking, “Is that really my voice? I don’t sound anything like that!” I’ve probably sung “Get Over It” probably 4,000 times in my life at this point. We play a couple hundred shows a year, and we’ve been around 15 years. But I haven’t listened to the recording in, probably, five years, because I don’t sit around and listen to my own recordings. I hate hearing them. It’s like reading your papers from college—you would never do that! But the truth is, we’ve been working on that song for the past 15 years. And I don’t even remember what the words were about—I sing them every night without thinking about what they mean. It changes and changes and changes a little bit every night. That’s what happened in the studio, just at a greatly accelerated pace.

So your semiotics training in college wasn’t for nothing. There’s some of that in what you say about these old songs, and the way they change meanings over time, and in different contexts.

Certainly. You know, a lot of what I studied in college was just pretentious academic bullshit. [Laughs.] But it did influence my thinking, that’s for sure. And a really key point was that we really wanna lock down ideas and believe that they’re stable. But they really never are.

There’s this incredible David Foster Wallace piece—I think it’s called Authority And American Usage—and ostensibly, he’s writing a book review of a grammar guide. Nothing could be more boring than that. But out of that, he manages to tease the nature of democracy and the fight between the prescriptive and the descriptive. You need to have a set of rules. You need to have things locked down. But the truth is that things are never locked down, and that’s what makes the world so beautiful. Language is different every day. You need to have a set of rules so you can understand it. But it’s also going to change all the time, so that no one can ever really understand it.

I think this is how I ended up in music in the first place. As you can tell by my rambling, I’m a classically logic-trained person. [Laughs.] Logic, logic, logic. What’s so good about music is that it completely refuses to conform to that. When it works, it’s magic. It’s alchemy. I put these two notes together, and instead of two notes, I got fury and lust and melancholy and joy, all at the same time, this insane burst that doesn’t make any fucking sense. That’s what’s so beautiful about music.

When someone interviews you, there’s a lot of stuff to talk about—the videos, the extracurricular activities. How often do people ask you about lyrics? It seems like that’s something that could get lost.

I do spend time talking about lyrics. You’re right—there’s a lot of other stuff to talk about. But to tell the truth…I hate—I hate—writing lyrics.

Why?

Because of what I was just saying. When music works, it’s doing something that language can’t.

You know that Beatles song, “Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except Me And My Monkey”? When that song starts, those three chords and that drumbeat…for me, at least, there’s this explosive universe. It’s joyful but it’s tense; it’s dancey, but it’s angry. It’s about so many things at once. If I had written that song, and then had to answer, “What is this song about?” That song is about so much! And it’s also about nothing, y’know? As soon as you put language to something, it becomes reduced.

So I hate writing lyrics, because when we’ve been successful, it’s because we’ve been doing more than words can ever say. It funnels it down to one literal interpretation.

Now, having said that, a good set of lyrics adds yet another dimension to that whole ball of emotion. Like…I don’t know how Elvis Costello writes. But do you know that song, “I Want You”?

Yeah.

So I’m assuming he sat down at a piano and wrote it. And I’m assuming that he had a melody before there were words. There’s that line: [Sings.] “Since when were you so generous and inarticulate?” He manages to take heartbreak and distill it into 14 syllables that are so specific that you know exactly what he’s living through, and so expansive that you can apply it to your own life. Does that make any sense?

Yeah, you’re talking about that sweet spot every writer is going for—the midpoint between the personal and the universal.

Exactly. Exactly. Like I said, I hate writing lyrics. But I need that human in the song. I would never listen to the song “I Want You” without Elvis Costello singing it. The instrumental version of that would not be as interesting to me.

So that’s where the fight is. Can you actually land in that tiny, tiny bullseye? Where you’re not hiding—you say exactly what you mean. But it’s not restricted to that one meaning. “Since when were you so generous and inarticulate?” I can’t think of an ex-girlfriend that that line doesn’t describe. [Laughs.]

