Rhys Langston is putting rap everywhere

Welcome to AP&R, where we highlight rising artists who will soon become your new favorite.

A strange combination of words is all it takes. Time capsules swallowed and crumbling RAM chips conjure images that open up a wormhole to another galaxy. In this unknown future, communication is fraying at the edges, but DoorDash may as well be delivered through a crystal-clear tube. For all you know, Genius no longer exists to immortalize Rhys Langston’s indelible flow.

You can’t make six albums filled with intricate and daunting raps without being fascinated by language. The impressionistic indie rapper twists and recalibrates words as he sees fit, stringing together mesmerizing verses that require several spins to unpack. Over Zoom, he’s far less formidable, exuding a warm presence and easy smile. His love for the form shines through. He’s also a voracious reader. His latest triumph is finishing Haruki Murakami’s thousand-page opus 1Q84, and he’s already halfway through another book. But Langston has a lot more to say, as spitting raps is only one shape that his words can take. He also pens poetry and prose and journals regularly.

Read more: With If Looks Could Kill, Destroy Lonely made the ultimate “sonic horror movie”

“I don’t say that to flex,” he says from his home in Los Angeles. “But it’s a central tenant and core of how I operate. I find that writing raps is just one form that the writing takes, and that helps me not feel like I have to say everything in [those].”

Langston is a rapper constantly in flux. Whether he’s unfurling dense verses about graying poets or getting to act like a frontman, like he’s accomplished with intergalactic duo Pioneer 11 on their new album, To Operate This System (out July 26 via POW Recordings), you can bank on the LA eccentric to do the unexpected and push the boundaries of hip-hop.

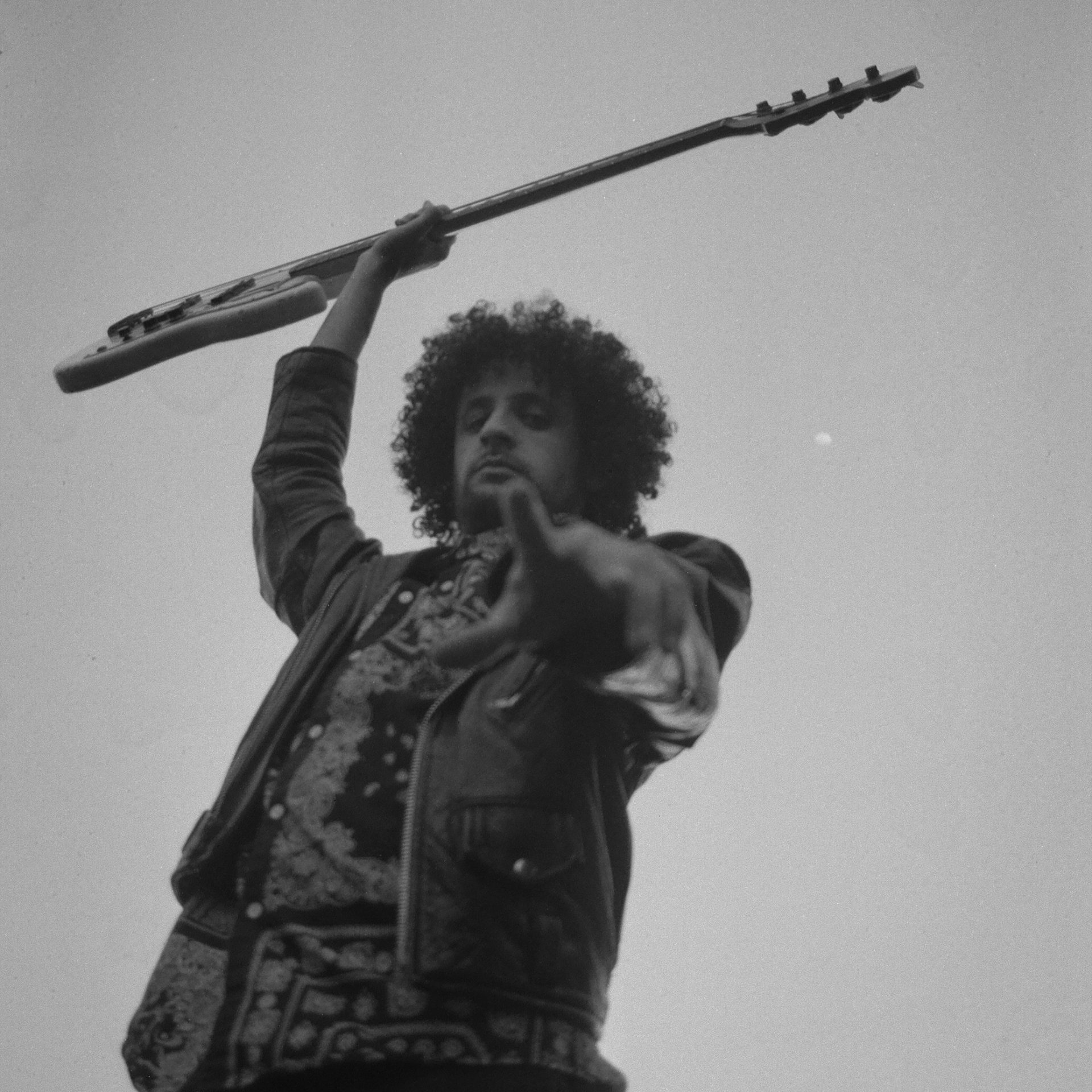

Photo by Emily Berkey

Heading further into the unknown is what sets him apart from his contemporaries. On his latest, Langston has traded in his usual blitz for futuristic psychedelia that often pares down his words and employs more melody. The project is wholly distinct from anything he’s done yet. “I’m sorry, I’m not going to be a sad cis man rapping over dark beats,” he stresses with a laugh. “That’s done by these guys. It’s pretty sick, not me. I’m trying to be goofy and sing about my cat in space.” He’s profound and singular in that sense. The algorithm just hasn’t caught up yet.

