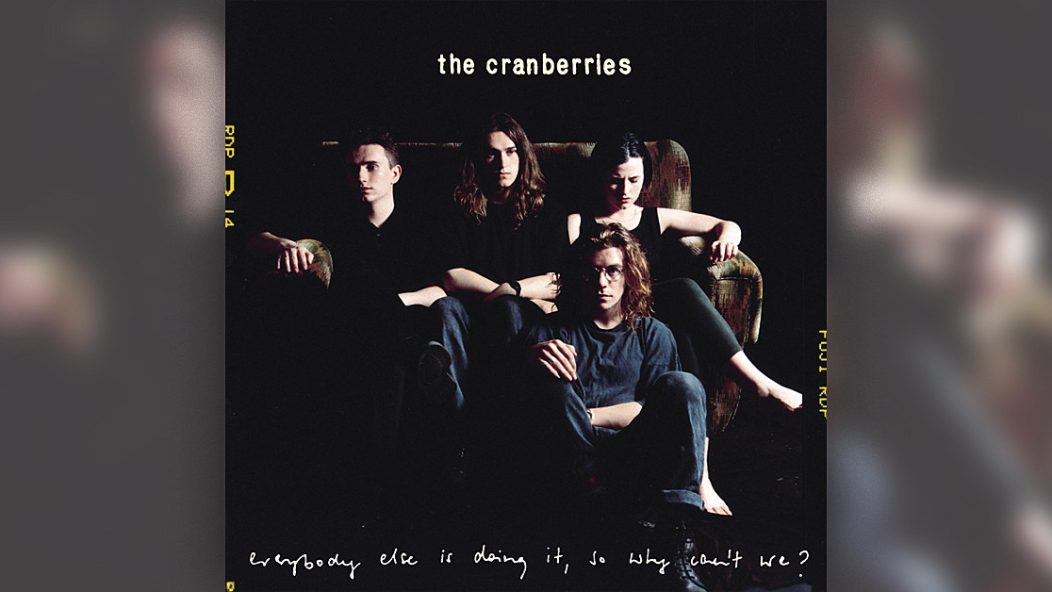

As Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? turns 30, the Cranberries are everywhere

Everything’s coming up 1990s: Rolling Stone is replicating its own Nirvana cover for the year’s most exciting supergroup; the current “indie sleaze” trend is really a re-revival of ’90s aesthetics (as someone who lived through indie sleaze when it was just called hipsterism); and all over social media, everyone’s blasting the Cranberries. Five years after the tragic death of lead singer Dolores O’Riordan at age 46 — and 30 years since the release of their classic debut album, Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? — it couldn’t come at a better time.

O’Riordan, as the story goes, auditioned for the Cranberries in 1990 at the age of 18. The band originally started with guitarist Noel and bassist Mike Hogan, who reportedly met drummer Fergal Lawler breakdancing in a Limerick park. Originally influenced by the Smiths, they worked with a producer who’d collaborated with the band and Morrissey solo for their first album. Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? got flak and disinterest from British music media, but it was a commercial success only bolstered by the release of No Need to Argue in 1994 and its astronomically huge single “Zombie.” (In 2020, the song became one of only a few songs from the ’90s to pass a billion views on YouTube.) Though the band spent the 2000s through O’Riordan’s death in 2018 alternating between breakups and hiatuses, then new music and retrospectives, the world over was shocked by her accidental death.

Read more: 10 iconic alt ’90s movie soundtracks

O’Riordan’s passing was a shock that ignited a wave of reminiscing and celebration, almost universally positive. Music writers like Amanda Petrusich and Una Mullally used the pages of The New York Times and The New Yorker to nominate O’Riordan as a mascot of sorts for the ’90s. Going further and identifying O’Riordan as a specifically Irish icon, Mullally noted that, among other things linking O’Riordan to her roots — for example, the hints of sean nós in her vocal style, a form of storytelling sung in Irish a cappella — it was also about her coolness factor, which she credits with making no shortage of business for Doc Martens in Ireland in the ’90s. Beyond the industry bonafides, people around the world mourned O’Riordan’s sudden death; choirs as far apart as Brooklyn and Russia covered “Zombie” and “Dreams” in homage.

Thirty years after their debut album, it’s not just “Dreams,” which became unavoidable over the last few years — especially since the hit TV series Derry Girls was released on U.S. Netflix in 2018 — or “Linger,” though those two haven’t gone anywhere. In January 2023 for the Irish Times, noticing the same trend, Una Mullally observed, “Good songs are built to last. ‘Dreams’ by The Cranberries is one of those songs. ‘Linger’ [is] coming back too. ‘Zombie; never really went away, particularly in karaoke bars. But Dreams?… It was as if the song itself, released in 1992, was tapping a mic to see if the thing was still on.”

That song’s power extends somewhat past O’Riordan’s own version, though only just: Japanese Breakfast’s immensely popular cover in 2018 for a Spotify session, also a regular live favorite for them, is respectfully referential, allowing the main differences to come across in the unique details of their voices. But we’re far beyond “Dreams.” My For You Page is pleasantly clogged with cheeky, coy dancing to crushing bop “Sunday” (not to mention the range of content loving on “Linger”).

