Was the Sex Pistols' first US tour as destructive as reports say?

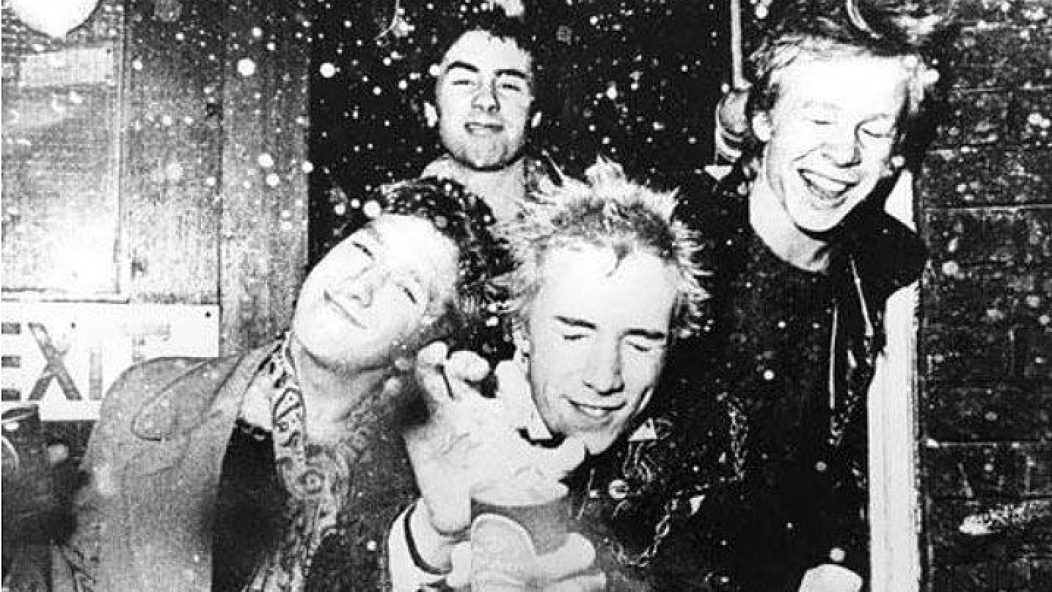

[Photo by: Sex Pistols/Facebook]

“Ah, ha-ha,” chuckled Johnny Rotten, crouching in front of Paul Cook’s drum kit. “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated? Goodnight.” Then he stood up, took a final look at the crowd and followed bandmate Sid Vicious into the wings of San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom. It was nearly midnight, Jan. 14, 1978. The Sex Pistols were in tatters and, four days later, Rotten quit. For years, these seven seconds have stood in for the seven gigs of the Pistols’ 1978 American tour, as if every concertgoer from Atlanta to San Francisco were subject to the greatest rock ’n’ roll swindle. Bollocks. At the five shows between Atlanta and San Francisco, the Pistols offered—in the words of rock critic Dave Schulps—“one of the best rock ’n’ roll shows I’ve ever seen.”

READ MORE: Son of Sex Pistols’ manager actually burns $6M of rare punk memorabilia—watch

Most of the rock scribes who saw pre-Winterland shows drew the same conclusion. Still, to the victors go the spoils—and manager Malcolm McLaren manipulated the media brilliantly. Almost always, McLaren preferred the legend to the truth, especially when the legend portrayed him as a mastermind of propaganda and the Pistols as no-talent, foul-mouthed yobs. The historical record suggests that—in spite of the absurd mileage between gigs, McLaren’s indifference and Vicious’ self-immolation—the Pistols channeled their angst into great live shows right to the end. Thanks to YouTube and the digitalization of bootlegs from the tour, we can assess for ourselves the merits of the Pistols’ performances.

The Prelude and the Aftermath

In late 1977, McLaren assembled the most improbable of U.S. tours: from Atlanta (Jan. 5) to San Francisco (Jan. 14), with gigs in Memphis; San Antonio; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Dallas and Tulsa, Oklahoma, in between. McLaren’s disdain for New York and Los Angeles led him to deliver the Pistols to “real people,” ripe for fresh confrontation—one of the few points of agreement for McLaren and Lydon. “We don’t expect everyone to understand what is going on straightaway,” Lydon said. “We’re playing these cities because these are the people who will either accept us or hate us; they’re not as pretentious as they are in New York.”

