Bloc Party - Intimacy

Bloc Party

Intimacy

Bloc Party’s 2007 album, A Weekend In The City, did a fine job of polarizing the audience they had amassed on their Paul Epworth-helmed debut, Silent Alarm. Producer Garret “Jacknife” Lee laid on the electronics nice and thick, giving singer/guitarist Kele Okereke some new launch points to move forward from, but the band’s propulsion and energy were significantly downplayed in favor of funny noises. Ironically, both producers hold court on Intimacy, which means listeners still get funny noises, but they’re couched in some of the quartet’s most vibrant songs and decidedly unhinged performances.

Surprisingly, those deranged moments are top-loaded at the beginning of the album. “Ares” is an abrasive rave-up where processed guitars fight with electronic noises as Okereke passionately rants, “We dance to the sound of sirens.” The streamlined but no less reserved “Mercury” finds the singer dismantling a relationship on a bed of horn samples and drummer Matt Tong’s relentless time-keeping. (The track is the bastard grandchild of Public Image Ltd.’s “Careering” and “This Is Not A Love Song.”) Tracks like “Halo,” “Trojan Horse” (with the indicting line, “You used to take your watch off before we made love”) and “One Month Off” find the quartet maintaining the energy found on Silent Alarm, while augmented with significant electro-crunch. Even when the band dial it down a few notches (the music box chiming of “Signs” and the hip-hop programming of “Biko”), there’s still a defined personality coming through, unlike, say, OneRepublic. Intimacy is arguably Bloc Party’s finest moment thus far, offering sweat and circuitry, savagery and submission, and a captivating energy that’s severely lacking in many music scenes on the planet.

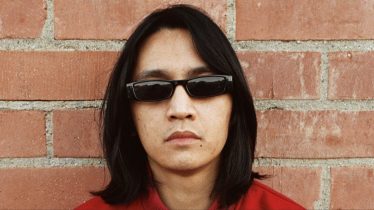

IN-STORE SESSION WITH FRONTMAN KELE OKEREKE

It seems like Paul Epworth focuses on capturing the dynamic of a live band, while Jacknife Lee has a fondness for sonically chrome-plating everything with electronics. Why use two seemingly different producers for one album?

The last track we recorded on A Weekend In The City was “The Prayer.” It was a real kind of milestone where we realized there was a lot more mileage in this way of working and we could be a lot more adventurous with instrumentation. Weekend is a much more contemplative, integrated record, and we wanted to capture some of the live energy that we were kind of famed for. It was a case of making a record of two halves and trying to blend them together. I think we achieved that; [critics] have an idea of which producer did what but they have it wrong. My only concern was that there was a real cohesion.

Drummer Matt Tong is Bloc Party’s not-so-secret weapon, and this album seems much more rhythmically urgent than the previous two. Were you specifically writing things that emphasized rhythm more than the previous records?

The rhythmic aspect has always been an important facet. It’s how we write: I’ll start with a riff and try to give Matt a direction of a beat I’m hearing in my head, and he’ll take it somewhere else. Unlike most bands who start off with something on an acoustic guitar or keyboard or something, the rhythmic aspect is the most important to me. I can get off on music some people might not like simply because the beat is always good. I went to see Björk in London, and at the end of the performance, I realized that I wasn’t listening to her-I was listening to the rhythms. I was actually blocking out her voice, which, I think is the thing most people go to her shows for.

“Mercury” and “Ares” come off as a jarring one-two punch. Was that a conscious decision to shake up listeners’ pre-conceived notions of what your band “should” sound like?

That’s been my objective from day one, really. Silent Alarm was a reaction to people who had us pegged after hearing the first EP. Weekend was a reaction to people who pegged us after Silent Alarm. With this record, we’ve come to the point where we’re more comfortable with what we’re about now, that we feel we can do anything. That sounds arrogant, but I don’t think it’s a bad thing in pop music to be so reverential about “pop form” and structure. It’s good that people want to fuck shit up-it doesn’t really happen enough.