How Thomas Dang went from shooting nightlife to directing an Eyedress music video

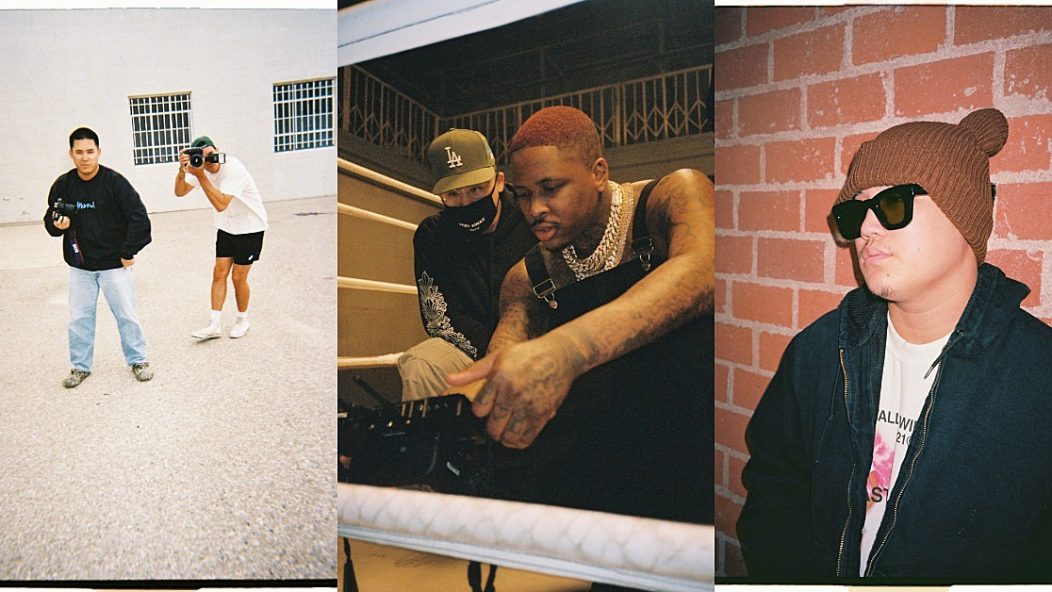

From working with the production company Media Monsters to directing a music video for Eyedress, Thomas “Dangy” Dang has run the gamut of visual media, picking up skills to add to his creative toolbox at each stop along the way. Before he was teaching himself how to navigate the professional sphere to become a successful businessman, he taught himself how to use Photoshop by watching videos on YouTube. At the core of everything he does is a deep love and admiration for music and a work ethic that drives him to do anything but slack, passed down from his parents, who are Vietnamese immigrants.

Read more: For Eyedress, speaking out about mental health is an artist’s greatest responsibility

Where did everything start for you?

I’m Vietnamese, and I am a first-generation-born American. Coming from [Vietnam], my mom and my dad, I never understood where I got the creativity from. I ultimately owe a lot to my parents in terms of them pushing me to work hard and not slack on my end because of how much they set up on their end with their foundation.

[After high school], I landed a [marketing] internship with [Vineyard Vines] in Connecticut for three months. This is when people [were] understanding social media was becoming a big, free way of marketing, and an important one at that. I understood that coming into the internship, but what really attracted me was the creative team and how they worked hand in hand with the marketing team. So that inspired me. When the internship was over, I took all my money, put it into a camera and was like, “All right, I can edit. I know how to Photoshop. Now let me learn how to take the photo, and together, it can be a masterpiece.”

Read more: Jack Kays talks working with Travis Barker on his latest EP—interview

Shooting Rolling Loud back in 2017 was initially my first entrance to the music scene, and it opened doors into where I am now, to working with some of my favorite artists within alternative, hip-hop, indie and R&B. So it’s great to be able to build artists and work and collaborate and have that synergy to work towards a greater common goal, whether it is to have a dope rollout or just dope pieces to make the artist look presentable. The visual presentation is one of the most important things in anything.

So that’s what drives me, whether it’s a music video or a clothing campaign or just a photo shoot. I want to put my best foot forward. At the end, it doesn’t matter how you get there within the creative process because everybody has their own [way]. I think the final image that everybody sees is the most important part.

How long have you been on your own now, working as a creative director and a creative with artists and brands as your own entity?

Probably two years. A production company called Media Monsters brought me to Miami from West Palm Beach. They taught me how to edit videos. I got really fast at it, and I was efficient. Gimbals were becoming a thing, so they gave us gimbals. That introduced me to the nightlife scene in Miami, like club E11EVEN. I was able to meet people, work with a good team. In return, they taught me a lot, allowed me to be in places where I was able to meet other people and network.

[At the] end of November of 2019 was when I left. I was like, “I’m moving back home to West Palm. I don’t know what I’m going to do, but being in Miami, I’m burnt out.” At that point, I didn’t have anything to my name. So I reinvested everything back into getting a camera and going freelance. I had to buy myself the necessities of being able to shoot a decent video with nice gear. I needed the gimbal. I needed the nice camera that can shoot 4K. I needed the monitors and the lenses. I had to reinvest my money back in there because I didn’t really have it when I was at the production company. So I was home in West Palm Beach for a good half a year.

What happens from West Palm? I have huge respect for you because I know a lot of people who have spent a lot of money trying to look successful. What you did was actually a smart business move, to go get your house in order to go to the next level.

West Palm was a reset. I always had this idea to move to L.A. one day. [In] 2020, around July, in the midst of COVID, I moved. I’ve been here ever since. Everyone who’s around me motivates me. They stimulate my creativity. For the first month or so, I was doing little jobs here and there. Then a little bit before August, YG hit me. I met him in Miami back when I was doing the production job at the club, and someone from Rolling Loud that I met on A$AP Rocky’s team, we all connected. So he called me. He was like, “Hey, YG’s in town. You want to spend the day with him?” So I spent the day with YG in Miami, and that’s how I built that connection with him.

What people don’t tell you when you’re the video person and you do something, whether it’s a small club or a big club or a festival, those artists see those videos, and they’re like, “Wow, that guy made me look dope.” So that’s it. I can guarantee you.

YG opened a lot of opportunities for me. I got to work with OhGeesy, help out the rollout for OhGeesy of Shoreline Mafia. Born x Raised, [I] got to work with them. Eyedress, crazy enough, has now become one of my really good friends. I cherish him so much, and it happened through Born x Raised. I ended up doing a cut for them because they did a collab with YG, and they really liked it. They’re like, “We want to put this out.” And I was like, “What track should we use? We’re not going to do just a YG track.”

So 2Tone of Born x Raised was like, “Let’s use an Eyedress track.” My first time ever meeting Eyedress was on set for a music video. I was directing for him. We spoke over the phone once, but he trusted someone that he’d never met to direct a video for him, with a budget. That was the coolest thing ever. Out here, what I’ve realized is people really trust your vision to do things your way. The best feeling for me is [hearing], “I trust your vision. Do whatever you want.”

This interview first appeared in issue #402 (22 for ’22), available here.