For Jon Savage, the British author of England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock And Beyond (1992), the band peaked during the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in June 1977. Afterward, “the Sex Pistols’ subsequent career was a long, slow retreat,” Savage noted, “…although they would always carry a trace of the power they had had at the time.” That power was on full display at select U.S. shows—and proved seductive, even for Lydon, who was unwilling to let it slip away quietly after the Winterland show. The following night, Lydon sought out Steve Jones and Cook and suggested, “‘Let’s get rid of McLaren,’” according to Jones, who was unmoved, and eager to join McLaren in Rio de Janeiro. “There was a lot of needling going on between the band,” Jones lamented. “It was horrible. It used to be a laugh.”

It was a brilliant laugh as late as Christmas Day 1977, for a two-show benefit in Huddersfield for striking firemen and their children. At the matinee show, after the Pistols served up slices of holiday cake to the young audience, a handful of kids smashed handfuls of cake into Lydon’s face and hair. “It was heaven,” Lydon recalled. Just weeks later, though, members of the Pistols returned from their U.S. tour on separate flights—and on separate record labels.

Lydon, too, spoke kindly about his original bandmates with Vivien Goldman of Sounds in late January. Of Jones and Cook, Lydon says, “I don’t want to put anyone down in the band because they’re all right really…The fact that I know their weak points and they know mine is fine because we don’t use them as weapons against each other. I liked working with the band—let’s face it, that was my chance, and they gave it to me.” Lydon’s wistfulness evokes the gigs from Memphis, San Antonio and Baton Rouge, when the Pistols wielded more than a trace of that power for American audiences. Let’s take a closer look at these three gigs.

Jan. 6, Taliesyn Ballroom, Memphis, Tennessee

The band opens with a scorching version of “God Save The Queen,” with Jones and Cook in especially strong form, and segues into “I Wanna Be Me.” As the raucous applause subsides, Jones tunes his guitar, and Lydon turns his attention to the audience: “Is it true you’re all into Dolly Parton down here?” The crowd responds with a roar of approval. If Lydon’s teasing offers the prospects of rapport, Vicious short-circuits it with a curse that rhymes with “clucking runts,” heightening the aggression and enthusiasm ahead of the teen-angst anthem, “Seventeen.” The Pistols’ set list included all the tracks from Never Mind The Bollocks, “Belsen Was A Gas” and the Stooges’ “No Fun,” and varied little for the next five dates.

Schulps, for Sounds, wrote with effusive enchantment about the performance.

“Johnny Rotten leered manically into the mass before him, his eyes like twin knives cutting a path through whatever was in their way, and danced spasmodically … And Sid Vicious, his shirt off to reveal a well-slashed and scarred chest, constantly spat on the stage, occasionally jumped up like a kewpie doll in shock treatment … And of course, there was the music. That too was brilliant—Paul Cook, Steve Jones, and Sid provide a solid, powerfully rocking base. And Johnny, providing the visual focus, spitting out his vocals in a style that goes hand in hand with his tragic/comic presence.”

Schulps imagined, too, that the crowd shared his enthusiasm. “Most of the audience, who were standing on their chairs from the outset, seemed to agree, reacting wildly to every move they made.” New York Rocker’s Howie Klein agreed, in slightly muted tones, out of respect to the angry ticket holders denied entrance to the ballroom who were roughed up by the Memphis Police. “Inside the hall, the Pistols were also enjoying themselves, as was the audience,” he wrote.

