If Yves Tumor is anything, it’s everything

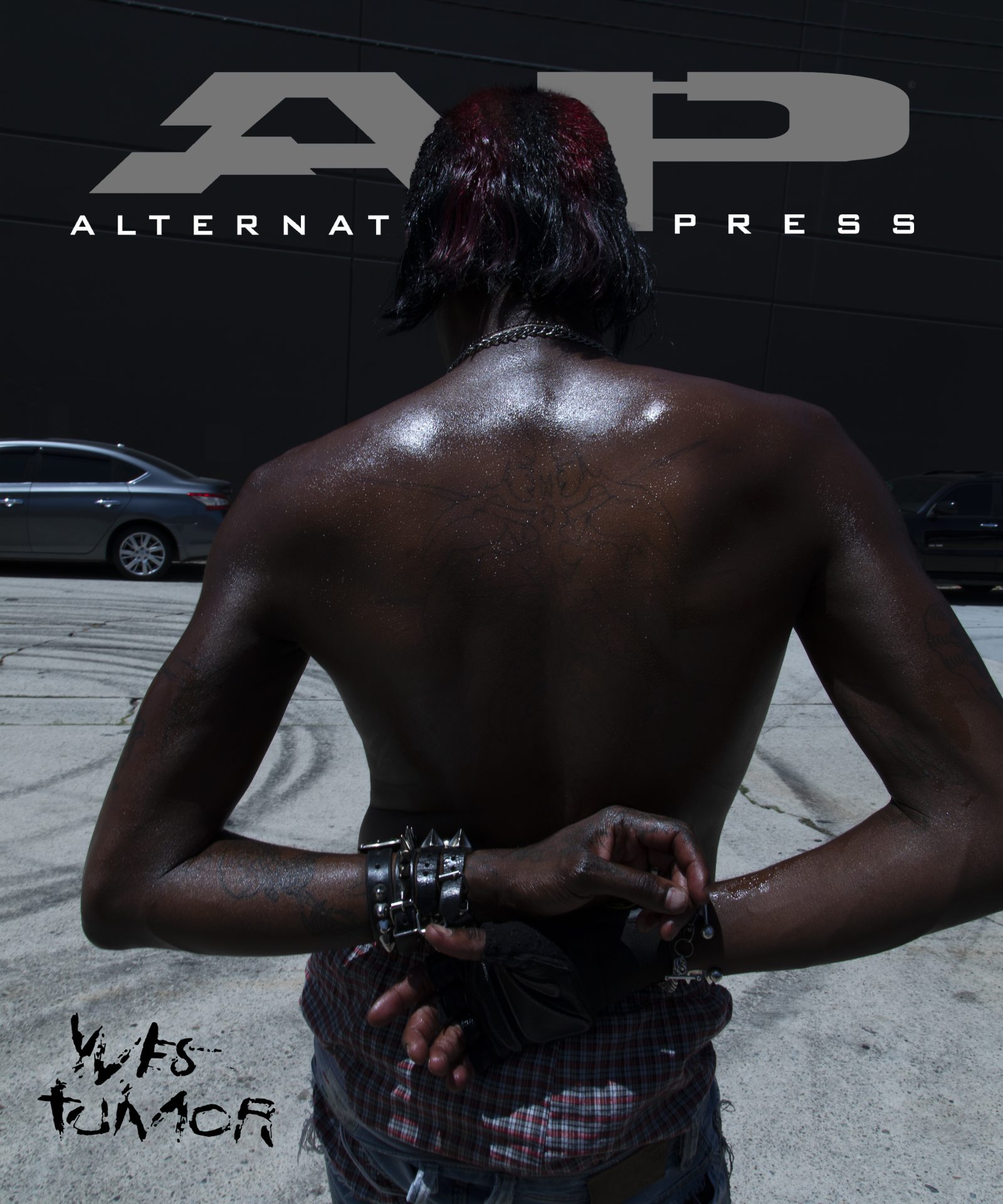

Yves Tumor appears on the cover of the Fall 2023 Issue. Head to the AP Shop to grab a copy.

In an echoey gallery space on Canal Street, midway through a one-on-one rundown of his debut exhibition last summer, a visual artist suddenly stopped to ask me whether I’d heard Yves Tumor’s new album. The question was, of course, somewhat misplaced — a dimming of one’s own limited spotlight to introduce an entirely new character — but also a premise Tumor’s music constantly (1) invites and (2) hinges on: a command of attention, but without ever necessarily having to demand, let alone beg for it, from its own mouth. The musician, who uses they/them pronouns, seldom ever emerges from their shadowy ethos to confirm or deny theory, commentary, or opinion. Every few months on Twitter, one of several recycled Tumor folktales makes its rounds — “NO WAY YVES TUMOR IS 66 YEARS OLD???” a concerned poster might write, inciting a barrage of equally frazzled quote tweets and subreddit questionnaires.

