The Lead: Don’t drop the SOPA: Musicians weigh in on the controversial legislation

Have you ever listened to your favorite songs on YouTube? Uploaded a random picture of a cute, fluffy kitten to your Facebook account? Tweeted a link to an MP3 you didn’t write or record? Left a comment with a link to an illegal album download on a forum? If the answer to any of these is yes, a set of laws Congress recently considered could alter the way you find—and consume—music and all other forms of media online.

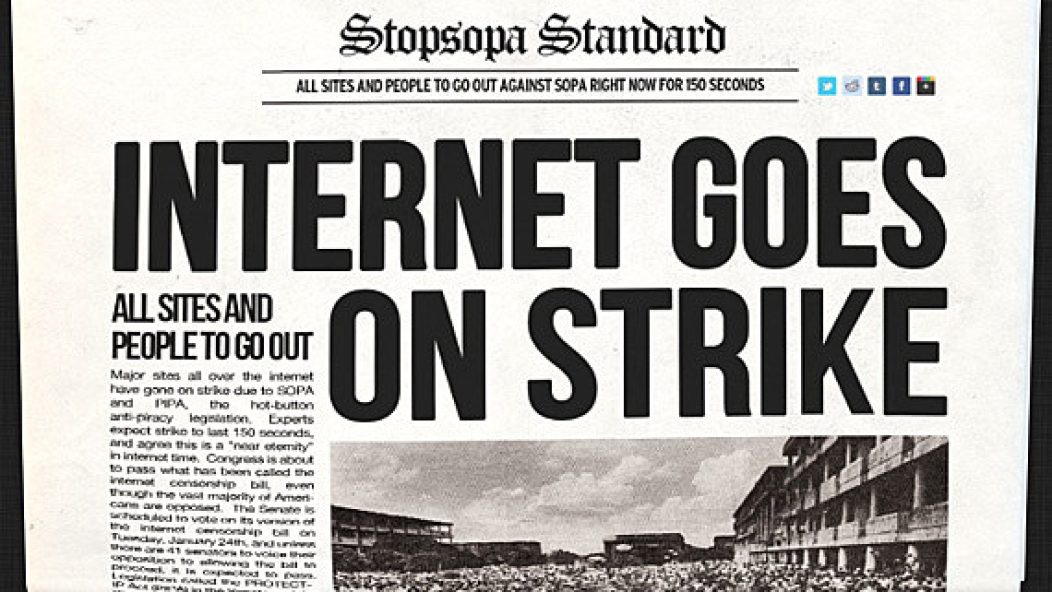

The Protect-IP Act (PIPA) and Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) are two pieces of anti-piracy legislation recently deliberated on by the Senate and House of Representatives, respectively. After backlash in the form of Internet protests including support from high-profile websites such as Wikipedia and Tumblr, both bills have been put on hold for the time being. Don't breathe easy just yet, however: Less than a week before this current ‘shelving,’ SOPA was originally ‘shelved,’ only to come back within a few days, and postponement doesn’t mean the bill is dead or going away—Congress will wait it out and then try again.

Still, it's smart to be aware of what the legislation entails. What these bills could do is give the federal government and copyright holders the power to take action against websites accused of containing protected content; they also change who is responsible for finding and removing infringing content. The bills are almost exactly alike; the only difference is that SOPA has a provision that makes unauthorized streaming content illegal.

Right now, here’s how things work: If infringing material is uploaded to a website, it’s the responsibility of the copyright owner to contact the website and request it be taken down. If the host doesn’t remove the offending content, they face punitive action. For example, if a YouTube channel has songs on it that the account owner doesn’t own—that means any band who’s covered, say, Adele, and uploaded it to their channel—whoever owns the copyright of the song must contact YouTube to inform them of the infringing content, and then YouTube removes it.

If SOPA were to pass, this process will be reversed: The site that hosts the content will immediately be held responsible for infringing material. The responsible site can be immediately cut off from doing business with advertisers such as Google AdWords or payment processors such as PayPal (the main source of revenue for many websites). Following our previous example, if the same songs were uploaded to YouTube with SOPA in effect, and YouTube didn’t catch them before the copyright holder did, YouTube could be immediately cut off from possible advertising revenue without due process for hosting—or even just allegedly hosting—pirated content. A copyright holder can suspect infringement, and they can order the takedown of a site until it’s cleared.

This is just one example of how these laws could affect high-profile websites. Any website which contains user-submitted content—Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Reddit, Wikipedia—could be forced to monitor their content closely to make sure pirated material isn’t being posted. For a simple explanation of the way SOPA and PIPA work, watch this video.

Copyright law and the use (and misuse) of intellectual property heavily affect the music industry, of course. A musician’s livelihood depends on how they make money in relationship to their art, so SOPA and PIPA have direct effects on the future of the music industry. The opinions on the way the legislation should be handled vary greatly. Buddy Nielsen, Senses Fail frontman and label manager of Mightier Than Sword, finds comfort in SOPA and thinks it will help rejuvenate the music industry. “I think [SOPA’s] great,” he says. “I think that we’re going to get to a point very soon where everything is on the Internet. [Without legislation like SOPA,] you’re going to put entire businesses out of business because there won’t be any money in [music]—an industry based on people’s intellectual property.”

