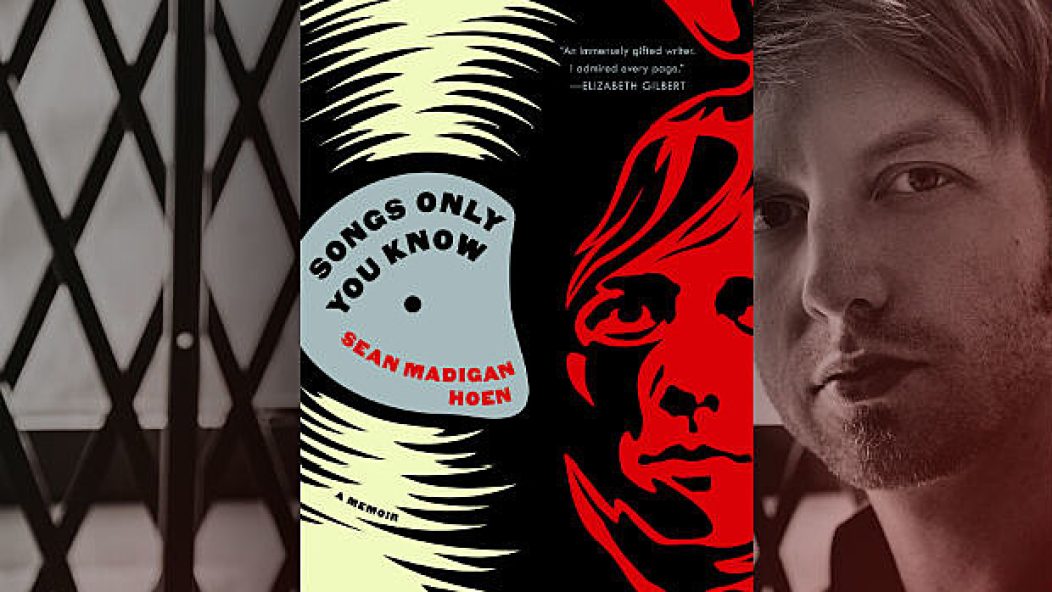

“We were truly in pain, and that still translates”—Thoughts Of Ionesco’s Sean Hoen on his new memoir

Odds are, you’ve never heard of THOUGHTS OF IONESCO. That’s understandable: The Detroit-based three-piece were but a blip on the heavy-music scene’s radar, releasing a handful of abrasive, noisy, sludgy, jazz-influenced metal records that resulted in a few regional tours, a bit of label interest from Relapse Records and plenty of stories from old-school Michigan scenesters who witnessed the musical violence firsthand during the band’s short existence (roughly 1996 to 1999, give or take a few months). There’s a slightly larger chance you remember THE HOLY FIRE, an indie-rock band signed to the Militia Group in the mid-’00s. Both bands were fronted by SEAN MADIGAN HOEN, who has now stepped into the literary arena with his first book, the memoir Songs Only You Know. Eschewing rock ’n’ roll memoir stereotypes, Songs doesn’t glorify sex and drugs, instead exploring the harder parts of romance and addiction. The book opens with a teenage Hoen learning his father, a higher-up at Ford Motor Company, has secretly become addicted to crack, which abruptly and violently pushes his entire family into worlds they never previously imagined. Through the next few hundred pages, the reader is exposed to every inch of Hoen’s struggle with keeping his family together through near-insurmountable circumstances while trying to keep his personal life in some semblance of order and keep his musical flame from being extinguished. It’s a compelling, engrossing read, which is why we chatted with Hoen immediately after finishing the story to learn more.

INTERVIEW: Scott Heisel

When Songs Only You Know first made its way to me, I was excited because as someone who grew up in the Midwest in the late ’90s, Thoughts Of Ionesco were very well known and respected in my local scene. I didn’t read the rest of the book jacket or anything, because I assumed it would be your archetypal “rock memoir.” I definitely wasn’t prepared for where the book took me. It is such an intriguing account of not only the band but your personal life. How much emphasis did you put on purposely not making the book just about the music you created?

SEAN MADIGAN HOEN: I’ve been studying the art of literature and storytelling, going into that wormhole of “What is literary art right now?” So I was really coming at it from a literary perspective. It never really even occurred to me there would be any crossover with music culture; in early drafts of the book, I didn’t even list the name of my band. [Laughs.] There are a lot of rock ’n’ roll memoirs out there, and they are usually written by people who were much better known than anything I did, but I just really wanted it to be a human story, about why would a young man get involved in this [lifestyle], and tell what this world looked like in the late ’90s, which I thought was very interesting material when coupled with my family story. I was compelled to tell my family’s story, but I wouldn’t have done it without all that musical misadventure in there.

