11 artists from the '70s who formed the frontlines of NYC’s punk scene

Since the world first became aware that there is such a thing as punk, there’s been a nonstop argument about its birthplace. The clueless mainstream media reported for years that it began in England, simply because the Sex Pistols’ snarl was more extreme. Which royally pissed off New York City, the first place to essentially codify what is/isn’t punk. But if you consider the MC5 and the Stooges as history’s first punk bands, wouldn’t its incubator be Detroit?

No. This completely ignores how the Velvet Underground died for our sins in New York City in the mid-’60s.

Read more: 10 glam-rock artists from the 1970s who heralded the coming age of punk

Even before the Stooges or New York Dolls, the Velvets wed Lou Reed’s very nasty, very adult originals about drugs (“Heroin,” “I’m Waiting For The Man”), gender and sexuality (“Candy Says”) or all of the above (“Sister Ray”) to vicious, primitive, feedback-drenched rock ‘n’ roll as filthy and ugly as a New York street corner. As sophisticated as they were primordial, dressed in black leather and wraparound shades as the rest of the world wanted to go to San Francisco and take LSD with flowers in their hair, the Velvets were the counterculture’s photo negative. They were a big middle finger to peace and love, even to proper musical standards (despite John Cale’s classical training).

Is any of this beginning to sound familiar?

Read more: Richard Hell hated his album ‘Destiny Street,’ so he did it three more times

The Velvet Underground recreated rock ‘n’ roll for the East Coast urban environment they inhabited. The Velvets’ music became the sonic signature of ‘70s underground NYC. Which means the story of punk begins with the Velvet Underground in 1965 NYC. The torch got passed first to angry electro duo Suicide and the New York Dolls, then branched into every band playing CBGB and Max’s Kansas City. Here are 11 of New York City’s finest contributions to punk’s canon, many of whom helped create and inform it.

Suicide

Best heard on: Suicide

“People were looking to be entertained,” Suicide singer Alan Vega told The Guardian in 2008. “But I hated the idea of going to a concert in search of fun. Our attitude was, ‘Fuck you, buddy. You’re getting the street right back in your face. And some.’” The delivery system was Martin Rev operating the heavy machinery—a $10 Wurlitzer keyboard groaning through a fuzzbox, with one of the earliest drum machines pulsing away—as Vega assaulted audiences with a heavy chain, whooping and crooning like a radiated Iggy Pop.

They alienated audiences from 1971 on, performing what they called “A Punk Music Mass” on an early flyer, challenging crowds there to see everyone from the Dolls to the Clash. (“I taunted them with, ‘You fuckers have to live through us to get to the main band,’” Vega said of a 1978 Glaswegian Clash audience. “That’s when the axe came towards my head, missing me by a whisker.”) Their self-titled 1977 debut album, the band’s name etched in blood on a stark white sleeve, is one of the best examples of sustained electronic aggression on record. Two-minute blasts like opener “Ghost Rider” (“America, America is killing its youth”) are some of the most menacing music ever made.

New York Dolls

Best heard on: New York Dolls

Unlike frequent billmates Suicide, the New York Dolls came not to destroy rock ‘n’ roll but to celebrate it. Their shows were an eternal celebration of outsiderness, turning being a misfit into something fabulous. Wearing women’s clothes they found in trash cans mixed with black leather, outrageously teased hair and a smear of lipstick and powder found in their girlfriend’s purses, the Dolls blasted a Bronx cheer version of the Rolling Stones through an MC5-esque wall of amps, combining it with the expressive force of girl group records. They elevated amateurism to high art and didn’t give a shit better than anyone. Their first two albums became the worldwide rock ‘n’ roll primer to the first punk generation, alongside the Stooges’ Raw Power. They embodied NYC street rock better than anyone not named the Velvet Underground.

Television

Best heard on: Marquee Moon

Tom Miller and Lester Meyers were boarding school friends who ran away to New York City to become poets. Seeing the Dolls at Mercer Arts Center convinced the duo that rock might be a better delivery system for their French poetes maudits-inspired verse than self-published chapbooks.

Changing their names to Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell, respectively, they slashed their hair creatively, slashed their clothing equally creatively and formed a band initially named the Neon Boys before morphing into Television. Convincing Bowery bar owner Hilly Kristal to let them play on an off-night, they built the stage at CBGB, slowly transforming it into the first dedicated showcase for the coming new sound. Initially playing a raw, garage-y squall that hits contemporary ears as the classic punk template, Verlaine eventually guided the band into a sort of modernist jam band, built around the exquisite lead guitar interplay between him and Richard Lloyd. No longer seeing room for himself in the band he co-founded, Hell left in 1975 for other adventures.