Nielsen says his biggest problem is that “people have devalued music” and that this is causing the business aspect of music to die. He hopes SOPA will help change that and bring sales back to the music industry. “You can sign up for Spotify for $10 per month and get almost every record in the entire world,” he says. “Amazon sells records for 89 cents. You, in turn, teach an entire generation of kids there is no value in music—that it’s not worth paying for. As a place for business, it is then extinct.

“If you can’t get to the free music, you’re not going to download it,” he continues. “I don’t buy into the idea that music isn’t selling because it’s not good now. I think music isn’t selling because it’s so easy to steal it.”

On the opposite side of the coin is Circa Survive guitarist Colin Frangicetto. Admitting that as a proprietor of intellectual property, he understands it may be confusing to be against a bill built to protect his artistic output, he still calls SOPA “a Trojan Horse. It’s a way to give the establishment more control over user-generated content sites,” he says. “The people fighting for this bill obviously say that’s ridiculous, but the main people who have been giving money to the representatives of this bill are in the entertainment industry. It basically comes down to money. It comes down to the fact that these representatives really don’t understand what this bill could do to freedom of speech on the Internet as well as innovation and jobs.”

Using Senator Patrick Leahy (D-VT) as an example, Frangicetto points out the role money plays in this legislation. The politician has “supported gay rights, women’s rights and criticized the Patriot Act,” but is for PIPA, according to Frangicetto. “It’s strange and perplexing [that Leahy supports PIPA] until you look at his campaign and the people who contribute the highest,” he says, citing Time Warner and Walt Disney Co. as two examples of generous campaign donors. “Anyone that thinks our political system isn’t bought and paid for by lobbyists, then they should just look at that. Why would this person who has fought for all these other things then turn around and support a bill like this that could so obviously damage the freedoms and infrastructure of our economy in a lot of ways? It’s right there in the writing: it’s money.”

Beyond giving more control to the powers-that-be, Frangicetto also touches on the importance of social media, which could potentially be crippled under SOPA, and how the vague language of the bills could take down just about any site. “When you look at the Occupy movement or any large-scale descent/protest kind of movement, they’ve been vastly more successful over the last few years because of social networking and because of sites that are unfiltered and uncontrolled,” he says. “If it got to a place where they were able to take down a site just because it had a link to some album download, you could basically use that as an excuse to take down any site—and that’s where it starts to get really hairy.”

While the two-party system tends to bleed into how we view issues—only having two options for how to view a law—things aren’t so black and white. Rob Sheridan, a visual artist most notable for his extensive work with Nine Inch Nails, sees an old regime trying to cling to their archaic business models. “The first route [to fix piracy] needs to be adapting business models to adjust to the Internet,” he says. “The most effective way to stop piracy is simply in providing better services. You have the entertainment industry now run by lawyers and accountants and CEOs, and not by people who are forward-thinking. They only want to protect the way that they do business now.”

History seems to agree with Sheridan, as well. “If you look back historically, they fought the same battle against VCRs and cable TV and cassette tapes and CD burners,” he points out. “They’ve fought every single technology that’s come along that they thought could damage their business at the time.” Going all the way back to the introduction of recorded music, Sheridan points out that musicians who were freaked out over the phonograph’s invention are reacting in the same way artists who aren’t adapting to internet culture are freaking out today: “How are we going to make money now?” The way they made money at the time was based on live performance, so with the introduction of recorded music, who would go see live performances for musicians to make money? “We all know how that turned out—the business transformed and they made a lot more money selling records,” he says.

Throughout his time working with Reznor and Nine Inch Nails, Sheridan has been a part of one of the most innovative business approaches to music. Prior to the release of several of their records, fans have had the opportunity to listen to them in their entirety—2005’s With Teeth hosted 13 different listening parties across America, and 2008’s Ghosts I-IV and The Slip were both released for free online before any physical distribution. “Our albums don't leak. Why? Because we don't send them to anyone until we release them online. This allows us to control our release and make the most of its impact.”

“It’s the shortsightedness that frustrates me,” Sheridan adds. “There are too many examples out there of people whose works are being pirated and are succeeding because they’re flexible enough to come up with new business models and engage their audience. The old media industries aren’t flexible enough to do that and they aren’t interested in doing that.”

Finding a balance between fighting piracy and allowing innovation is no easy task, especially for legislators. But with the help of the industries SOPA and PIPA affects, along with the consumers, a consensus can come. Support has waxed and waned for the bill; web host Go Daddy changed its stance after pressure from internet communities, and 13 Congressmen dropped their support for PIPA after the January 18 internet blackout protests. Some aspects of the law, including domain black listing have even been pulled before it reaches a vote. The bills bring up tumultuous and convoluted issues affecting a large number of people—including music consumers.

After these January 18 Internet protests—which included a blackout of Wikipedia, Reddit and countless other sites raising awareness about the laws and their potential effects if passed—pressure is on lawmakers and industry leaders everywhere to find compromise in the near future. No matter which way you feel, it’s important to make your voice heard before the bills come up for vote. Find contact information for your representatives right here. “These congressmen barely even know how to use the Internet,” Sheridan says. “They’re not going to stop. They’re just going to keep going at this.” Do not be silent—let the voice of a tech-oriented youth’s voice be heard.