Pioneer 11 clearly travel in the same orbit. The duo of Bryan Gomez and Alex Hastings, named after the first spacecraft to reach Saturn, lean into the strange and experimental. The band create the type of warped space funk that will make you feel like you’re barrelling through another planet without ever stepping beyond your living room (DMT has the same effect; it’s your choice). Together, the trio make cuts that bubble with imagination and levity, sharing production credits across the whole album. They imagine a future where Massive Attack live in the same room as Dorothy Ashby. Everything’s melting. Sometimes the three morph into one. “Their willingness to work and blend in so many ways, inherently, is what made it so easy,” Langston says of the collaboration. There’s nothing new under the sun, but these interdimensional wayfarers, whose disregard for convention and celebration of possibility shines bright here, craft music that casts a unique impression. This is rap for people who like hallucinogenics, Beat poetry set to Mellotron, and your invitation to raves on the outer limits.

It’s easy to picture the three in the studio together, heads bowed as they carve out a new future for themselves. Convening at bassist Hastings’ house in West LA with a live looping setup, they would lay down parts and then subtract and add as needed. There was always a vocal mic present. “Their setup really brought out more spontaneous and live elements to composing music, whereas working electronically, especially by myself, sometimes the loops themselves can become like you’re literally caught in a loop — [you’re] trying to get out or trying to find some other color,” Langston adds. In the case of “The Story of the Three Surveyors,” a tale about travelers on a mission of grave importance that unfolds over a sci-fi beat, they “jammed out that whole thing.” They created the drum parts together, and Langston dreamed up the melody on the spot. Whatever the reason, though, the room possesses a sense of magic. “Whenever I step into that space, I become way better at playing the keys,” he says. A certain distance from your home self is everything.

If you’re new to Langston’s zany brilliance, you’d be forgiven for not appreciating the album’s biggest departure — his vocal chops are on full display. “I’ve been hiding my voice for a very long time,” Langston admits, as the rapper has been singing since he was a kid. “My parents, if you ask them, they’d be like, ‘Oh Rhys has always had a wonderful voice.’” Here, his approach to singing is languid and soulful. On the opener “On My Own,” Langston glides against a ghostly beat while synths hum behind him. Other times, he straightens his back and sounds as if he’s in the midst of smoking his opponents in a poetry slam, like with “DoorDash The Basilica.” Though he’s sung hooks before, it was more about using his voice in a way that didn’t feel “stuck on, glued together, or like it was forced.” It’s also opened a passageway to create music that transcends his rap roots.

“I finally feel like I’m able to start making all the kinds of music that I’ve been interested in,” he beams. “A lot of the music is not explicitly hip-hop or electronic — being able to veer into alternative spaces, soulful spaces, R&B spaces. Maybe not quite jazz yet.”

Perhaps the transition doesn’t feel as stark because, in a sense, Langston has embodied the qualities of a frontman all along. The signs have been there: On past projects, the speed at which he delivers his verses mimics that of a hardcore band. His love for rock gleams with shoutouts to Living Color’s Vernon Reid and nods to Suicidal Tendencies on Stalin Bollywood cuts. There’s a TV on the Radio cover within that same record. “When I started out, I was never able to be in a band or play instruments that well with other people,” he says. “It’s a nice way to ease into that as I have more musical vocabulary that I’ve acquired through trial and error.”

Photo by Emily Berkey

He’s profoundly alternative in that sense, showing no hesitation when asked if that’s an accurate descriptor. In a way, his music offers a bridge. It’s just a matter of accepting the invitation and crossing over. “I’m trying to put rap everywhere possible, tastefully,” Langston says. “In terms of alternative, it’s been categorized as a sound for so long, but it’s more of a disposition and more of an outlook than anything else.” It is indeed a state of mind, as well as something that has been corrupted by aesthetics. “It’s very hard to really have alternative mean something,” he continues. “You don’t have to go full anarcho-communist, but I do feel like it’s a willingness to break out of certain molds and be resistant, even if you have to be obnoxious about it.” He cites Saul Williams as an example, whose 2004 cut “List of Demands (Reparations)” confounded thousands when it landed in a Nike ad over a decade ago. “Selling out” may just be the lowest form of shock value when the cents are calculated per stream. “When the pendulum swings from avant-garde to convention, it’s the duty of alternative artists to piss people off a little bit,” he says. “Ideally, you do something different that people resonate with.”

Langston may not be provoking his audience with audacious tweets, but he occupies his own unique lane. He will never make the same album twice. He is divergent in that sense, lurching away from what he’s already achieved and embracing unpredictability at every turn. The jazz record may be a long way off, but like anything that Langston does, the possibility is simply a thread waiting to be pulled. “I’m not gonna say anything, but don’t be surprised,” he laughs.