Sad Summer Festival is growing beyond emo nostalgia

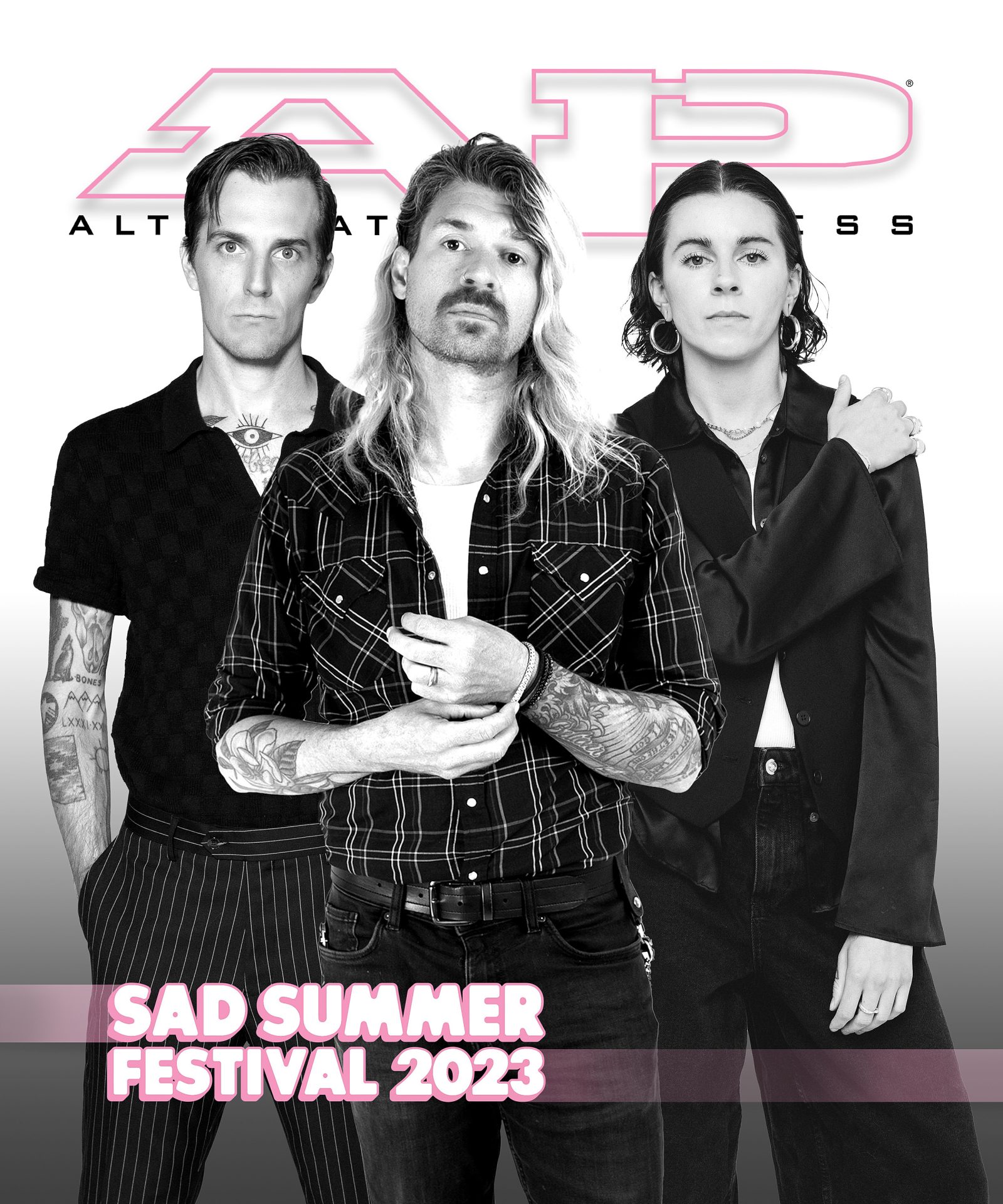

Taking Back Sunday’s Adam Lazzara, the Maine’s John O’Callaghan, and PVRIS appear on the cover of Alternative Press’ 2023 summer issue. Grab a copy here and head to the AP Shop for limited-edition vinyl of PVRIS’ EVERGREEN.