Read more: 25 best albums of 2023 so far

Perhaps it’s believable because, like the mastermind’s work, few reasons exist not to buy into its fantasy. Carried by a virtuosic backing band, Yves Tumor’s music can feel like the glitzy, power-chord-peppered future three stops away on the P-Funk Mothership; at the very same time, it might also feel like the brawny guitar-rock idealism of yesteryear, somewhere along the same phantasmagoria of Rebel Yell and Aladdin Sane. Its life force is that there is no concrete answer to the curiosities it lives to pique, nor will there ever be. Yves Tumor is a myth all of us believe in, and all of us chip into.

Noah Dillon

Typically, contributing to elusive myths can be a frustrating experience — replete with fabricated trail cam footage, conspiratorial language, and friendship-ending arguments — but in this case, it often feels more like the evidence is already there; it’s less a matter of proving it than basking in it. Tumor’s latest LP is Praise a Lord Who Chews but Which Does Not Consume; (Or Simply, Hot Between Worlds), released this past March via the U.K. label Warp Records. On its cover, they’re leaning back on their heels as if to ask Annie if she’s OK, and it feels ever so miraculously like something we cannot see is protecting them from tipping over.

A similar invisible force threads the music between Tumor’s hazy dream sequence and the hypnotized consumers who probe at it through real-world binoculars, hoping to grasp a myth to cling to, or maybe a folktale to regurgitate. On “Heaven Surrounds Us Like a Hood,” an otherworldly love ballad that rides wah-wah pedals into mythic terrain, Tumor serenades an unnamed love interest with supernatural physics-mending: “Well, if you die, it’s OK, you could just restart,” an infantile voice interrupts the opening riff to muse, matter-of-factly. “Yeah, that’s what it is/I met a boy with no head, told me his secrets/I looked into his eyes, you know he was so pure at heart.”

Two of the most intrinsic values to Tumor’s music, as made prominent in monologues like these, are love and rule-breaking — especially when the love itself is what’s breaking the rules. You get the sense that with Tumor, there’s far more emphasis on what must be said than how people may take it. In one of few “interviews” they have ever agreed to, they’re on the phone with Courtney Love, a fellow alt-rock provocateur as eager to stir passion as she is uninterested in granting easy answers. “I honestly don’t really think about how I’m being perceived that much,” Tumor said, at one point. “I just don’t want to ever be in the middle ground of anyone’s thoughts. I’d rather that someone really, really doesn’t fuck with me, or have them drooling.”

As I write this, long-devoted Doja Cat fan pages are shutting down because of similar take-it-or-leave-it sentiments voiced by the pop star on social media. The outburst was not unlike ones that have tested her fanbase in the past: risque comment; initial pushback; brazen double-down; uproar. “I don’t though,” she responded to one fan who asked whether she loved her supporters, “cuz I don’t really know y’all.” As harsh as it is to hear, much of the sentiment is very true. Most artist-to-audience relationships in the era of post-Twitter are parasocial to varying extents.

If you’re a Dean Blunt fan, you’re subjected to an invigorating, never-ending game of fill-in-the-blanks; with a Doja Cat or maybe a Nicki Minaj, you might find yourself harnessing an idea of a relationship you thought was the case, but might one day be shocked to learn is not — like something out of a skit Sabrina Brier would do on navigating tricky friendships with NYC it-girls. The difference between Doja and Tumor is that while one is present for the uproar, the other is largely absent: With no concrete entity to project resentment upon, if you find yourself having a problem with Tumor’s music, it is more likely that you have a problem with yourself.

Noah Dillon

Assuming you do have a problem with yourself, if you’ll allow it to, Tumor’s music thrives on being able to serve as both a diagnosis and a fix. Go ahead and prosecute me, but as is the case for many others, my first taste came to the tune of “Kerosene!” — an early jolt on Heaven To A Tortured Mind, and possibly their most popular song. In that track’s terrain, a serpentine guitar riff snakes beneath Tumor’s equally serpentine vocals, buoying a lovestruck narrative that feels half-desperate and half-deadpanned. “I can be anything,” Tumor promises in its opening line, almost as if transfixed before a swinging pendulum. “Tell me what you need.”

When I first heard it, I had been making similar promises: weeks away from starting my sophomore year of college, and stuck, somewhat, between inventing a version of myself others might appreciate and trying to find the version of myself I did. The crescendo of “Kerosene!” is carried by a frenetic electric guitar outburst, the cathartic implosion of what angsty pressure valve Tumor let simmer for the previous minute or so. “I’ll be your only boy,” Tumor slurs, their voice a murky suggestion in a whirlwind of electricity. “I can be anything you need.” Whether for undergrads deciding which mask they’ll don tomorrow or lovers deciding which soul they’ll love tonight, Tumor’s career-long sentiment sticks: As seems to be the case for the musician, nothing is worth it unless it looks you in your face and tells you it loves you — no matter who doesn’t.