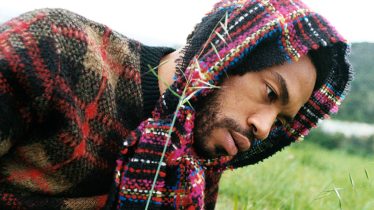

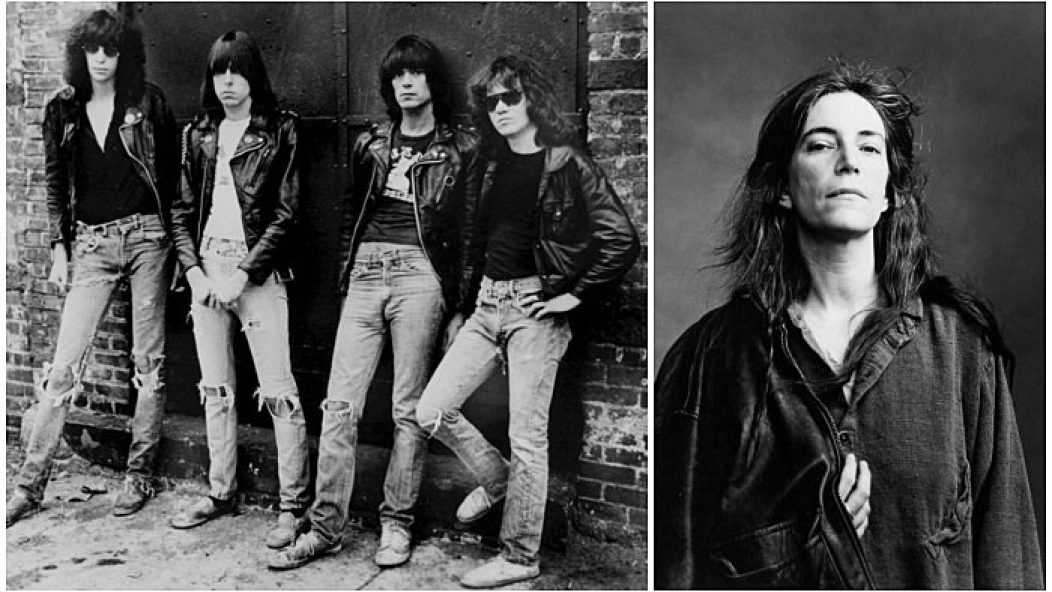

Patti Smith

Best heard on: Horses

A ragamuffin street poet in love with Bob Dylan, Arthur Rimbaud, the Beats and the Stones, Patti Smith first began declaiming her simultaneously mystical and profane verses atop rock critic Lenny Kaye’s electric guitar improvisations in the early ‘70s. By the time CBGB was in full roar as early punk’s home venue, Kaye (now alternating on bass) was part of a full band—drummer Jay Dee Daugherty, keyboardist Richard Sohl and guitarist/bassist Ivan Kral. The minute she asserted “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine” on a dramatically elevated rendition of garage standard “Gloria,” she threw down the gauntlet: Punk could be a poetic cry for freedom, not just three-chord teenage rebel music.

The Dictators

Best heard on: The Dictators Go Girl Crazy!

In many ways, the Dictators are even more the definitive New York punk band than the Ramones. Based around bassist Andy Shernoff’s smart-assed songwriting and the piledriving guitar of Ross “The Boss” Friedman, the Dictators were a more intelligent, more dynamic distillation of power chords, Mad magazine humor and American trash culture: “My favorite part of growing up/Is when I’m sick and throwing up,” read a typical verse in “Master Race Rock.” “It’s the dues you’ve got to pay/For eating burgers every day.” 1975 debut album The Dictators Go Girl Crazy! is as influential a punk record as the first Ramones or Sex Pistols albums.

Ramones

Best heard on: Rocket To Russia

Not to take away a thing from the Ramones. “Blitzkrieg Bop” was definitely the “you can do this too” clarion call heard around the world. They made leather jackets and ripped jeans the standard and brought the Detroit high-energy ideal out to the provinces. They kept instrumentation deceptively simple, though they employed neck-snapping time-signature shifts worthy of any math-rock outfit. The ultimate democratizing gesture from the Ramones: Johnny Ramone’s reduction of the art of rhythm guitar playing to two barre-chord positions played up and down the neck, viciously downstroked through walls of overdriven Marshall amps. The Ramones essentially took lessons from the Dolls and Dictators and made them even more accessible.