BY THE TIME MEMORIAL DAY ROLLS AROUND, fans of a certain strain of emotionally charged rock music are hardwired for a long day of sunblock, merch runs, concession stand pizza, and an even longer bill of their favorite bands. Chalk it up to three decades under the influence: Warped Tour’s legendary 25-year run laid the foundation, but since 2019, the traveling fest that crowdsurfed its way to the forefront goes by the name of Sad Summer.

If you’re seasoned in contemporary emo and pop punk, you’re likely familiar with Sad Summer Festival and its tongue-in-cheek moniker. If you’ve gone before, there’s a good chance you’ve posed for Instagram in front of something hot pink and black (Sad Summer’s trademark color scheme) while caffeinated mosh-pop riffs permeate the sticky air. And if all this is speaking your language, odds are you’re acquainted with Sad Summer’s 2023 headliners: scene godfathers Taking Back Sunday, all ’round alt-rock good guys the Maine, and electro-rock surrealists PVRIS. While the festival criss-crosses America this July, all three bands are standing on the edge of reinvention, new albums in tow, with miles of unexplored interstate ahead.

Read more: 20 greatest Hopeless Records bands

For now, Adam Lazzara channels a sort of zen restlessness. Chatting from his home in Charlotte, North Carolina, the Taking Back Sunday frontman is eager to engage on Sad Summer and his band’s long-awaited follow-up to 2016’s Tidal Wave, but the many years since his proverbial first rodeo have taught him to dance around the details. He’s scarcely glanced at the tour schedule because he knows his mind’s tendency to tumble down anxious, road-related rabbit holes; he confirms, yes, Taking Back Sunday are in the thick of a new album with pop producer Tushar Apte (whose credits include artists like BTS, BLACKPINK, Demi Lovato and approximately zero rock bands) but won’t go into much sonic detail: “It sounds like Taking Back Sunday because it’s Taking Back Sunday playing it.”

[Photo by Natalie Escobedo]

What gets Lazzara going often involves rock ’n’ roll mythology, and his band’s place within it. References to Bruce Springsteen and Johnny Cash flow freely. “Did you ever see that [Metallica] documentary Some Kind of Monster?” he asks. “Their guitarist Kirk Hammett talks to a psychologist about how they got so big, so quickly, that part of his development froze in that time, at that age. I would never want to be in a position like that. It’s important to me to continue to grow with my talents, as a person. When I’m shoved into this box, it’s taking away from something I’m very proud of.”

The box he’s talking about is emo nostalgia. “To think for one second that all we’re capable of is our first record is a goddamn mistake,” he says. Taking Back Sunday’s feisty 2002 debut album, Tell All Your Friends, helped open the floodgates for a slew of mainstream emo crossovers, including the Long Island-bred band’s own subsequent gold records, 2004’s Where You Want to Be and 2006’s Louder Now. But as the life priorities of OG fans shift from checking tour dates to paying mortgages and finding babysitters, keeping them engaged with new music can be an ongoing challenge. Grown humans using the term “adult emos” is far cringier than anything being sold at Hot Topic in 2004. Alas, Lazzara is a realist. “It’s not lost on me that doing a tour called Sad Summer is not great reinforcement for my words,” he admits.

At first, Taking Back Sunday — Lazzara, guitarist-vocalist John Nolan, bassist Shaun Cooper, and drummer Mark O’Connell — were hesitant to join Sad Summer. Mostly because of the name. Lazzara suggested Rad Summer; organizers thanked him for his creative input, said he was free to call it whatever he wanted from the stage, and Taking Back Sunday signed the dotted line. The fact that the Maine were playing helped, too.