Noah Dillon

Here is a list of confirmed facts about Yves Tumor’s personal life that (kind of?) aren’t up for debate: (1) They were born Sean Bowie (until another biological name comes up) in Florida (God knows when) and (2) They’re currently based in Italy. That’s about it. There are far more unknowns than knowns in their lore, and in some sense, it makes engaging with the music far more about you, the listener, than might be the case for anyone else. You’ll never know what Tumor is thinking, nor what they want you to think; completely removed from context, their songs begin to feel ever so slightly like an all-seeing ghost singing into your soul, privy to secrets you must listen intently to uncover about yourself.

As is the case for any other piece of art that doesn’t arrive with interpretive instructions, Tumor’s music has seen a fair share of labels — none of which are 100% right, and none of which are 100% wrong, either. Among these labels is hypnagogic pop: a dreamlike microgenre fronted by elusive pioneers like James Ferraro and Dean Blunt, and marked by a semi-nostalgic, moving-target sensibility. (As of the writing of this piece, Tumor’s Heaven To A Tortured Mind is rated the No. 1 hypnagogic pop album of all time on Album of the Year, a music site that scores records according to the assessments of several critics. “Whatever you think I am, I’m not: That seems to be the overall message,” one reviewer wrote upon the album’s release.)

Noah Dillon

The category is among many in a sprawling list of early aughts inventions, quoted like scripture by online RYM types, or maybe shamelessly overused — as is the case in this very essay — by music writers running out of adjectives. But in a way, even despite Tumor’s aversion toward categorization and the annoyingness of the genre’s evangelists, “hypnagogic” feels like one of few accuracies in the musician’s whirlpool of myth. The word denotes the lucid, in-between state directly preceding REM sleep: consciousness that both is and isn’t there. If Tumor is anything, as their various streams of consumer consciousness suggest, it’s everything.

And maybe, so are we. Tumor’s music functions best as a psychic mirror, perhaps a portal to versions of ourselves we have yet to meet in real life. On their end of the deal, at least from what we can see, they have long graduated into the infinite existence their work preaches of — definitionless, ageless (deepest apologies to all “NO WAY YVES TUMOR IS 66 YEARS OLD???” tweeters), ceilingless. More and more, listening to Tumor, it feels like the only ingredient to our own infinity — or our understanding of theirs — is being bold enough to believe in it.

The lyrics to “Hasdallen Lights,” a misty deep cut from Heaven To A Tortured Mind, are a lot like the musician’s catalog at large: a series of spiritual questions you may or may not be ready to answer at the moment. “What are you running from?” they sing, slightly above a whisper, in the track’s early moments. “What do you miss? Tell me, what do you crave? How do you feel?” As is often the case, the music functions less as a declarative diagnosis than an open-ended prompt. Its substance hinges on what we do — or don’t do — to finish off its existential alley-oop.

Noah Dillon

Back in that echoey Canal Street gallery space, it seemed that the visual artist was using Tumor’s new album to make me feel better about misinterpreting several of his works in a row. Among the most glaring of these misinterpretations was a portrait he had taken of a silhouetted friend smoking a cigarette — instead of the fading flame it actually was, I had interpreted the red dot hovering over the silhouette’s head as proof that something (or someone) else was getting “smoked.” It was worthy of a laugh then, but to this day, whenever I think about Yves Tumor’s music, I can’t help but see that ominous silhouette against the night sky, its sole indicator of agency — or lack thereof — encased within that dubious red circle.

If Tumor’s body of work takes any shape, it’s likely a circle, anyway: something that can mean both infinity and entrapment; an imprisoning ouroboros that’s also a generative crystal ball. While red is the unofficial hue of passion, it’s also a bit of a circle itself. It oscillates infinitely between the great and the grim — love and rage; blood pumped and blood bled; the mark of an enjoyed smoke or imminent murder. A silhouette, like Tumor’s, is entirely about what is cast onto it. And if Tumor and the visual artist’s shadowy subject have anything in common, it’s that for better or worse, they will never confirm nor deny what we tell ourselves to make them make sense.

Noah Dillon

In an early career Q&A that followed Tumor’s 2016 breakthrough LP, Serpent Music, they were asked by a journalist for their perspective on the world. “We’re doomed,” Tumor said. “That’s it. The world is over. [Laughs.] Sorry to laugh. But I don’t want people to be happy or sad when they listen. I just want them to be hopeful.” In the seven years that have passed since these words were spoken, the world has gotten maybe a tiny bit worse: whether by way of global pandemics, global warming, or global conflict.

Regardless of whether we like it or not, the planet we inhabit is very much the elusive red circle: undoubtedly burning, but with varying fires depending on who you ask — passion, bloodshed, love, hatred. The world has been burning for longer than any of us have witnessed, and it will continue to burn long after we’re done stoking the flames. Yves Tumor makes music for the scarlet days we have left, where larger-than-life forces duke it out for control over our Earth, our imprint, our belief that we may someday live beyond our lives. Tumor wants us to be hopeful, but they will never tell us what exactly there is to be hopeful for. It’s best that we figure it out for ourselves.

Styling by Peri Rosenzweig

Makeup by Holly Sillius

Hair by Fitch Lunar