Awsten Knight and Joel Madden have a low tolerance for boredom—watch

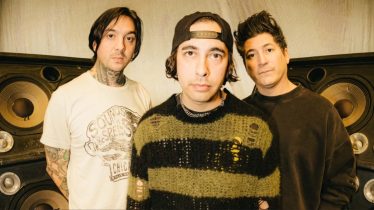

Given Waterparks’ discography, it would have been entirely acceptable and too easy for them to release a true-to-form greatest hits record composed of fan-favorite tracks. But rather than revisiting their previous accomplishments and restyling them, Waterparks’ fourth full-length, Greatest Hits, creates an encapsulating space that analyzes the perception of reality. While the trio wrote and recorded several tracks with Zakk Cervini ahead of the pandemic, which forced mass shutdowns in the music industry, Awsten Knight, Otto Wood and Geoff Wigington utilized their time off from touring to create what can only appropriately be described as their greatest hits.

Read more: Creeper’s Will Gould never expected his Salem side project to be so massive

Spanning an intense 17 tracks, Greatest Hits is more than just another album to have on repeat for the length of the summer. Marking their first release on 300 Entertainment, Knight and co. highlight various peaks and valleys across their careers while also creating a world and storyline that dates back to their inception.

In an exclusive interview with Joel Madden, Knight dives into the freestyle writing process, Waterparks’ new album, comparing music to food and more. You can watch the full interview and read an excerpt below.

What kind of coffee did you get today?

Dude, I went through Aroma. You know the deal.

Aroma is nice.

I think that’s the last place we got breakfast.

It is, like you and me before the pandemic. And during the pandemic, you just made a record, which is great.

Dude, it was crazy because if I didn’t just decide, like, “Oh, now I need to step this up and record a lot more myself,” there probably wouldn’t be an album right now.

That’s crazy, dude. Think about that. If you froze and you were waiting for the tour or waiting for whatever, you wouldn’t have made a record. And you made, I think, your best record yet.

Thank you. That’s the thing when I say it, but maybe people don’t totally believe it. An album will not come out unless I really genuinely think it’s better than the one before it.

Maybe for you guys. Sometimes people think it’s their best record, and it’s not.

But you’ve got to also be self-aware—you have to know. I feel like sometimes there’s a part of people—that’s not saying you’re never going to doubt [yourself] as an artist and shit—but I think people might know deep down if something’s not their best.

I have, for sure. When I was making records, definitely. At least part of me was like, [and] I’m just being honest, part of me was like, “I think we’re supposed to go out and say this is our best record ever.” I felt as an artist when I was promoting records, which I don’t envy, when I see you guys promoting records, I don’t envy. I know it’s hard. But it’s weird. I felt pressure to say this is our best work. And part of me was like, “I love this record. Is it my best record? I don’t know if it’s my best record, but it’s a meal I made, and I want people to try it.”

That makes sense.

Well, let’s say I do a take on Mexican food, right? And so it’s not going to be what you get at your favorite restaurant. But what if I serve it for you and you’re like, “This is pretty good.” If you’re comparing it to my specialty, of course, it’s not going to be. You may go like, “Fuck, I wanted the Italian food that he makes. His take on Italian is really good. His take on this Mexican food, it’s not really what I wanted.” I get it. People are like, “Fuck that.” That’s the thing that fucks us up is I think music is like food. You can try it and go, “Ew, this sucks.”

You’ll see a very, very, very pop-punk dude be like, “This is the shittiest pop-punk band.” Listening to “Snow Globe,” I’m like, “Obviously, this isn’t a pop-punk thing.” I think if people go into something with an expectation, that’s where there’s room to disappoint. But if you go out and you’re like, “Hey, do not expect this. You are not going to be getting this. But I promise you, what you do get is going to be top of the fucking line.”

“And it was my best effort.” Whether my best stuff, according to you, you could be stuck in a certain time because that record meant a lot [to you emotionally]. That’s the other thing: Fans, which is the best part about it, discover your music at different points in their life, and then they hold on to it because it made them feel a certain way. And when you listen to that song from 1997, for me, it takes me right back to that spot where it made me feel better, and it made me feel understood. And now when I listen to it, I still feel that way, but that’s the thing, too, is there’s this whole other side to the emotional experience we had when we listened to your first record or your favorite [record] or whatever it was. I actually think you have even better records in you. I think you’re on your way somewhere. Otto [Wood] and Geoff [Wigington] and you have grown. Think about this. When did we meet?

