Thurston Moore writes a love letter to New York and his fans in Sonic Life

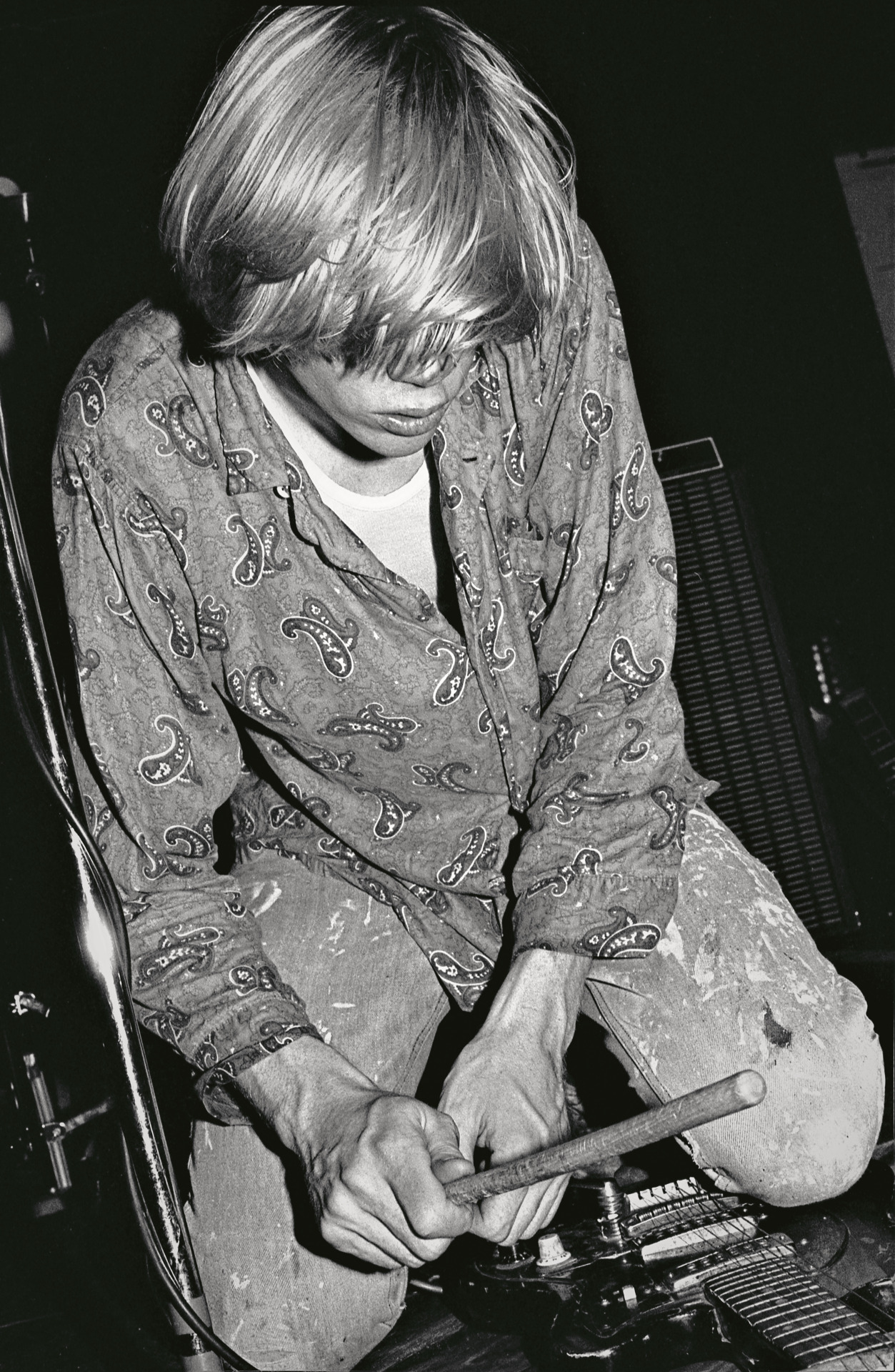

Formed by Thurston Moore in 1981, Sonic Youth were defined by distortion, experimentalism, and innovation. Now in his new memoir, Sonic Life (released Oct. 24), the band’s co-founder, guitarist, and singer chronicles his life beginning with growing up in suburban Connecticut and moving to New York’s East Village.

Moore’s telling begins as a teenager in Connecticut, where he nourished his punk-rock cravings with a steady diet of Iggy Pop and the Stooges, the Ramones, Television, and Patti Smith, his “gateway drug into everything punk rock.” In 1976, when he and his high school friend, Harold, attended the Mumps and Blondie concert at CBGB, he understood his calling — a life in music. This meant moving to a $110 a month apartment on East 13th Street in New York’s Alphabet City. The third-floor walk-up building didn’t have a buzzer system, and his upstairs neighbor was a “barely functional ex-con and drug addict.”