We can attribute the Cranberries’ ubiquity to a few things. First and foremost may be Derry Girls, whose final episodes hit Netflix last fall. The show introduced a new generation to the band’s music, which was a touchstone throughout the series, as well as introducing viewers to the 20th century Irish geopolitical history, which also shaped the band. “Zombie,” one of their biggest hits, was a response to Northern Ireland’s Troubles and its long shadow of violence. This is not to cast a revisionist image of O’Riordan as a radical politico; for one, unlike her contemporary Sinead O’Connor, O’Riordan was devoutly religious — less and less common in Ireland, where the church, though still influential, has lost popularity.

As this essay pointed out, some of the Cranberries’ ubiquitousness across pop culture is due to the capitalist routine that put the band all over movie soundtracks throughout the ’90s, like Clueless and Empire Records. Regardless, Cranberries songs are the soundtracks to so many of our lives, especially when it comes to some of our most nostalgia-tinged youth. O’Riordan was self-conscious of how thoroughly associated her music and lyrics were with rawness, inexperience and emotionality. A 2021 reconsideration of Everybody’s Doing It quotes O’Riordan giving an interview in the ’90s: “The music was so emotional I found that I could only write about personal things….I was sure that it would be considered soppy teenage crap, especially in Limerick, because most bands are really young [men], and their lyrics are humorous or mad. They don’t go pouring their hearts out.”

Alternative music is forever debating how vulnerability and gender interact, and its positives or negatives, in turn insulting or frustrating women musicians who feel reduced to their identity or emotionality (or age, for that matter, given O’Riordan’s youth when the band’s first few albums were released). That same January 2023 retrospective from Mullally troubles that same question, posing that O’Riordan’s “vulnerability” is what makes their early music so enduring. A 2018 retrospective quotes Irish music journalist Dave Fanning telling The New York Times that O’Riordan’s music was less grunge and instead “a soundtrack to [those] growing up between the ages of about 16 and 21… one of the few bands giving them something that was pure pop.” In some sense, that’s fair enough; at least one track off Everybody Else is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? became my parents’ “song” in their early 20s (I’m a few years younger than the album).

But in another sense, it’s oversimplifying and patronizing. So much of the coverage of O’Riordan and of the Cranberries’ oeuvre is dependent on the idea that vulnerability and grunge are somehow oppositional, like feelings can’t be abrasive, like there is an inherent — and derogatory — gendering to ephemeral qualities like sound and affect. O’Riordan paved a path to one of the most exciting tendencies in rock music today, less reliant on “Women In Rock” headlines to see the value and potential beauty in vulnerability. Or maybe what they see as O’Riordan’s vulnerability or youthfulness is really stark plaintiveness, the wisdom to be unhardened, cracked, to the possibilities of the world.

Whatever it was, that cracked-open quality created openings for the same from complete strangers who desperately needed it. In 2012, NPR invited on a listener who recalled a closeted adolescence in an unaccepting religious home and turned to the Cranberries for reprieve. “I remember being overcome with emotion, the emotion that was poured out by Dolores, the lead singer. That touched me — to hear that much passion come out of one body. I really hadn’t heard anything like that before,” Nathan Hotchkiss recalled, saying the music gave him hope.

O’Riordan came onto the radio show with Hotchkiss to thank him. “Everybody in life, you know, we go through struggles. And the reason we go through those struggles is because later, we become stronger people,” O’Riordan told Hotchkiss, who’d shared that he’d grown closer with his parents past their conflict. “Well, life is all about hating, isn’t it? And acceptance. And just to find your own peace in your own heart, and to love yourself, is the most important thing you could do.”

It sounded like something she’d achieved for herself. A year after O’Riordan’s death, the remaining three members released In The End, built from demos they’d been working on with her before her passing. “She'[d] kind of found a way to cope with the mental health thing. That’s why she wanted to write so much. That’s what she kept saying, ‘I have so much to say. I just need the music to put it to,’” Noel Hogan told NPR. The band produced the album in her honor, to honor the progress she’d made and never got to share, honoring all the progress people made with O’Riordan’s voice lighting the way.

Skeptics say the era of Irish cultural greatness is dead and gone, but everywhere you look, it seems there’s yet another renaissance: Sally Rooney beget Paul Mescal, whose sister Nell is a singer-songwriter growing in popularity; with little effort, Banshees of Inisherin induced a Colin Farrell revival; bands like Fontaines D.C. and Inhaler play sold-out shows across the states, and newer acts like M(h)aol are unapologetically political without sacrificing a modicum of rock. And yes, there’s U2; how many of these acts would cite O’Riordan’s powerhouse vocals and sensitivity before the Edge’s (also strongly Irish) riffs? What’s noticeable through all these acts is a willingness to say the hard part out loud, to dive deep into emotions fearlessly — the same tendency that makes people compare Hozier’s yearning love songs to sapphicism.

While I got into the Cranberries’ music before I can even remember — my mom was supposed to see them tour on No Need To Argue while pregnant with me, but says they canceled due to illness — album opener “Ode to My Family” found me belatedly, only a few years ago. “Understand the things I say/Don’t turn away from me,” O’Riordan begins, gently coaxing us towards the bridge: “Do you notice, do you know/Do you see me, do you see me?/Does anyone care?” Witnessing the world as a marginalized person in any capacity right now is enough to beget the question. Does anyone care?

As her contemporary O’Connor once said, it is no sign of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society. For the better, Dolores O’Riordan never got used to it. In life and still now, O’Riordan is a defiant pillar in touch with the world around her, even as it grows ever more tempting to unplug.