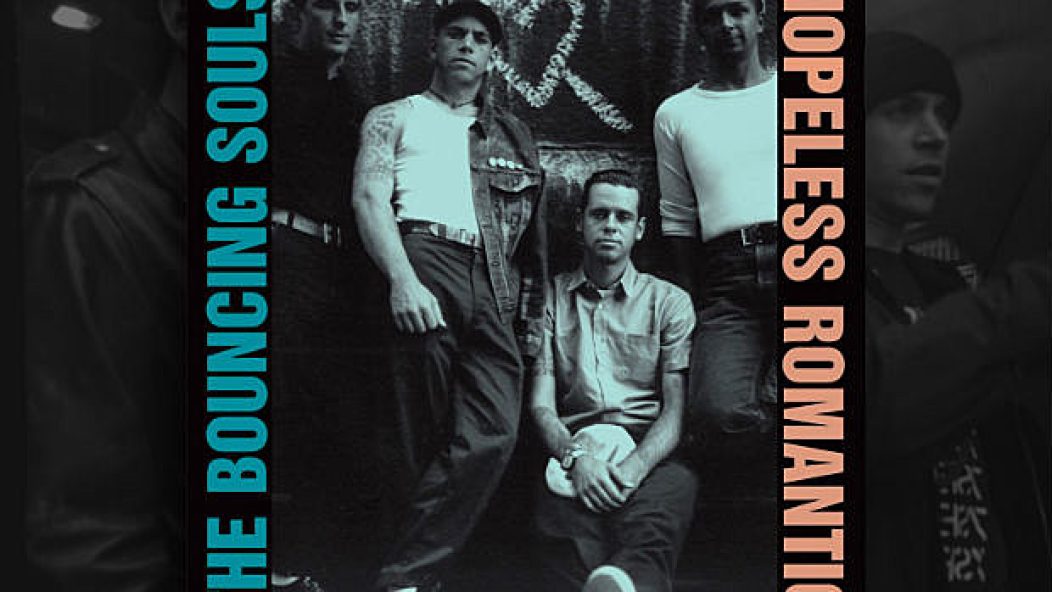

The Bouncing Souls reflect on 15 years of 'Hopeless Romantic'

Summer records. We all have them, right? The ones that always seem to be in your car's CD player when you want to take a drive. The ones that don't even know what an eject button looks like. The ones that contain no real “last” song, even if the track numbers insist on arguing otherwise —each time playback nears a supposed end, our minds crave a return to the beginning, seamlessly making the distance between songs 1 and 13 not nearly as long as numerics would suggest.

They might not have known it at the time, but on May 4, 1999, the Bouncing Souls would release the best summer album they would ever produce, even if it wouldn't end up being the one with the word “summer” in its title. Hopeless Romantic, a 13-track set that helped define the late-’90s version of pop-punk and played a part in keeping Epitaph Records at the top of the indie-label food chain, was ready to launch the Jersey-born quartet from the speakers, straight into the hearts of tens of thousands of punk-rockers near and far. And launch, it did.

“It was our highest selling record to date,” lead singer Greg Attonito says now, reflecting on his band's masterpiece. “I don't know how many we sold, but it's our best-selling, still to this day. Then Napster came out and within another year, CD sales just began to dwindle across the board. People stopped buying them. Hopeless Romantic was kind of like the pinnacle—the last moment of CDs.”

If there's any truth to the statement, an argument could be made that the medium saved one of its best for last. From the opening guitar chords of the title track to the fading backbeat of the closer “The Whole Thing,” to this day the Souls' fourth LP sounds like a band on the verge of taking their biggest leap in both growth and ambition. Backed by the help of pseudo-super-producer Thom Wilson (the Offspring, Face To Face), the set's tone was just gritty enough to avoid compromise, yet accessible enough to turn the heads of holdouts. At the end of the day, the conscious dichotomy of those ideals would combine for a punk blend nothing short of exhilarating.

It began at a rehearsal space in Brooklyn, where Attonito, along with guitarist Pete Steinkopf, bassist Bryan Kienlen, and drummer Shal Khichi, holed up in a room next to a similar space inhabited by the jazz-funk trio Medeski Martin & Wood. The guys spent months riding their bikes to and from the building, writing most of the material that would make up the album only a handful of feet away from the avant-garde group (though by all accounts, they never sat down to chat with one another).