One of the things I was really intrigued by were the amount of commonly known details about Thoughts Of Ionesco that are omitted, like that you had Derek Grant, later of Alkaline Trio, play drums for you for a period of time, or that you had a saxophonist in the final incarnation of the band. Are there other elements regarding Ionesco you purposely omitted?

Ionesco were not in any way essential or important to the history of music, but there was a small community of people who definitely were paying attention to it, and we had experiences together. So I really focused on the most meaningful experiences in that time period, whether they were music-related or personal-related. I was really more interested in the characters than the scene. Derek was in an early draft of the book, but then I realized it wasn’t an essential component to the story, as much as I love Derek.

We were really kind of going for the most extreme sound we could come up with in our basement. How far can we take it; how wretched can we make it sound; what’s the most brutal experience we can get to in performance. I really wanted to convey when that style of music is done truthfully, what is behind that, and what kind of people are driven to make that.

It’s funny you talk about your musical motivation, because there’s been that quote that someone from AP wrote 15 or so years ago, describing Thoughts Of Ionesco as “the ultimate realization of pain through sound,” that is still attached to every single press material about the band online. I think that really still holds up, though. Heavy music is in right now, but a lot of these kids—and they are kids—don’t have anything to say. They don’t have actual life experiences to draw upon to make truly emotionally heavy music; they’re just playing downtuned guitars because that’s what they saw Slipknot do 10 years ago. What’s your take on the current heavy-music landscape? I know you moved on musically, but do you still pay attention as a listener?

The funny thing about me and heavy music is it wasn’t necessarily what I was drawn to first. It’s been almost 20 years since Ionesco made our first record, and I’m kind of perplexed that I still get communication about it, like, “Why in the hell are these records we made in the ’90s for $300, how in the hell is anyone still fascinated by this in any way?” We were truly people who were in pain at that time in our lives, and to certain people, that still translates. Some kind of authenticity is what’s always drawn me to all types of music, some kind of fundamental essence in the music that feels pure to me.

As far as heavy music today? I’m not super-tempted to like the new stuff that’s coming out, but Swans are making records again, Godflesh, Jesu, I can still relate to that on ethereal, self-apocalyptic level. [Laughs.] When it feels right, it draws me in. I dig Metz and Young Widows, too.

It’s interesting you mention the idea of authenticity in the music. In the book, when you reach the point where you start the Holy Fire and things start happening for you—you land a manager, you get signed by the Militia Group, you’re opening for big bands—it seems like you lost the authenticity you once had, that you were just doing these things because they were expected of you, and that threw you off the rails again. Tell me about the experience doing the Holy Fire.

Thoughts Of Ionesco broke up on my 22nd birthday, and that’s pretty young for any artist, no matter what your medium is—you’re hopefully still at the beginning at 22 years old. Then my sister passed, and the violence and the rage had no currency for me anymore as an artistic expression. It felt completely false. Playing with those guys, it was so easy; we didn’t talk about songwriting, it just happened. I naively assumed it would be just as easy to start making this beautifully sad, acoustic, spacey music, that it would come naturally—and it didn’t. I spent four years playing these shows that would get booked because I had been in my previous band, and people were just really turned off by me. And I can understand why: I seemed like a chameleon. But after a while, the Holy Fire started to happen.

A bunch of us went to Toronto and recorded songs before we ever played a show, and then it started happening in Detroit. A lot of people started paying attention to us. It was really quite pure at first. But with drinking and drug abuse and the state of trauma I was in, having lost my sister and my dad in pretty brutal ways in such a short amount of time, I was pretty lost. The whole dream of making a sustainable living playing music became my idea of what would fix everything. And really, it became this really unhealthy, toxic obsession. “Oh, if I could just make this happen, it will fix all my problems.” That is when I began writing songs from a place that wasn’t the pure, primal force that I had been connected with in Ionesco.

That period with the Militia Group, I eventually came to feel like I sold out to the extent that I could, and it didn’t feel well to me. Obviously, there are people who sell out in a much greater fashion. [Laughs.] If you actually listen to the Holy Fire’s music, it’s not exactly geared for Top 40. But for me, I had pushed it too far: “What the hell am I doing? This isn’t even good music.” It was a hard thing. You only have your mid-20s once. But yeah, the Holy Fire were this exercise in trying to sell out, trying to see how pop I could make it, as a sort of last-ditch attempt to have a life in music.

Have you said all you need to say musically, or do you still have the desire to make a go of it and start another band? Or are you focused on writing now?

I write every day, and I’m also a sober guy, so that is where I focus a lot of my compulsion—into this daily writing practice. That’s become an inextricable part of my life, and definitely the foremost objective in my life is to really continue following this writing path. But music, I still play quite often. I just really had to separate my experience from my personal dream about it. I’m not talking disreputably about the music dream, the dream that kids have to get out there and have those experiences. But for me, it was really toxic. So it’s kind of been a process to learn how to enjoy making music. Who cares what happens with it? Try to make it as well as you can and as honestly as you can, and not worry about the other stuff, because that’s the stuff that’s going to get me into trouble.