Jan. 8, Randy’s Rodeo, San Antonio, Texas, via Austin, Texas

By San Antonio, the ratio of media to Pistols fans had improved considerably, and the band responded brilliantly. “That show in San Antonio is one of the best rock ’n’ roll shows I’ve ever seen in my life,” photographer Joe Stevens gushed. “Rotten was in top form; the boys had put it out; the kids were going completely nuts.” In “New York,” Rotten didn’t so much as sing as denounce:

You better keep yer mouth shut…

I think about time

You changed your brain

You’re just a pile of shit

You’re coming to this

Ya poor little faggot

You’re sealed with a kiss

After the Memphis show, Schulps noted, “Maybe that’s what’s so great about this band. They strike you on two emotional levels and do it better on both than anyone else.” Well, Lydon could, but Vicious, alas, lacked such finesse, shouting, “You cowboys are all a bunch of faggots!” The crowd’s response included a full-beer-can projectile, which Vicious absorbed with his mouth (then asked for more). When a cowboy breached the footlights to defend his heterosexual honor, Vicious tried to crown him with his bass, but it glanced off the instigator and whacked a Warner PR guy instead. The Texans were impressed with Vicious’ resilience and, according to PUNK’s John Holmstrom, “Then they started throwing things for fun. Johnny got a pie in the face. After the show, you couldn’t see the stage for the beer cans piled on it. I’ve never seen such a mess, and the Pistols loved it.” Roberta Bayley, photographer for PUNK, regarded the San Antonio as her favorite, too—although too dangerous to photograph the band up close. “Sex Pistols Win S.A. ‘Shootout’” read the top headline in the next days’ San Antonio Express, and described how “a pie in the face was exchanged for a whap with a bass guitar.”

With McLaren’s appetite for violence sated, even he deigned to offer a favorable review: “I thought San Antonio was great.” The recording from the soundboard, though, preserved little more than their energy, and for good reason, according to road manager Rory Johnston. Johnston tells AP that he initially sought shelter from the hailstorm of beer cans and bottles behind the amplifier stacks. “There was a local constable there, too, and a full can came right over the top,” Johnston says, and it clocked the lawman in the head. “He kind of staggered, and I thought, ‘Oh no, he’s got a gun,’” Johnston tells AP, and he subsequently made his way around the crowd to check on John “Boogie” Tiberi at the soundboard. “Boogie was mixing the show…[but] there was no one at the soundboard.” Tiberi had apparently valued his own safety over bootleg posterity.

Johnston says he gave the devotees and would-be vigilantes the benefit of the doubt. “They wanted to emulate what they thought the punks were doing in the U.K.,” he remarks. “They were trying to figure out what people did. They were making it up a bit as they went along.” Likewise, a local entrepreneur harnessed that desire to turn rebellion into money. “People were selling safety pins that weren’t real safety pins,” Johnston says, laughing. “You could attach them to your ear without sticking them through your ear.”

After the concert, for the benefit of the film crew trailing the Pistols, the nearly concussed cowboy exonerated Vicious: “He knew I meant physical harm. And I have to say I was ugly about it.”

Jan. 9, the Kingfish Club, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

This bootleg is a favorite: The band’s in fine form and good spirits, and the clean sound suggests that the sound guy maintained his post for the entire show.

A rowdy crowd cheers and shouts as Jones and Vicious plug in. “Throw something at them!” yells a fan, and Jones strikes the opening chord of “God Save The Queen,” igniting wild applause. After “I Wanna Be Me,” the tape indicates that bona fide fans of the Pistols had worked their way close to the stage. One shouts a request for “Holidays In The Sun.” There’s a warm response to the sing-along friendly “EMI,” and, after “Bodies,” Lydon teased the audience, shushing them repeatedly. The previously ragged “Belsen Was A Gas” sounds amazing, with impressive menace in equal measure from Lydon’s voice and Jones’ guitar. Even Vicious stays in sync with Jones and Cook, and the band cuts out on the same beat in unison. The recording reveals a fan asking, “Hey, what was that song?”—a legitimate question, since it was a tune from Vicious’ days with Flowers Of Romance (a pre-Pistols band whose name was used as a title for the third album by Public Image Ltd., Lydon’s post-Pistols outfit in 1981), and had yet to be pressed on vinyl. Another fan shouts out “Steppin’ Stone” by Paul Revere And The Raiders—a staple of their live shows in the U.K., but still a baffling request, considering the Pistols’ version wouldn’t appear on vinyl until 1980. (The truly devoted U.S. fans read the U.K. music magazines, and it’s possible this gentleman recalled Morrissey’s 1976 review of the band in NME.)