This is not a metaphor. There’s no veiled meaning. He’s saying exactly what he fucking means. And yet it’s bigger than that. It’s like, how many people have ever sung the line, “I want you.” It’s in two-thirds of the fucking pop songs ever written. It’s the most clichéd thing ever. And yet when somebody means it that intensely, and can follow it up with “Since when were you so generous and inarticulate?” Holy shit. They’re singing about what I’m going through, and what you’re going through, and what everyone’s going through. Fuck! It shakes you to your bones. And then these lyrics, which are such a pain in the fucking ass to write, went from being a few nice chords to a verse of the Bible.

Okay, so how many times have you landed in that bullseye?

Uh…zero? [Laughs.]

What’s the closest you’ve ever gotten, then?

The closest…“Before The Earth Was Round,” off the last record, those lyrics were pretty good. I think “The Great Fire” is the best set of lyrics on the new record. And there are moments…I mean, I’m also probably the worst judge of this. I wonder if Picasso looks at Picasso and sees Picasso, or if he just sees brush strokes.

To me, I remember the fight with every line of these things. You’re asking which lyrics work, and I’m telling you which lyrics came easily. ’Cause when this is all working, that’s when I feel like I’ve succeeded. If I fight for six months with a bunch of words…they might work in the end. But I would never know.

You mean you like best the songs that seem to come almost fully formed.

Yeah. On most records, there’s one song where that happens. Now that I’m thinking about it, it’s usually a ballad. There’s one song on the second record…hold on a second. [Sings to himself, then gives up.] I’ll have to look them up, because I can’t remember my own songs. [Laughs.]

I read a piece where you described this record as dealing mostly with relationships. Certainly, something like “The Writing’s On The Wall” could be interpreted that way. But is that too reductive?

Well…this is kind of a cop-out, in a way. But what songs are not about relationships? I mean, it’s always about relationships, you know?

But I’m always surprised at how other people interpret these things. “This song is so uplifting and hopeful!” No, that song is angry and depressing. But relationships are exactly that confusing.

There’s a filmmaker who was documenting us in the studio, and he interviewed all four of us separately about “The Writing’s On The Wall.” And the funniest moment is when he’s sitting there talking about this—and [bassist] Tim [Nordwind]’s talking about what inspired the demo of that song, and [guitarist] Andy [Ross]’s talking about the death of a relationship, and then [drummer] Dan [Konopka] is like, “This is a breakup song?” [Laughs.] We’ve probably played that song 100 times in the studio at that point. But relationships are universal, and then they’re small and confusing at the same time.

But each song exists in a universe all its own. There’s no narrative when you’re writing. And then when you’re done and you listen back to them, it’s like, “Oh, wait—this is really a reflection of who I am right now. Holy shit!” [Laughs.] It’s like looking at a photograph of yourself from five years ago or something. At the time, it just looks like you. But now it looks like such a different person.

Is it too reductive to call it a relationship record? Well, everything is a relationship record. And about this record…I don’t yet know. Personally, I just went through a really shitty breakup, most of which happened after the record was written. When I listen to the album, I hear this stupid me, that didn’t know what was going on. But then I listen, and I realize, holy shit, I really did know what was going on. Because I’m talking about it on the whole fucking record!

It’s like your subconscious is a lot more perceptive than you realize.

Yeah…I’ve never done a very good job of describing this, but I have a really clear picture in my mind of how our writing process works. We throw a whole bunch of stuff out there—it’s like sonar, where there is an object, it bounces back at you.

I imagine bands like the Strokes, or the Pixies, or the Cure—bands that have a really consistent sound on each record—I assume those bands have a process that is very consistent, and they keep making the same sounds. Our process is very different. Our process is, make as many different sounds as you possibly can—and most of them suck. [Laughs.] And one out of a thousand, or one out of a million sounds, bounces back to you. And it means something. It’s resonant. At the time, while we’re writing, it feels like, “This is good.” It’s like the difference between the meaninglessness of sound, and the meaningfulness of music. You realize later that you’ve really made an image of yourself at the time. All the things that hurt you, all the things that made you happy—those are the things the sonar bounces off of.

We just as easily could have made a super-angry punk record, if we happened to be super-angry punks right now. I know that sounds like a tautology, but it’s not, in the sense that we don’t set out to make songs that mean X. It’s like, throw a whole bunch of stuff out there. Whatever bounces back at you will make a very accurate reflection of who you are then, whether you like it or not.