Lazzara hit it off with the Maine the first time he met the Arizona quintet, hanging at the Warner LA offices, circa 2010, when both bands were signed to the label. It wasn’t long before they hit the road together. “You do tours and you’re friendly with everybody, but there’s still a wall up… There wasn’t anything like that with the Maine.” As cost-cutting major labels grew increasingly clueless about what to do with rock bands, both went the indie route — TBS with Hopeless Records, the Maine self-releasing. “From that point on, it was us and our fans against the big, bad industry,” Maine drummer Patrick Kirch recalls. “We got rid of all ideas of, ‘This album has to fit into this type of scene.’”

Survivors of the so-called “neon pop-punk” craze of the late aughts, the Maine ditched their candy-colored deep V-necks and spent the 2010s getting comfortable in their own skin. Beginning with their 2011 LP, Pioneer, they explored many of the same time-tested influences as Lazzara: Tom Petty, Wilco, Pearl Jam. “We’ve done twangy Americana music; we’ve done heavier alt-rock,” frontman John O’Callaghan says. “And we’ve gone as poppy as you could probably go for a band like ours.”

[Photo by Kyle Dehn]

The Maine’s earworm single “Sticky” enjoyed substantial alternative radio play in 2021 and, eight albums into their career, became the band’s first song to crack a Billboard chart. “It’s the same guitar around the entire song, literally,” O’Callaghan says. “With creation, you can sometimes associate [simplicity] with not being up to par. ‘Sticky’ taught us that simplicity sometimes is OK.” A year later, “Loved You a Little,” a tag-team single with Taking Back Sunday and alt-pop singer Charlotte Sands, charted even higher. But as the Maine discuss their forthcoming album, it’s clear they’re not chasing radio play or Spotify streams.

“When you’ve done nine records, it’s hard to not be yourself,” O’Callaghan says. Last winter, the band hunkered down in the Arizona mountains with longtime collaborator, producer Colby Wedgeworth, for work on their not-yet-titled new LP (as of our late-April conversation, they’ve just begun mixing). “When you have as many albums as we do, people ask, ‘Is it like [2015’s] American Candy or more like a Pioneer kind of record?’” Kirch says. “This isn’t a sister album.” O’Callaghan described a set of songs that reflect how the band see themselves in the current moment. “There’s elements of dance, funk guitars on this record… The common theme is, we want energy. We just wanted to be excited. That’s how you convey that it means something to you in a live setting.”

The Maine hope to release new music in time for the start of Sad Summer Festival, which kicks off July 6 in Jacksonville, Florida and runs through July 29 in Irvine, California. Playing before Taking Back Sunday each of the tour’s 16 evenings, the Sad Summer stage will be a familiar one to O’Callaghan and company. After all, they helped build it.

Back in 2019, the Maine founded Sad Summer — the name, the concept, the branding — and for its inaugural run, enlisted friends like Mayday Parade, State Champs, the Wonder Years, Mom Jeans, and Stand Atlantic (the latter two bands return to open all dates this year, along with Michigan rockers Hot Mulligan). Warped’s run as a traveling festival wrapped in 2018, and the Maine eyed a similar model, with some key differences: a less grueling number of shows for artists and fewer tough lineup decisions for fans. “Warped and other festivals, your two favorite bands end up playing at the same time, and you have to miss one,” Kirch says. “The idea was one stage. Let’s partner up these bands that would be doing their own headlining tours and make something bigger than the sum of its parts.”

PVRIS, the third large-print band on 2023’s Sad Summer bill, first hit their stride on Warped Tour in 2015. “It was definitely a this is real moment,” frontwoman Lynn Gunn recalls. As momentum built behind their fierce debut album, White Noise, PVRIS jumped from side stages to the Warped’s main one, but the then-21-year-old Gunn frequently felt disconnected from most of the touring party. “I had a bicycle gang. We would ride to get coffee every day, go find parks, go find fireworks, go anywhere that wasn’t Warped Tour.” From her home in Los Angeles, she speaks with the wisdom allotted from nearly a decade to process that Warped Tour summer.