After “Problems,” a fan shouts, “Nice playing, boys. Here’s a couple nickels for you.” Lydon responds to the shower of coins hitting the band and the stage: “If you’re going to throw money at us, make it dollar bills.” The ersatz hecklers cheer loudly at the opening chords of “Pretty Vacant” and sing along with the chorus. At the bridge, Lydon emphatically avows, “We don’t care!”—while the band charges defiantly on, as if their lives depended upon it.

Lydon demands patience once again and with dismissive assurance says, “This is the last one you lot are gonna get.” A rousing version of “Anarchy In The UK” follows, with new U.S.-centric lyrics. The band departs and returns to the stage for a blistering encore of “No Fun” and “Liar”—as if to confirm Lydon’s point, who politely punctuates their exit: “That’s it, because I’m too lazy to do anymore. Goodnight.” A good night, indeed: This recording offers sound testimony that provocateurs on both sides of the footlights had plenty of fun.

When asked about the audience, Holmstrom told AP, “There were women there. There were groupies at the bar…The Pistols were able to attract women. Heavy metal shows were 100 percent male.” Despite a few rough moments—“some people got the shit kicked out of ‘em by the bodyguards,” Holmstrom recalls—Kingfish ownership was happy with the Pistols. “The owner of the club was thrilled to have the band,” Holmstrom says. “I was stealing a poster off the wall, and he lent a hand. The crowd was drinking and having fun. It was a really strange tour that way.”

Coda

In the documentary The Filth And The Fury (2000), director Julien Temple sought to portray the Pistols’ history from the band’s point of view, in order to counterbalance the McLaren-centric narrative of The Great Rock ’N’ Roll Swindle (1980). With the footage from the U.S. presented in cinéma vérité, Temple seems to regard the Pistols as caricatures of themselves, slouching toward oblivion. (American critics, though, enjoyed even Winterland: “It was just amazing!” Klein told AP. “It was very, very, very loud. It wasn’t about precision playing of instruments. It was something else, and it certainly captured me.”) Savage, meanwhile, in his 1978 review of bootlegs from the tour, describes the Winterland show as “appalling and hysterical…the band are all over the place, out of tune, sloppy, uncaring.” Savage continues, suggesting:

“All you need to know is that [the bootleg] exists as a document: the Sex Pistols (and Glitterbest) wanted to destroy rock ’n’ roll; at San Francisco the combined forces of ‘rock ’n’ roll’—image, drugs, lack of understanding and the wish to understand—ganged up on the Sex Pistols and destroyed them. As much as they destroyed themselves. Their failure reinforces the status quo and makes that particular battle much harder.”

English music critics, though, have a well-established reputation of eating their own, especially once U.K. bands turned their sights across the Atlantic. In November 1978, the Clash released their second album, Give ‘Em Enough Rope, produced by Sandy Pearlman (responsible for many recordings of classic American metal band Blue Oyster Cult). Savage’s response? “[The Clash] sound as though they’re writing about what they think is expected of them…So do they squander their greatness.”

It’s tempting, of course, to identify events as causal, rather than contingent, when documenting a story with an unhappy ending. For the Pistols, things might have been otherwise. What if Lydon had followed Jones, Cook and McLaren to Rio and, after a few days of sunshine and nights of good sleep, initiated a coup against McLaren? “I regret sayin’ that, that I wanted out,” Jones says. “And I apologized to John that I fucking bailed. We might have continued had we got rid of Malcolm. But that’s just the way I felt, and I just couldn’t get away from my feelings at the time.” (“No Feelings,” huh?) And to think they thereby denied Savage the opportunity to savage their second LP, too.

It’s fitting, perhaps, to have the Pistols disintegrate in Grateful Dead country and, the following year, for the Clash to initiate a long-standing love affair with New York City. The other four horsemen of the a-punk-alypse eventually won battle after battle against the tepid forces of rock ‘n’ roll. In doing so, the Clash affirmed the significance of the Pistols and, most importantly, ensured that when people refer to “‘80s music,” they’re talking about maverick bands like the Clash, rather than Van Halen.