Orville Peck proves that country and punk are more alike than you think

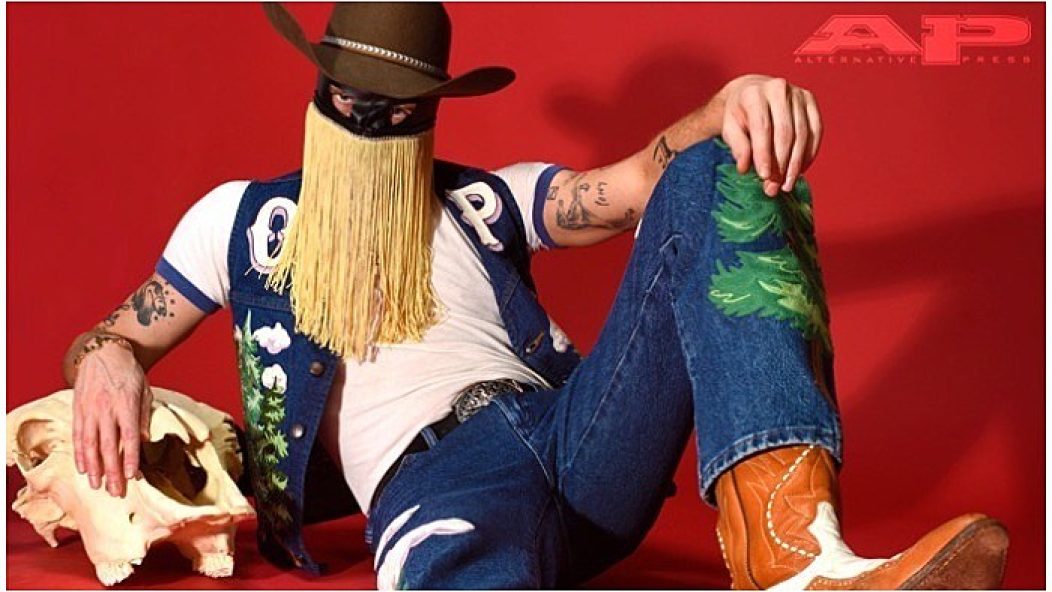

Even if you’re unfamiliar with country-western music star and LGBTQIA+ icon Orville Peck, you’ve seen him: bright blue eyes striking through a leather-fringed mask, enticing an audience with a costume that he describes as “the boldest version” of himself. Since 2019, Peck has taken classic country music and made it his own by adding elements of shoegaze, dream pop and indie rock to queer heartbreak songs of such sincerity, they’d make an old crooner cry. Call it goth, call it cowboy, call it alternative, call it whatever you want. Peck is quintessentially himself—and the future of country music. And did we mention that’s not even his real name? Now that’s punk.

Read more: KennyHoopla is keeping busy dreaming up your next favorite song

But who is he? Peck keeps the personal details of his life private—he’s in his 20s, or 30s, or 40s, he’s lived in South Africa, Canada, the U.S. and the U.K. but cites a “Southern Hemisphere” upbringing spent obsessed with Dolly Parton in most conversations. Every inch of his being is laid bare on record, and exposing his lore only distracts from the velvet richness of his sonic heartbreaks, the melodrama of his most existential songs. You don’t ask a magician to see his tricks, and you don’t ask a country musician to drop his fringe mask.

You are the first country musician to be featured on the cover of Alternative Press. Congrats!

Thank you. I grew up playing in punk bands and loving rock music—just being a little weird alternative kid—so Alternative Press was always a staple for me. I remember I used to skip gym class to go to the local library and grab Spin Magazine, Alternative Press and Rolling Stone and read all of those. I’ve always loved Alternative Press because it has always encompassed so many facets of subversive culture, whether that be music, art or tattoo culture. It’s always been a great representation of otherness, which even speaks to my place within country music.

The fact that this conversation is taking place reflects some shift in culture: Alternative music is an ethos, not just a word limited by genre. Do you consider yourself an alternative artist?

I consider myself a country musician, but I definitely see people framing me as alternative by today’s standards. [My music] pulls references from all kinds of genres, so maybe that confuses people. The irony is that I make music that sounds similar to what I would consider “classic country” more than what country music sounds like today. And I’ve always had an alternative spirit. I come from the DIY space. I grew up listening to all kinds of music. So it doesn’t bother me.