Read more: 20 greatest punk-rock drummers of all time

To make rent, he worked as a foot messenger, a security guard, and a shipping clerk. In 1978, he began playing in a band called Room Tone, which morphed into the Coachmen. Although he was living in squalor, the East Village fueled Moore’s creativity. Spotting Johnny Thunders, Joey Ramone, and Lydia Lunch on the streets “would appear to me like characters out of a Fellini film,” Moore writes.

Moore also describes a dark moment in punk-rock history: After attending a Sid Vicious and his Crew concert at Max’s Kansas City in 1978, Vicious was charged with murdering his girlfriend Nancy Spungen, and months later he died of an overdose. “It was thrilling seeing Sid around the neighborhood and in certain coffee shops where he sat sort of skulking,” Moore says over Zoom from London. “The two of them [Nancy and Sid] did not leave New York alive.”

The narrative continues with Moore’s obsession with music. He writes that the Clash were “a ballistic gamechanger” who revived punk rock, while no-wave bands such as the Contortions, DNA, and Teenage Jesus and the Jerks “were darker, stranger, and dirtier than their punk-inflicted contemporaries… They were the underground to the underground.” Still, Moore loved what they were doing, but “the songs of the Coachmen were built upon basic chords, albeit through the liberating lens of punk rock, as informed by the Velvet Underground.”

In 1979, they played a New Year’s Eve show with Alan Vega of Suicide, one of Moore’s first supporters. “He was a sweetheart of a man,” Moore says. “For him to tell me that he was really into what we were doing at the time was special. His big brother advice about making a record to make it in this business was important at the time. No one had paid attention to me like that.”

1980 was a big year for Moore and the Coachmen, playing Max’s Kansas City — their first and only time. That summer he met Kim Gordon, his longtime bandmate and wife of 27 years. The couple participated in jam sessions, which is when Moore began singing, hoping he was “coming out of the Tom Verlaine, Richard Hell, Joey Ramone, and Lou Reed school.” They played their first show as a trio — Moore, Lee Ranaldo, and Gordon — under the name Sonic Youth at a benefit at Just Above Midtown Gallery in 1981.

Moore’s meticulous research shows in his accounts of every Sonic Youth album, including their self-titled EP in 1982, Confusion is Sex (1983), Bad Moon Rising (1985), and Sister (1987). The band toured domestically and internationally to promote their music, including a gig at CBGB, which was panned by a Village Voice reporter. As a response, Moore wrote a letter to the editor and penned “Kill Yr Idols.”

Moore then moves us through the late ’80s, which includes colorful accounts of domestic and European tours, including shows in Leningrad and Moscow. That includes 1988’s four-sided opus Daydream Nation, which has gone on to reach classic status. “At the time, we were informed by what was happening at SST Records, home of many post-punk, noise-rock bands, including Hüsker Dü and the Minutemen, and both of those bands put out double albums, so we decided to do the same,” Moore says. “We knew we had enough material for a double album, and it was nice that we could let our material blossom … we could let it grow, and we did.”

The momentum continued with 1988’s The Whitey Album. “We originally planned to cover the White Album by the Beatles,” he adds. “We switched gears though and decided to go into the studio with nothing prepared, just ideas informed from what we were listening to at the time, and for us, it was the stripped-down, hardcore beatbox stuff. I was inspired by LL Cool J’s Radio album and the single ‘I Need a Beat,’ which had more to do with rock than disco. We actually used samples from LL Cool J, and we covered Madonna’s ‘Into The Groove.’”

The band, which rotated personnel, continued to work arduously through the ‘90s and 2000s, releasing Dirty (1992) and Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star (1994), in turn gaining national media attention and landing a spot on Late Night With David Letterman. The success continued when Perry Farrell invited them to headline Lollapalooza in 1995. Ever the completist, Moore writes extensively about the band’s final three albums: Sonic Nurse, Rather Ripped, and The Eternal.

Moore beamed when asked about two events — performing with Iggy Pop and Patti Smith. “In 1987, Iggy Pop jumped onstage to play ‘I Wanna Be Your Dog’ with us at London’s Town and Country Club,” he says. “That was a highlight for us. It was absolutely incredible.” He also recounts the moment when Patti Smith invited him to join her for an encore at Central Park in 1996. “I got to know Patti when I interviewed her for BOMB Magazine, but having Patti wave me up onstage and placing Fred 'Sonic' Smith’s guitar on me was awesome,” he adds. “I didn’t have time to think — I just played.”

Ultimately, Moore is a rock historian and a brilliant writer. His poetic sentences evoke New York’s East Village from 1980 through 2000 perfectly. We experience East Village diners and delis, historical music venues, tenement buildings, and railroad apartments. He also writes mellifluously about the commitment required to be in a band. He places us right there with him in vans, planes, and trains to experience a Sonic Youth tour. In Sonic Life, Moore not only tells the story of a burgeoning music scene and an original band, but he also transports us to a time when artists lived their lives on their own terms, just like Sid Vicious and Joey Ramone did.