How often do you revisit your old material?

I did pull up some of the Ionesco stuff for sure, and some videos, quite often, but those experiences are all still very close to me. Playing that kind of music, I’ve never felt anything like it. I truly just would be in some other dimension. It’s strange; I hear that 20-year-old kid’s voice on some of those records, and it’s way more powerful than my voice is now. I can’t physically do that anymore. It almost seems like this other thing, this other person I’m hearing.

Even though Thoughts Of Ionesco have been frequently portrayed as dark, brooding and intense, there was humor in your band, which is something I think a lot of people might not have realized. You let this side of Ionesco show a few times throughout Songs Only You Know. Do you ever think you would do a more conventional, “road stories”-type book?

You know, the original draft was 600 or 700 pages, and 85 percent of stuff that was cut was road antics and yarns. Any one of those stories that made the book, I have another 150 of them to choose from. [Laughs.] That was the fun part of writing the book. We did enjoy making the whole trip an adventure. We were trying to work ourselves up into some state, and we were pretty out there. Were someone out there interested in reading it, I could be very easily persuaded to jot those road stories down.

You pull no punches over the course of the story; you expose a lot of flaws of not only yourself but your loved ones. Were you nervous to relive those experiences?

With someone who’s had the post-traumatic experiences like I’ve had, you’re always sort of still living that stuff, so it wasn’t like I had to go and try to remember it—it was all right there, even if it had happened 10 years earlier. In putting it on the page, and going back to those scenes and trying to see them from different angles, that really introduced me to my past in a new way. That’s what I was looking for. It was really hard; it was a pretty rough four years, but I don’t know if I’ve ever grown so much from an artistic pursuit before.

Have you given your mom a copy of the book?

[Laughs.] That’s been the biggest stress of all for me. She’s been through hell, and here I am throwing this thing out to the world, and people we know can get their hands on it if they want. The whole time she’s said, “Do whatever you have to do.” She hasn’t read the whole thing; she’s kind of picked through it, but it was too much, too soon. We’re working together on that.

A large part of the story not only deals with your personal loss but your romantic struggles between two women, Lauren and Angela. I don’t know if those are their real names, but I imagine if either of them were to read the book now, they would learn things about their own situations with you they wouldn’t have known otherwise. Have you shown the book to them?

Those aren’t their real names, but I still care very deeply for both of those women, and feel so much gratitude for how much they were there for me, despite how much of a mess I was. But the character who’s named Lauren in the book, I know she’s read it. What people take from this book, I’m realizing, is not something I have any control over. They’re going to experience things about it I wasn’t able to predict. Lauren was pretty great about it; unfortunately, Angela, who I was most worried about, I’m not able to be in touch with her at the time. But I really tried to approach that aspect of the book from a place of… I didn’t want to bring any of my resentments into the story. That was not the place to air them. The fact is, most of the faults in those relationships were mine, so I erred on the side of putting that up front.

My last question is one that is super-inconsequential to just about everybody, but do you know what happened to that dude Joel Wick, who ran your old label Makoto Recordings? Because he still owes me, like, $60 from that failed 7-inch series he did.

[Laughs.] The funny thing about Joel is I hadn’t heard from him in close to 10 years, and then he got in touch after hearing about this book coming out. He found me through LinkedIn. People still talk about that 7-inch debacle. [In 2001, Makoto Recordings launched a monthly split 7-inch subscription series, advertised as featuring Cursive, Small Brown Bike, Ted Leo, the Good Life, Q And Not U, the Casket Lottery and many more. Only the first four installments ever came out; Makoto closed shortly thereafter, and no one received refunds. —inconsequential scene-politics ed.]

But like a lot of people from that time, myself included, if you went back and asked them about me, they would have a much different impression of who I am. But the thing about being involved in a music scene, especially one as storied as Michigan’s, is that it does really follow you around. When I first moved to New York eight years ago, I was at a party and someone introduced me as “Sean from Thoughts Of Ionesco.” It blew my mind. I was like, “Really? That’s how you identify me?” So those stories follow us around. That was another reason I wanted to write the book—to put those stories out there in as honest a fashion as I can.

Okay, final-final question, which I have to ask: Do you think Thoughts Of Ionesco would ever reunite?

We’ve probably been asked 10 times over the years, but the music we made was borne of such raw pain and aggression and terror, really, that it would be completely ridiculous for me to try and tap back into that. I have really mixed feelings about the reunion phenomenon; I really think some things are better left as a moment in time—Black Flag, for instance. [Laughs.] It’s not gonna be more true now than it was then, so why do it? alt