It wasn't until the Souls moved to the famed studio the Record Plant in Hollywood, California, however, that the project began to take shape. They took up residence in a houseboat, sometimes taking breaks by making the short trip up to San Francisco, visiting sights, at one point even exploring the area surrounding Alcatraz. It was an exciting time for the band, a time that brought forth a level of expectation they were never asked to confront before.

“This was the first time we experienced writing music as a relatively popular band,” Attonito explains. “It was a new experience in that way. In the past, we just wrote and we didn't even know if anyone would like it. There was no idea in our minds about what people liked and didn't like.”

Turned out, they were quick learners: Songs such as “Bullying The Jukebox,” “Kid,” and “You're So Rad” quickly became crowd favorites at Souls shows, expanding the circle of followers and admirers seemingly by the spin. Yet even as the bulk of the Hopeless Romantic songs were almost immediately adored by both friends and fans, there continues to be one that haunts the band to this very day.

That track? “Ole!”

Fueled by raucous gang vocals that sports fans around the universe love to use as a call to arms, the group hit a wall when trying to figure out how to craft adequate verses to accompany the surefire hit chorus. Even now, the track is mostly seen as a lark by the guys who wrote it. When asked if there was anything he regrets about the record, for instance, Steinkopf replies with lightning-quick precision, “Oh my God: 'Ole!'” >>>

“It's the worst song we've ever written,” he claims, only half-jokingly. “The chorus obviously is so fun and awesome. It's great that it's become a thing that everyone sings every time we play a show, but I wish we just sang the chorus 100 times in a row; the verses are terrible.”

“For the life of us, we could not come up with a verse,” Attonito adds with a slight laugh. “So, we battled with that in the studio and never really loved it. That's why we ended up, later on, not playing the song for years. Then, because we liked the 'Ole' part so much, we ended up creating this thing live called the 'Ole Fakeout' so we could actually enjoy that part. We were like, ‘Let's make a big, buddies, beer-drinkin' song.’ The lyrics are completely silly. We just went with it. Maybe it could have turned into something else, but why bother? It was just about yelling 'Ole' and being happy.”

It wasn't all bad, of course. Steinkopf maintains that one of his favorite songs in the band's entire catalog is “Night On Earth,” the five-minute nostalgia trip that slices the record in half, both in earnest and with reflection. Meanwhile, Attonito begins to laud “Kid” and “Fight To Live” before catching himself sizing up the tracklisting and exclaiming, “There are some good songs on here!”

Indeed. No matter the good, no matter the bad, no matter the mistakes and no matter the perspective, it's difficult to deny the impact Hopeless Romantic left on the Bouncing Souls. It was their final record with drummer Shal Khichi, and it would also mark the final time the group collaborated with Wilson. By the time 2001's How I Spent My Summer Vacation came around, it was clear the guys felt the dawn of a new era was in full effect.

“It was a crossroads,” Attonito asserts. “It's like this middle. We spent 10 years almost learning everything there is to be about a band: performing, songwriting, recording, translating all that back to performing and then learning it all over again with new songs. We kind of hit the mark with Hopeless Romantic.”

And as for its legacy as one of the premiere summer records in pop-punk history?

“It's one of the ones that people come up and talk about most for me,” Steinkopf says with enthusiasm. “And I think that was the record of the summer for a certain person of a certain age. It's one of the soundtracks of the summer of ’99 for a lot of people, which is cool because I had those kind of records when I was growing up.”

“It was a turning point for the band,” Attonito concludes with his usual blend of affable humility. “It was a landmark. I always feel like that in many ways. It was Shal's last record. It was that time in music history—a hugely pivotal moment in music history as far as how everybody was dealing with the music industry. And it was a level of growth. Looking at the song titles and the way the songs are kind of all very different, they're not just punk songs. There's a cool dynamic to it, lots of ups and downs.

“The imperfections make it perfect,” he adds. “It was a moment in time and that's what recording music and making art is about. It's about a moment. And you put that moment down, and that's the charm in it, too—the imperfections and humanity in it are what make it…” His voice trails off before snapping back from a wistful moment of wonder. “Are what make it good.” ALT