There’s so much mythology surrounding you, and some of the most iconic alternative artists in AP’s history also exude some magical mystery without being intimidating—call it David Bowie’s influence, whose real name was not David Bowie and who many people thought was an actual alien. Is that a hard balance to crack, being bold and out there but also accessible?

The punk musicians of the early ’70s—I think of the mask scene in Los Angeles, the Germs and X and the Screamers and all those bands—they all had crazy stage names. They all wore costumes. But they were singing about deeply personal, edgy things. I think someone like Bowie is a great example of that—very theatrical but still writing very evocative, heartfelt music. That is inherent in country music, especially the era of country music that I love. So, it’s not really a hard balance because I think the key is to be as sincere as possible, to be as personal as possible, with the music that I write, and that allows me to get away with being as theatrical as I want. You have to have a little bit of courage to put yourself out there, in a lot of ways.

The mask. You’re never pictured without it. I’m glad you didn’t try to capitalize on it during this pandemic by producing mass face masks or something because that might alter its effect. How has this year, if at all, influenced your feelings about mask-wearing or your visual aesthetic as a whole?

I’ve been asked about it a lot in the last nine months. My mask—there’s so much meaning in it for me, and I don’t talk about it because I don’t like to take away whatever it might mean to somebody else. I’ve heard so many different interpretations about why I do it—some of them good, some of them bad—and they’re all valid. I hate explaining or spoon-feeding anything to anyone because as a fan of music and art, I like to involve my own take on it. That’s the reason I don’t really pin it down, explain it or talk about it. I just like to let it be. If I were to make a line of COVID masks, it would be very contrary to what it means to me. But I do appreciate that people have been making their own COVID masks with fringe on them. I get tagged in a billion photos a week with “Orville COVID Masks.” I really love that.

I was going to ask what the significance of wearing a mask is to you, but it sounds like it’s the freedom to allow others to ascribe their own significance upon it.

You got it.

Is there something freeing about wearing the mask? I’m not saying you’re a character—but it’s a performance. Is it a liberating one?

The misconception is that I wear a mask to allow myself to be myself, in that it provides me with anonymity. But that’s not really the case. I think that wearing a mask is really exposing, in a lot of ways. It actually makes it harder to go onstage and be sincere because it comes with a misconception from people that maybe it is a gimmick, or it means that what I’m doing is a joke or a parody. But the reality is that I’m a country-western star, and I grew up loving huge colorful characters within the genre. This is the amplification of who I am, deep inside my core, and this is what it looks like. It could have been anything, but this is what it was.

And masks hold that power. You frequently draw comparisons to The Lone Ranger—characters from old Western films—where masks allowed for freedom through anonymity. Is that an idea you’re attracted to? Not necessarily hiding—you’re not—but an image synonymous with an anti-establishment way of being?

I’m the kind of person who really struggled to go to school and to finish school because I hated authority. I hated being told what to do. I liked to learn on my own because I thought I could do it better by myself, in my own way. I’ve always been someone who knows what I like and wants to do it, and I don’t really like being told how I should do it, especially if someone is telling me how I should do something. I usually want to do the complete opposite. There’s, of course, an element of subversion in [mask-wearing], but ultimately, I just don’t want to be boring. And I’m bored by most stuff these days. If I’m going to make music, and I’m going to charge people money to come to my show and go and buy my record, I don’t want to bore them. I want to do the biggest, boldest, most creative and sincere thing that I’m capable of because that’s the kind of stuff that I like to enjoy. Basically, the bottom line is, I don’t want to be boring, and there’s so much boring stuff going on.

There is a belief, more prevalent from outside country music circles than from within them, that country music is overwhelmingly conservative and therefore lacks subversion, and that’s why you are noteworthy. I tend to see it as the opposite—you highlight and remind listeners of the rebelliousness that exists in country music. Do you see yourself as an extension of that subversion?

Absolutely. All of my favorite country musicians, at one point or another, were being criticized in the country world for not being “true country.” Willie Nelson. Johnny Cash. Everyone. The outlaws, before them, country music was essentially completely conservative and, most of the time, based in religion or conservative values. Then the outlaws came, and they brought this whole hippie culture into country music, and a lot of people didn’t like it. They said it wasn’t country. The same thing has happened to plenty of people. Shania Twain was telling me about the struggles even she had when she first came on the scene in Nashville. Everyone was telling her she wasn’t country because she was showing her stomach and singing songs that they felt didn’t fit into the country world. Everybody goes through this. So I think the fact that I get any kind of criticism for “not being country” means that I’m on the right track.