2015.

I think I flew to Houston.

So we came to L.A. first and met y’all, and then you came out to one of our Houston shows, and it was like [a] 120-cap room. And I remember this other local band that we brought onto the show, they were like, “Hey man, I feel like you know something about this. Why is Joel here?” I was like, “I don’t know, man.” [Laughs.]

[Laughs.] I mean, you know. I remember that show like it was yesterday. And it’s crazy where you guys are at. You guys have grown as a band, as people. It blows me away. I think about that, and I’m like, “OK, this is still the early stages of a band, in my opinion.” You guys are young, and you have that energy. You’re making the records. You’re touring.

Double Dare isn’t even five years old yet. Isn’t that weird? Not even five years old yet.

So that’s what I’m excited about. It’s like the next five years are going to be, to me, full bloom. The band is continuing to just get better in every way, shape and form, from the songwriting, the live show, everything. It just continues to grow. What I still find inspiring is when I find an artist, a painter, a songwriter who will stick with the work until it’s done. They go, “Yeah, it’s not done yet. It’s not done yet.” And I’ll be like, “Sounds done to me.” You’ve played me songs, and I’m like, “That sounds ready to go.”

[Growling voice.] “No, it’s not yet.” I’ll be like, “The program has got to come up. I got to redo that keyboard. I’m going to sing that part. By the way, these vocals are just scratch vocals. It’s like part of it.”

By the way, I think I may have talked to you and Benji [Madden]. I talked to one of y’all at the top of March of last year. I think I was just like, “Hey, how do you write a song? What do you do?” Because I was trying to find new ways. I felt like I was maybe hitting a roadblock, or I was like, not necessarily plateauing or whatever, [but] I was just looking for something new to try, and I was talking to one of y’all, and it was like, “Just go in there and just start singing.”

Yeah, a stream of consciousness is what you call it, which is what we do. We don’t really sit down and try to think about what we’re going to write about. We go in and just flow.

This is the first time I did that on this album. Not all of it, [but] some of it, and it worked really well.

And it’s fun, right?

Yeah, it is because I’m just in there. I loop the instrumental for like 20 minutes. That’s how “Snow Globe” happened, “Fruit Roll Ups” and then pieces of a bunch of other ones. But those two were just full [of] that.

Stream of consciousness.

Yeah. “LIKE IT” was some of that.

Or free form, whatever you want to call it. Freestyle, free form. That’s tight. I love that.

Actually, another thing you told me was how sentences connect.

Once I write a song, I’ll write it down, I’ll type it or whatever and then I’ll read it. If it reads like a book to me, then I feel like it makes sense to me. If I read it like a story, it all connects in some way, shape or form. It’s got to feel like a poem or a story for me to go, “OK, that’s well written.” And then I’ll change some things. But when I write the song, it’s all freestyle until I have enough of a body of a verse chorus that I feel like I’m getting somewhere. By the way, you also know this, [but] I can only work for an hour.

When I start working, I’m just like, “Uhh,” and it’s like seven hours, and then the thing’s done.

Yeah, you grind for eight hours, seven hours. By the way, I think that you have a low tolerance for boredom as well, but I think you’re hyperfocused on your art. I guess you can get tunnel vision. I can’t get tunnel vision. I have way too extreme ADD and ADHD and all that. I think we all have that as artists in different ways, but I think that I struggle to work for more than like an hour-and-a-half on any one thing.

That’s how I feel if I’m working [when] there’s other people in the room. Because then I’m like, “Uhh,” and then there are distractions. And people are like, “What do you think?” But I’m like, “I don’t know.” And then it derails my thing. But if I’m just alone in my apartment, I’ll start something at 11 a.m. or whatever, and then I’ll look and be like, “Oh god, it’s seven. Shit. I guess I should order food,” or like, “Oh, this song sounds amazing, though. It’s basically done.” That kind of thing.

You have something to show for it.

I feel if you wanted to start recording songs just yourself, I think you would maybe be the same way because my brain also can’t stay on more than one thing for long at all. That’s why I have so many things happening at once because I’m like, “I better start. Oh yeah, I’m supposed to do this podcast. OK, let me go do that. Oh, wait, I was going to work on the song. Oh, those designs are due.” But when I actually lock in, it’s one of the few times I can actually focus on something for like a whole day.

Check out the full Waterparks cover story in issue 394, available here.