“I didn’t feel comfortable. I had to shrink myself,” Gunn says. “It was very straight, it was very white and it was very male-dominated… Any time we would try to get a certain press feature and expand outward, because we had done Warped Tour, it almost gave us this weird mark because at the time, everything was coming out about a lot of people’s allegations [regarding incidents related to Warped Tour]. It felt unaligned with my beliefs… It was a big building period for our career, but I would have liked a lot to be better. And I hope Sad Summer can do a little bit better.”

While the live music industry often fumbles inclusion and representation, Gunn’s hope is not lost on the band that founded Sad Summer. “There’s so much that can be improved upon,” O’Callaghan says.

IT’S ALMOST IMPOSSIBLE TO FIND a casual fan of the Maine. Though they’re far from the biggest rock band, Maine fans skew highly passionate and refreshingly positive. Much of this is due to the live experiences the band have curated over the years: 8123 Fest, the bi-annual hometown Phoenix concert they’ve headlined since 2017, and, of course, Sad Summer. “We’ve been trying to create an environment where people become best friends with a person in the crowd they didn’t know before,” Kirch says. As people, the Maine exude devotion and sincerity; over the years, their fanbase — largely women — grew in that image. “They’re coming to a concert because that’s what they do with their friends,” Kirch says. “We’re the background music for their life.”

For PVRIS, Gunn’s own coming-of-age story is almost inseparable from her band’s journey and the following she’s nurtured. At 18 years old, the songwriter-producer came out as gay to her parents by leaving them a letter as she departed her childhood home in Massachusetts for PVRIS’ first tour (her family was quite supportive). As the band grew in popularity, PVRIS events took on their own special meaning. Fans sometimes came out to their own parents, often with Gunn’s help, at concerts and meet-and-greets. Now, almost a decade later, Gunn’s tribe is increasingly at peace. “Our fanbase already felt really communal and free in the sense that people could come to these shows and be themselves. I think the current audience just feels even more expansive and diverse than that origin,” she says.

Creation replaced tension. The band have been live-testing new songs like the fight-or-flight “ANIMAL” and the tranquil “ANYWHERE BUT HERE,” which both appear on their fourth studio album, EVERGREEN (out July 14 via Hopeless Records). “There’s a lot of themes of wanting longevity when everything feels really instantaneous,” Gunn says. “How do you stay true when everything tries to pull you away?”

[Photo by Bridget N. Craig]

EVERGREEN follows 2020’s Use Me, PVRIS’ major-label debut. “We knew signing with a major was a 50/50 chance from the get-go,” Gunn says. “Any artist that goes from an indie label to a major has a really great story or a really bad one.” PVRIS got the latter. “[Warner] were hoping the pandemic would end within a couple months, which is absurd to think about now.” Use Me was pushed back twice across the course of 2020, before finally seeing the light of day that August. It debuted at No. 155 on the Billboard 200 albums chart, over 100 spots lower than 2016’s attention-grabbing All We Know of Heaven, All We Need of Hell. Unfazed, Gunn saw the big picture. “I was ready to make new music. It felt really strange to be promoting an album during [a pandemic]. It didn’t sit well,” she says.

There’s a feral energy to EVERGREEN — the guitars, the beats, the lyrics. If you’ve experienced catharsis in a crowd since live music returned post-2020, you understand. “Now, it’s really important we spend our time intentionally,” O’Callaghan says. “At the shows we’ve played since, there’s an energy you can almost feel, like you could grab it out of the air and put it in your pocket,” Lazzara says.

“Going to shows before I was in [the Maine],” O’Callaghan remembers, “those were places I felt I could be more myself than anywhere else.”

At Sad Summer Festival, that’s the goal. Whether unveiling new music, experimenting with pop collaborators, or navigating the latest fluctuation in the term “emo,” these artists have all learned what it means to step outside themselves, to build their own communities. And thrive within them.

“Let’s keep growing together. Let’s fuckin’ see what’s out there,” Lazzara swaggers in his Carolina-Long Island hybrid accent. “It’s a big ol’ world, and there’s lots of wild shit to get into. You’re not going to be able to get into the wild shit if you’re not ready for it.”

He pauses. “And how are you going to get ready for it? You’ve got to grow.”