Blondie

Best heard on: Eat To The Beat

Blondie began as a not terribly competent revitalization of ‘60s pop and girl group sounds, with a trash aesthetic straight out of the Dolls/Dictators/Ramones playbook—songs such as “Kung Fu Girls” and “The Attack Of The Giant Ants,” anyone? But they had two potent secret weapons: drummer Clem Burke, the Keith Moon of the Lower East Side, and singer Debbie Harry, with a great voice and Marilyn Monroe-esque charisma. First Ramones LP producer Craig Leon squeezed some killer performances from them for their debut LP, including “X Offender,” drenched in Jimmy Destri’s “96 Tears”-like organ. Mike Chapman tightened them further for third LP Parallel Lines, coaxing the mock-disco “Heart Of Glass” out of them. And Blondie became punk’s first worldwide world-beater band.

The Heartbreakers

Best heard on: L.A.M.F.

The New York Dolls’ untutored guitar genius Johnny Thunders and brilliant drummer Jerry Nolan tired of singer David Johansen’s verbal abuse on the road in Florida in 1975. Flying back to NYC, in part to scratch their narcotic itch, they contacted Television’s recently departed bassist Richard Hell, asking him to bring his edgy, poetic songwriting, wired stage presence, quirky vocals and primitivist bass playing to their new band, named the Heartbreakers by fellow ex-Doll Syl Sylvain. Playing one swift gig as a trio, they added gangly guitar foil Walter Lure shortly after, becoming a dressed-down, heavy version of the sound Thunders and Nolan had pioneered in the Dolls. Hell exited after a year, making way for Billy Rath, leaving behind “Chinese Rocks,” a co-write with Dee Dee Ramone detailing opiate addiction.

They went to England in late ‘76 to open the Sex Pistols’ Anarchy tour, staying on to get the record deal American labels denied them. They became an example to English punk bands of just how this music should be played, despite the muffled mastering job on sole studio LP L.A.M.F.

Richard Hell And The Voidoids

Best heard on: Blank Generation

Hell, meanwhile, watched his haircut, wardrobe and nihilistic persona go around the world, with little to show for his pioneering. Tiring of the primitive, garage-ist pounding he’d perfected in Television and the Heartbreakers, he sought to expand punk’s remit, perhaps giving it the free-thinking power of the best jazz. Hooking up with abstract expressionist guitarists Robert Quine and Ivan Julian and future Ramones drummer Marc Bell, Hell and the Voidoids created some of the most powerful and atypical music ever to be dubbed punk on the Blank Generation LP, especially the title track. Here was rock ‘n’ roll reconstructed in a fragmentary, avant fashion, in a manner suggesting a battered art-rock update of the Yardbirds.

Dead Boys

Best heard on: Young, Loud And Snotty

Our last two acts were Cleveland exports looking to take a bite of the Big Apple’s new rock ethic. The Dead Boys were essentially a renaming of ugly glam outfit Frankenstein, who evolved out of protopunks Rocket From The Tombs, taking the more basic Rockets tunes Pere Ubu discarded. Joey Ramone suggested Frankenstein vocalist Stiv Bators take the band to audition for CBGB owner Hilly Kristal. They impressed him with their Stooges-meets-Blue Öyster Cult precision blasts, especially the abnegationist hymn “Sonic Reducer.” Soon, New York thrilled to Cheetah Chrome and Jimmy Zero’s bazooka guitars and Bators’ slapstick Iggy antics and Alice Cooper-ish vocals. Debut Young, Loud And Snotty remains one of punk’s foundational texts.

The Cramps

Best heard on: Off The Bone

Our final Cleveland export to NYC, the Cramps arrived in 1976 to create essentially a New York Dolls more influenced by rockabilly than the Stones, retaining all the garage elements. Lead spectacle Lux Interior howled as he hurled himself at audiences as if his name was Iggy Presley, as lifelong partner Poison Ivy Rorschach oozed ice queen vibes standing stockstill and firing off volleys of reverb-drenched six-string goodness. Meanwhile, the menacing Bryan Gregory ate lit cigarettes and hissed while firing sheets of fuzz from a polka dot Flying V. Future bands fused the Cramps’ self-styled “voodoo rockabilly” with speed-demon hardcore to create psychobilly, while their horror movie obsession got cribbed by everyone from the Misfits to Rob Zombie.